Recently I had one of those incidents of intellectual synchronicity that happen to me from time to time. I had grudgingly, after years of resistance, set up a Twitter account (I still won’t do Facebook). For whatever reason Twitter reminded me of a book I had read eons ago by the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard called The Present Age. I decided to dig the book out from the catacombs of my dusty attic to find out what my memory was hinting at. More on that synchronicity I mentioned later.

The Present Age is Kierkegaard’s 1846 attempt to think through the spiritual and existential consequences of the new condition of a cheap and ubiquitous press. The industrial revolution wasn’t only about the accelerated production of goods, but also enabled the mass production of information. The art of printing was ripe for a revolution having remained essentially unchanged since Guttenberg in the 1400s.

In 1814 the Times of London acquired a printing press with a speed of 1,100 impressions per minute. The widespread adoption of this technology gave rise to extremely cheap publications, the so-called, “penny press”, that were affordable for almost anyone who could read. The revolution in printing lit a fire under the mass literacy that had started with Guttenberg extending the printed word downward to embrace even the poorest segments of society and was facilitated by the spread of public education throughout the West.

This revolution had given rise to “the public” the idea of a near universal audience of readers. While some authors, such as Charles Dickens, used this 19th century printing revolution to aim at universal appeal Søren Kierkegaard really wasn’t after a best seller status giving his works such catchy titles as Fear and Trembling.

What Kierkegaard is for can be neatly summed up in one quote from The Present Age:

If you are capable of being a man, then danger and the harsh judgment of reality will help you to become one. (37)

Kierkegaard wanted individuals to make choices. Such choices came with very real and often severe ethical consequences that the individual was responsible for, and that could not be dismissed. The ethical life meant a life of commitments which were by their very nature hard for the individual to fulfill.

One of the main problems Kierkegaard saw with the new public that had been generated by the cheap press was that it turned everyone into a mere spectator.

The public is a concept that could not have occurred in antiquity because the people en masse, in corpore, took part in any situation which arose, and were responsible for the actions of the individual, and moreover, the individual was personally present and had to submit at once to the applause or disapproval for his decision. Only when the sense of association in society is no longer strong enough to give life to concrete realities is the Press able to create that abstraction ‘the public’, consisting of unreal individuals who never are and can never be united in an actual situation or organization- and yet are held together as a whole” (60).

The issue for Kierkegaard here is that, since the rise of the press, the world had become enveloped in this kind of sphere of knowledge which had become disconnected from our life as ethical and political beings. A reader had the illusion of being a participant in, say, some distant revolution, famine, or disaster, but it was just that, an illusion. Given how much this world commanded our ethical and political attention, when in reality we could do nothing about it, Kierkegaard thought people were likely to become ethically paralyzed in terms of those issues where we really could, and should, take individual responsibility.

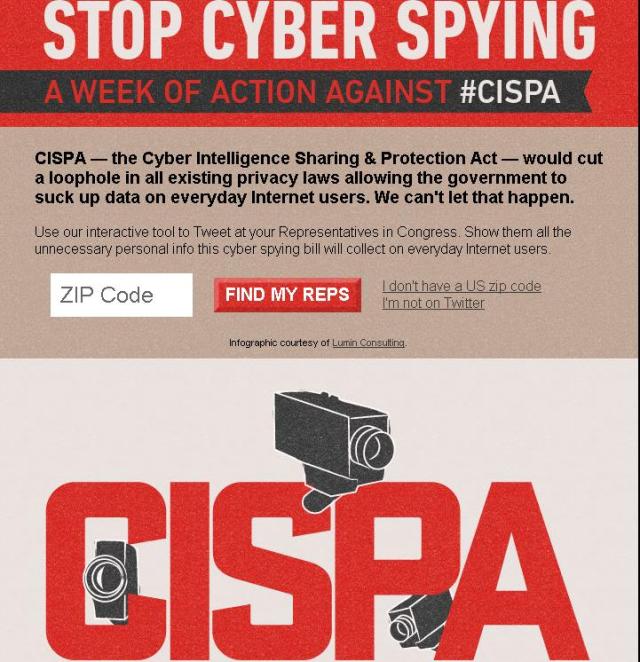

And now back to that synchronicity I had mentioned. Right around the same time I had dug up my dusty copy of The Present Age I was walking through the local library and happened to pass a 2011 book by Evgeny Morozov called The Net Delusion. On a whim I brought the book home and when I cracked it open to my surprise saw that he had a chapter dedicated to the Danish philosopher- Why Kierkegaard Hates Slacktivism. Morozov’s point was that the internet gives us this illusion of participation and action that requires very little on our part. We sign this or that petition or make this or that donation and walk away thinking that we have really done something. Real change, on the other hand, probably requires much more Kierkegaard-like levels of commitment. These are the types of commitments that demand things like the loss of our career, our personal life, and in the case of challenging dictatorships, perhaps the loss life itself. The ease of “doing something” offered by the internet, Morozov thought might have a real corrosive effect on these kinds of necessary sacrifices.

It is here that synchronicity plot thickens, for both Kierkegaard and Morozov, despite their brilliance, miss almost identical political events that are right in front of them. As Walter Kaufmann in the introduction of my old copy of The Present Age points out Kierkegaard totally misses the coming Revolutions of 1848 that were to occur two years after his book came out.

The Revolutions of 1848 were a series of revolts that ricocheted across the world challenging almost every European aristocracy with the demand for greater democratic and social rights. Rather than having acted as a force suppressing the desire for change, the new press allowed revolution to go viral with one revolt sparking another and then another all responding to local conditions, but also a reflecting a common demand for freedom and social security. Individuals acting in such revolutions were certainly taking on very real existential risks as states cracked down violently on the revolts.

Similarly, Morozov’s Net Delusion, published just before the beginning of the 2011 Arab Spring, missed a global revolution that, whatever the impact of new technologies such as Twitter, were certainly facilitated rather than negatively impacted by such technologies. The Arab revolutions which spread like wild-fire inspired similar protests in the West such as the Occupy Wall Street Movement that seemed to require more than just pressing the “like button” on Facebook for the committed individuals that were engaged in the various occupations.

When it came to the Revolutions of 1848, Kierkegaard was probably proven to be right in the end as the revolutions failed to be sustained in the face of conservative opposition paving the way for even more revolutionary upheaval in Europe in the next century. Only time will tell if a similar fate awaits the revolutions of 2011 with conservative forces regrouping in autocratic societies to stem any real change, and Western youth becoming exhausted by the deep ethical commitments required to achieve anything more than superficial change.

- Søren Kierkegaard, The Present Age , Translated by Alexander Dru, Introduction Walter Kaufmann, Harper Torchbooks, 1962

- Evgeny Morozov, The Net Delusion, Public Affairs, 2011