“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

William Faulkner

Dystopias, just like utopias, are never unmoored from a society’s history. Our worst historical experiences inevitably become the source code for our nightmares regarding the future. Thankfully, America has been blessed with a shallow well from which to feed its dystopian imagination, at least when one compares its history to other societies’ sorrows.

After all, what do we have to compare with the devastation of China during the Taiping Rebellion, Japanese invasion, or Great Leap Forward? What in our experience compares to the pain inflicted on the Soviet Union’s peoples during World War II, the factional bloodletting of Europe during the wars of religion or world wars? Only Japan has had the tragic privilege of being terrorized into surrender by having its citizens incinerated into atomic dust, and we were the ones who did it.

Of course, the natural rejoinder here is that I’m looking at American history distorted through the funhouse lens of my own identity as a straight- white- male. From the perspective of Native Americans, African Americans, women, and sexual minorities it’s not only that the dark depths of American history were just as bad or worse than those of other societies, it’s that the times when the utopian imagination managed to burst into history are exceedingly difficult to find if indeed they ever existed at all.

Civil war threatens to inflict a society not only over the question of defining the future, but over the issue of defining the past. Deep divisions occur when what one segment of society takes to be its ideal another defines as its nightmare. Much of the current political conflict in the US can be seen in this light- dueling ideas of history which are equally about how we define desirable and undesirable futures.

Technology, along with cultural balkanization and relative economic abundance, has turned engagement with history into a choice. With the facts and furniture (stuff) of the past so easily accessible we can make any era of history we chose intimately close. We can also chose to ignore history entirely and use the attention we might have devoted to it with a passion for other realities- even wholly fictional ones.

In reality, devoting all of one’s time to trying to recapture life in the past, or ignoring the past in total and devoting one’s attention to one or more fictional worlds, tend to become one and the same. A past experienced as the present is little more real than a completely fictionalized world. Historical re-enactors can aim for authenticity, but then so can fans of Star Trek. And the fact remains that both those who would like to be living in the 24th century or those who would prefer to domicile in the 19th, or the 1950’s, by these very desires and how they go about them, reveal the reality that they’re sadly stuck in the early 21st.

What we lose by turning history into a consumer fetish that can either be embraced or pushed aside for other ways to spend our money and attention isn’t so much the past’s facts and furniture, which are for the first time universally accessible, but its meaning and meaning is not something we can avoid.

We can never either truly ignore or return to the past because that past is deeply embedded in every moment of our present while at the same time being irreversibly mixed up with everything that happened between our own time and whatever era of history we wish to inhabit or avoid.

This strange sort of occlusion of the history where the past is simultaneously irretrievably distant in that it cannot be experienced as it truly was and yet is also intimately close- forming the very structure out of which the present is built- means we need other, more imaginative, ways to deal with the past. Above all, a way in which the past can be brought out of its occlusion, its ghosts that live in the present and might still haunt our future made visible, its ever present meaning made clear.

Ben Winters’ novel Underground Airlines does just this. By imagining a present day America in which the Civil War never happened and slavery still exists he not only manages to give us an emotional demonstration of the fact that the legacy of slavery is very much still with us, he also succeeds in warning us how that tragic history might become more, rather than less, part of our future.

The protagonist of Underground Airlines is a man named Victor. A bounty hunter in the American states outside of the “hard four” where slavery has remained at the core of the economy, he is a man with incredible skills of detection and disguise. His job is to hunt runaway slaves.

The character reminded me a little of Dr. Moriarty , or better, Sherlock Holmes- minus the cartoonishness. (More on why the latter in a second) But for me what made Victor so amazing a character wasn’t his skills or charm but his depth. You see Victor isn’t just a bounty hunter chasing down men and women trying to escape hellish conditions, he’s an escaped slave himself.

A black man who can only retain what little freedom he has by hunting down human beings just like himself. It’s not so much Victor’s seemingly inevitable redemption from villain to hero that made Underground Airlines so gripping, but Winters’ skill in making me think this redemption might just not happen. That and the fact that the world he depicted in the novel wasn’t just believable, but uncomfortably so.

Underground Airlines puts the reader inside a world of 21st century slavery where our moral superiority over the past, our assumption that we are far too enlightened to allow such a morally abhorrent order to exist, that had we lived in the 19th century we’d have certainly stood on the righteous side of the abolitionists and not been lulled to sleep by indifference or self-interest crumbles.

The novel depicts a thoroughly modern form of slavery, where those indignant over the institution’s existence do so largely through boycotts and virtue signaling all the while the constitution itself (which had been amended to forever legalize slavery in the early 19th century) permits the evil itself, and the evil that supports it like the human hunting done by Victor, to continue to destroy the humanity of those who live under it.

Winters also imagines a world like our own in that pop-culture exists in this strange morally ambiguous space. Victor comforts himself by listening to the rhythms of Michael Jackson (a brilliant choice given the real life Jackson’s uncomfortable relationship with his own race), just as whites in our actual existing world can simultaneously adopt and admire black culture while ignoring the systematic oppression that culture has emerged to salve. It’s a point that has recently been made a million times more powerfully than I ever could.

The fictional premise found in Underground Airlines, that the US could have kept slavery while at the same time clung to the constitution and the Union isn’t as absurd as it appears at first blush. Back in the early aughts the constitutional scholar Mark Graber had written a whole book on that very subject: Dred Scott and the Problem of Constitutional Evil . Graber’s disturbing point was that not only was slavery constitutionally justifiable but its had been built into the very system devised by the founders, thus it was Lincoln and the abolitionists who were engaged in a whole scale reinterpretation of what the republic meant.

No doubt scarred by the then current failure of building democracy abroad in Iraq, Graber argued that the wise, constitutionally valid, course for 19th century politicians would have been to leave slavery intact in the name of constitutional continuity and social stability. He seems to assume that slavery as a system was somehow sustainable and that the constitution itself is in some way above the citizens who are the source of its legitimacy. And Graber makes this claim even when he knows that under modern conditions basing a political system on the brutal oppression of a large minority is a recipe for a state of permanent fragility and constant crises of legitimacy often fueled by the intervention of external enemies- which is the real lesson he should have taken from American intervention abroad.

In Underground Airlines we see the world that Graber’s 19th century compromisers might have spawned. It’s a world without John Brown like revolutionaries in which slave owners run corporate campuses and are at pains to present themselves as somehow humane. What rebellion does occur comes in the context of the underground airlines itself, a network, like its real historical analog that attempts to smuggle freed slaves out of the country. Victor himself had tried to escape more than once, but he is manacled in a particularly 21st century way, a tracking chip embedded deep under his skin- like a dog.

What Winters has managed to do by placing slavery in our own historical context is recover for us what it meant. The meaning of our history of slavery is that we should never allow material prosperity to be bought at the price of dehumanizing oppression. That it’s a system based as much on human indifference and cravenness as it is on our capacity for cruelty. It’s a meaning we’ve yet to learn.

This is not a lesson we can afford to forget for, despite appearances, it’s not entirely clear that we have eternally escaped it. It seems quite possible that we have entered an era when the issue of a narrow prosperity bought by widespread oppression come to dominate national and global politics. To see that- contra Steven Pinker– we haven’t escaped oppression as the basis of material abundance, but merely skillfully removed it from the sight of those lucky enough to be born in societies and classes where affluence is taken for granted, one need only look at the history of cotton itself.

Sven Beckert in his Empire of Cotton: A Global History skillfully laid out the stages in which the last of the triad of great human needs of food, shelter and clothing was at last secured, so that today it is hard for many of us to imagine how difficult it once was just to keep ourselves adequately clothed to the point where the problem has become one of having so much clothing we can’t find any place to put it.

The conquest of this need started with actual conquest. The war capitalism waged by states and their proxies starting with the Age of Exploration succeeded in monopolizing markets and eventually enslave untold numbers of African to cultivate cotton in the Americas whose lands had been cleared of inhabitants by disease and genocide. The British especially succeeded not only in monopolizing foreign trade in cotton and in enslaving and resettling Africans in the American south, they had also, at home, managed through enclosure to turn their peasantry into a mass of homeless proletarians who could be forced through necessity and vagrancy laws into factories to spin cloth using the new machines of the industrial revolution. It was a development that would turn the British from the most successfully middleman in the lucrative Asian cotton trade into the world’s key producer of cotton goods, a move that would devastate the farmers of Asia who relied on cotton as a means to buffer their precarious incomes.

The success of the abolitionists movement, and especially the Union victory in the US Civil War seemed to have permanently severed the relationship between capitalism and slavery, yet smart capitalists had already figured out that gig was up. Wage labor had inherent advantages over slave based production. Under a wage based system labor was no longer linked to one owner but was free floating, thus able to rapidly respond to the ceaseless expansion followed by collapse that seemed to be the normal condition of an industrial economy. Producers no longer needed to worry about how they would extract value from their laborers when faced with falling demand, or worry about their loss of value and unsellabilty should they become in incurably sick or injured. They could simply shed them and let the market or charity deal with such refuse. Capitalists also knew the days of slavery were numbered in light of successful slave revolts, especially the one in Haiti. The coercive apparatus slavery required was becoming prohibitively expensive.

It took capitalism less than twenty years after the end of American slavery to hit upon a solution to the problem of how to run commodity agriculture without slavery. That solution was to turn farmers themselves into proletarians. The Jim Crow laws that rose up in the former Confederate states after the failure of Reconstruction to turn the country into a true republic (based on civic rather than ethnic nationalism) were in essence a racially based form of proletarianization.

It was a model that Beckert points out was soon copied globally. First by Western imperialists, and later by strong states established along Western lines, peasants were coerced into specializing in commodity crops such as cotton and forced to rely on far flung markets for their survival. In the late 19th century the initial effect of this was a series of devastating famines, which with technological improvements, and the maturation of the market and global supply chains have thankfully become increasingly rare.

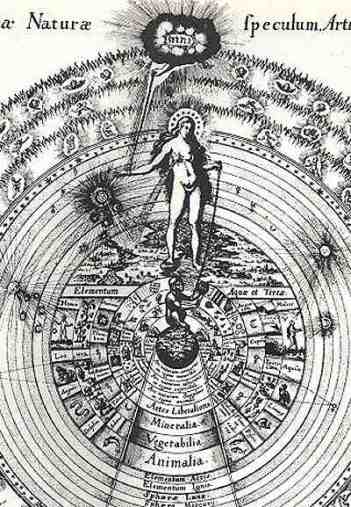

What Beckert’s work definitely shows is that the idea of “the market” arising spontaneously on its own between individuals free of the interfering hand of the state is mere fiction. Capitalism of both the commercial and industrial varieties required strong states to establish itself and were essential to creating the kind of choice architecture that compelled individuals to accept their social reality.

Yet this history wasn’t all bad, for the very same strength of the state that had been used to establish markets could be turned around and used to contain and humanize them. It required strong states to enact emancipation and workers rights rights (even if the later was achieved under conditions of racialized democracy) and it was the state at the height of its strength after the World Wars that finally put an end to Jim Crow.

But by the beginning of the 21st century the state had lost much of this strength. The old danger of basing the material prosperity of some on the oppression of others remained very much alive and well. Beckert charts this change for the realm of cotton production with the major players in our age of globalization being no longer producers but retail giants such as WalMart or Amazon- distributors of finished products which aren’t so much traditional stores as vast logistical networks able to navigate and dominate opaque global supply chains.

In an odd way, perhaps the end of the Cold War did not so much signal the victory of capitalism over state communism as the birth of a rather monstrous hybrid of the two with massive capitalist entities tapping into equally massive pools of socialized production whether that be Chinese factories, Uzbek plantations, or enormous state subsidized farms in the US. Despite its undeniable contribution to global material prosperity this is also a system where the benefits largely flow in one direction and the costs in another.

It’s as if the primary tool of the age somehow ends up defining the shape of its political economy. Our primary tool is the computer, a machine whose use comes with its own logic and cost. To quote Jaron Lanier in Who Owns the Future?:

Computation is the demarcation of a little part of the universe, called a computer, which is engineered to be very well understood and controllable, so that it closely approximates a deterministic, non-entropic process. But in order for a computer to run, the surrounding parts of the universe must take on the waste heat, the randomness. You can create a local shield against entropy, but your neighbors will always pay for it. (143)

Under this logic the middle and upper classes in advanced economies, where they have been prohibited from unloading their waste and pollution on their own weak and impoverished populations have merely moved to spewing their entropy abroad or upon the non-human world- offloading their waste, pollution and the social costs of production to the developing world.

Still, such a system isn’t slavery which has its own peculiar brutalities. Unbeknownst to many slavery still exists, indeed, according to some estimates, there are more slaves now than there have ever been in human history. It is a scourge we should increasingly work to eradicate, yet it is in no way at the core of our economy as it was during the Roman Empire or 19th century.

That doesn’t mean, however, that slavery could never return to its former prominence. Such a dark future would depend on certain near universal assumptions about our technological future failing to come to pass. Namely, that Moore’s Law will not have a near term successor and thus that the predicted revolution in AI and robotics now expected fails to arrive this century. The failure of such a technological revolution might then intersect with current trends that are all too apparent. The frightening thing is that such a return to slavery in a high-tech form (though we wouldn’t call it that) would not require any sorts of technological breakthroughs at all.

In Underground Airlines what keeps Victor from escaping his fate is the tracking chip implanted deep under his skin. There’s already some use and a lot of discussion about using non- removable GPS tracking devices to keep tabs on former convicts no longer behind bars.

The reasoning behind this initially seems to provide a humane alternative to the system of mass incarceration we have today. The current system is in large measure a white, rural jobs program – with upwards of 70 percent of prisons built between 1970 – 2000 constructed in rural areas. It was a system built on the disproportionate incarceration of African Americans who make up less than 13 percent of the US population, but comprise 40 percent of its prisoners.

The election of Donald Trump has for now nixed the nascent movement towards reforming this barbaric system, a movement which has some strangely conservative supporters most notably the notorious Koch Brothers. What their presence signals is that we are in danger of replacing one inhumane system with an alternative with dangers of its own. One where people we once imprisoned are now virtually caged and might even be sold out for labor in exchange for state “support”.

This could happen if we enter another AI winter and human labor proves, temporarily at least, unreplaceable by robots, and at the same time we continue down the path of racialized politics. In these conditions immigrants might be treated in a similar way. A roving labor force used to meet shortages on the condition that they can be constantly tracked, sold out Uber-like, and deported at will. Such a “solution” to European, North American, and East Asian societies would be a way for racialized, demographically declining societies to avoid multi-cultural change while clinging to their standard of living. One need only look at how migrant labor works today in a seemingly liberal poster child such as Dubai or how Filipino servants are used by Israelis who keep their Palestinian neighbors in a state of semi-apartheid to get glimpses of this.

We might enter such a world almost unawares our anxieties misdirected by what turn out to be false science-fiction based nightmares of jobless futures and Skynet. Let’s do our best to avoid it.