In a recent interview the ever insightful and expansive Vernor Vinge laid out his thoughts on possibility and the future. Vinge, of course, is the man who helped invent the idea of the Singularity, the concept that we are in an era of ever accelerating change, whose future, beyond a certain point,- we cannot see. For me, the interesting thing in the Vinge interview is just how important a role he thinks imagination plays in pulling us forward into new technological and social possibilities. For Vinge, our very ability to imagine some new technological or social reality signals our ability to create it in the near future. Imagination and capability are tied at the hip.

One of his own examples should be sufficient to explain. It was a lack of imagination, not so much technological as social, which prevented the ancients from seeing Hero’s steam engine as something better than an amusing toy. “For what,” an ancient anchored to the past of what had seemingly always been “ could be a more productive and efficient a system than slavery?”

The ancients were tied to the short chain of the past, we have a very different orientation to time- our gaze is forward not backward. In part, the accelerating rate of technological change today emerges out of this change in our imaginative orientation away from the past and towards the future. Many of us are both thinking about the future seriously, and have a broadened perspective on what is possible because we have learned how to dream. We are, in Vinge’s words “grabbing the fabric of reality and pulling it towards us” a great change in the attitude towards the future than could be found a mere 500 years ago.

Vinge is right about this, the idea of imagining the future as something fundamentally different from the past is a relatively recent human habit of mind. If the future was a painting one might say that for most of human history the painting remained monotonously the same with the new only added very slowly to it. To continue with this analogy, what one started to see beginning around the late 1200s was the appearance of blank space on an expanded canvas to which the new could be added, something that would eventually happen at an accelerating pace.

And it has been the kinds of imagination we associate with Vinge’s craft -science-fiction- that has played a large role in producing despite Ecclesiastes “new things under the sun”. Science-fiction, its progenitors and its derivatives were one of the main vectors by which the new could be imagined. We merely had to await the improvement in our technical skill, our ability to “paint” them- to bring them into being. Here is one of the first and maybe the most powerful example. Way back in the late 1200s Roger Bacon in his Epistola de Secretis Operibus Artis et Naturae Magiae predicted the future with an accuracy that would make Nostradamus blush. Predicting:

Machines for navigation can be made without rowers so that the largest ships on rivers or seas will be moved by a single man in charge with greater velocity than if it were full of men. Also cars can be made so that without animals they will move with unbelievable rapidity… Also flying machines can be constructed so that a man sits in the midst of a machine revolving some engine by which artificial wings are made to flap like a bird… Also a machine can easily be made for walking in the seas and rivers, even to the bottom without danger.” (Aladdin’s Lamp 417-418)

Now, Roger Bacon seems to disprove part of Vinge’s ideas regarding imagination and the future, namely; the idea that if we can dream of something we are likely to make it happen right away, for it would take another seven centuries for us to be driving in cars or flying in airplanes. Yet this gap would disappear, in fact it would be measured in decades rather than centuries, for almost all of the history of science-fiction, up until recently that is. But I am getting ahead of myself.

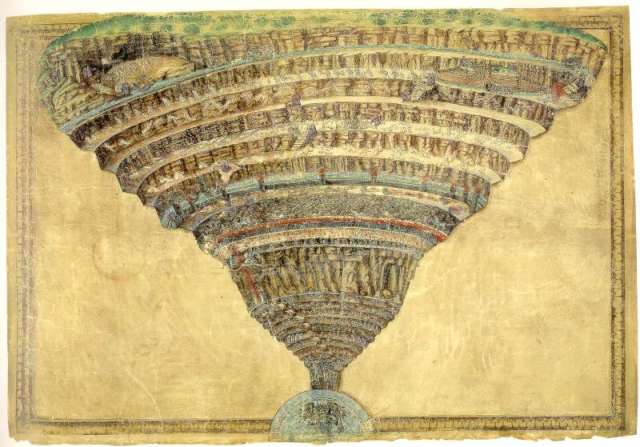

Leonardo Da Vinci also still belongs to the age when the ability to imagine ran far out in front of our capacity to create in the real world. Da Vinci in imagining flying machines or submarines or tanks- such as the speculative inventions pictured above- might be said to be practicing an early type of science- fiction, expanding the realm of what was imaginable and therefore potentially possible, but like the possibilities sketched out in Bacon they would take a long time in coming.

Related to this expansion in imaginative possibilities that began in early modern Europe that same region also experienced an expansion of the world itself. During the Age of Exploration Europeans came face-to-face with the true size of the world, but it would be sometime before they knew the details about the human societies that inhabited it. This was a recipe for the imagination to run wild and provided an arena of fantasy in which European anxieties and hopes could be played out. One got all sorts of frightening stories about “cannibals”, but one also had Utopian lands presented as ideal cities rediscovered. These stories allowed Europeans to imagine alternatives to their own societies. After the discovery in the same period that the moon and planets were also “earth-like” worlds you get the birth of that staple of science-fiction- intelligent life on other planets- with works such as Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle’s Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds that allowed brave writers to explore alternative versions of their societies in yet another landscape.

By the 1800s the gap between what we dreamed and what we could do was closing incredibly fast. Not only was the world being transformed by industrialization it was also clear that technology was steadily improving and thus revolutionizing and expanding the prospects for human societies in the future – we now call this progress. Our canvas was being filled in, but was also being even further stretched out to allow for yet more possibilities. Science-fiction writers were to play a large role in driving this expansion both of what we could do and what, because it was imaginable was deemed possible.

To name just a few of these visionaries: even if predicting the future of technology wasn’t his intention, Jules Verne expanded our technological horizon by dreaming up trips to the moon and undersea voyages. Then there was the cultural sensation of Edward Bellamy and the incomparable H.G. Wells.

Bellamy, in his futuristic Looking Backward 2000-1887 was just one of many who thought the new landscape of human flourishing would be found through the proper organization of the enormous powers of industrialization. Bellamy got a number of things right about the future, from department stores and credits cards to a version of the radio and the telephone that lay less than a century into the future.

H.G. Wells was even better, his trope of a time machine in lieu of a Rip-Van Winkle type sleep to get one of his protagonists into the future notwithstanding, he got some pretty important, though sadly dark, things from atomic bombs to aerial warfare essentially correct. Less than half a century after Wells had imagined his nightmare technologies they were actually killing people.

For a time the solar system itself, not because it contained living worlds resembling the earth as Fontenelle had imagined, but because it was at last reachable seemed to hold the hope of yet another canvas upon which different versions of the future could be drawn. The absolute master in presenting the sheer enormity of this canvas was Olaf Stapledon who in works like Last and First Men and Star Maker placed humanity’s emigration into space within the context of the history of life on earth and even the universe itself giving such a quest what can only be called a religious dimension.

Stapledon was thinking in terms of billions of years, but the technologies to take us into space spurred forward by the Second World War- Nazi V rockets, and then the Cold War “space race” seemed to be bringing his dreams into reality almost overnight.

This was the perfect atmosphere not only for pulp science-fiction and comics based around the exploration and settlement of space, but for much deeper fare such as that of Stapledon’s great heir, Arthur C. Clarke, who wrote his own religious versions of the meaning of the space race.

Yet, it was our future in space where the narrowing gap between what we can dream and what we could do began to not only stop narrowing but actually to widen. Clarke was eerily on the money when it came to the development of telecommunications and the personal computer, but wide off the mark when it came to our immediate future in space. His 1968 novel and movie 2001: A Space Odyssey has us taking manned missions to Jupiter in that millennial year which, sadly, has come and gone without even having men return to the moon. Despite his hopes, his beautiful fiction did not inspire the creation of actual space ships twirling space stations and missions, but a whole series of big budget films and television series based in outer space. More on that in a minute.

Right around the time American astronauts were setting foot on the moon science-fiction was taking some other and ultimately introspective turns more aligned with the spirit of the times. In the words of the man Fredric Jameson in his Archaeologies of the Future called the “Shakespeare of science-fiction”, Philip K. Dick:

Our flight must be not only to the stars but into the nature of our own beings. Because it is not merely where we go, to Alpha Centaurus or Betelgeuse, but what we are as we make our pilgrimages there. Our natures will be going there, too. “Ad astra” — but “per hominem.” And we must never lose sight of that. (The Android and The Human)

It would be a while until we’d make it to Alpha Centaurus or Betelgeuse, for humanity’s rabbit leap movement into the solar system sputtered to a turtle-like crawl with the end of the Apollo missions in 1972. Like the picture of our big blue marble from space seemed to tell us, we, serious science-fiction writers included, were going to have to concentrate on the earth and ourselves for a while, and no question here was as important perhaps than that implied by Dick of what exactly was our relationship with the technological world we had built and how to react in light of this world changing into something new with both promise and danger?

Even if the 70s and 80s were a period of retreat from the actual human settlement and exploration of space they were a heyday of dreaming about it. I was a kid then, and I loved it! There was Star Wars and Star Trek, Battlestar Galactica and a new Buck Rogers. Special effects, even if they seem primitive by today’s standards had gotten so good that one felt, at least if you were 10, like you were really there. And yet, we were nowhere near the things that could be dreamed stuck instead in low-earth orbit like David Bowie’s Major Tom.

This very ability to produce such vivid dreams of what could be was itself driven by technological changes that actually were happening a fact that became even more the case with the development of computers that were fast enough and cheap enough to make realistic computer animation possible- CGI- possible. Our waking dreams will become even more lifelike given the resurrection and inevitable improvement of 3D.

This new gap between our dreams and reality has resulted in a weird sort of anxiety in the generation, and no doubt mostly men of that generation, who grew up with the idea “the year 2000” would be some magical technological era of cites in space and the next stage of our interstellar adventure. No one, perhaps, has been more vocal in expressing this mindset than the technologists and billionaire, Peter Thiel who in a 2011 interview in the New Yorker stated the case this way:

One way you can describe the collapse of the idea of the future is the collapse of science fiction,” Thiel said. “Now it’s either about technology that doesn’t work or about technology that’s used in bad ways. The anthology of the top twenty-five sci-fi stories in 1970 was, like, ‘Me and my friend the robot went for a walk on the moon,’ and in 2008 it was, like, ‘The galaxy is run by a fundamentalist Islamic confederacy, and there are people who are hunting planets and killing them for fun.’

Doubtless, Theil downplays the importance of the revolution in computers and telecommunications that occurred in this period- a revolution he himself helped push forward. While states provide incapable or unwilling or both of pursuing Arthur C. Clarke’s vision of our future in space, a generation of bohemians and tech geeks succeeded in making his dreams about personal computers and a global communications network which had rendered location irrelevant come true. Here is Bill Gates in his Spock- like hyper-rational yet refreshingly commonsensical way on Peter Thiel’s slogan for technological pessimism:

We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.

I feel sorry for Peter Thiel. Did he really want flying cars? Flying cars are not a very efficient way to move things from one point to another. On the other hand, 20 years ago we had the idea that information could become available at your fingertips. We got that done. Now everyone takes it for granted that you can look up movie reviews, track locations, and order stuff online. I wish there was a way we could take it away from people for a day so they could remember what it was like without it.

Yet, Thiel and the cohort around him are not ones for technological resignation or perhaps even realism. Instead, they are out to make something like the sci-fi space fantasies they were raised on as kids in the 70s and 80s come true. Such is the logic behind what, so far at least, has been the first successful foray of a private company into space exploration- Elon Musk’s Space X. Believe it or not, two companies plan to send missions to Mars in the very near future: Inspiration Mars which hopes to launch a manned orbital probe and the even more ambitious Mars One which hopes to send a human crew to Mars that will not return- permanent settlers- in 2023 with an unmanned mission sending supplies to be sent only three years from now.

In a twist that I am not sure is a dystopian space version of The Truman Show or a real world version of Kim Stanley Robinson’s thought provoking Mars Trilogy the whole experience of the deliberately marooned Mars colonists of Mars One is to be broadcast to us earthlings safe on our couches. If this ends up like the Truman Show what we’ll have is the reduction of Stapledon’s or Clarke’s vision of space as a canvas upon which human destiny is to be written to a banal and way too expensive version of interstellar product placement that would be farcical if it wasn’t ultimately also a suicide mission. Though, instead of virgins in heaven the Martian marooned will see their families made rich by advertising royalties with the only price that they will never see them in person and given the distance will never be able to speak with them in real time again. Yet there are reasons to be optimistic as well.

Perhaps the Mars One mission, if it is successful, will result in something Robinson’s Mars Trilogy as described in Archeologies of the Future. According to Jameson, Robinson has provided us with a tableau in the form of human colonies on Mars upon which different definitions of what it means to be human and what the ideal society and what we should most value are played off against one another in a way that can never be finally and satisfactorily resolved. Mars One and missions of its type might give us a version of real-world science-fiction, where, as Philip K. Dick suggested it should be, the question is not where we are and what we can do but what we should be? Such adventures might help restore the canvass of the future, both by luring us away from our enticing versions of it which are too far from our grasp, and by allowing us to find some fate other than falling into the black pit of Vinge’s Singularity where our own still human future has been rendered irrelevant.

Then there is the future of science-fiction itself. As David Brin recently pointed out, his fellow science-fiction writer, Neal Stephenson, has launched a fascinating endeavor, Project Hieroglyph that encourages collaboration between science-fiction authors, artists and engineers in creating positive visions of the near human future.

Yet, there is another, even more important role I believe science-fiction can play.

Part of the reality of science and technology today is that it can be used to build radically different forms of society. As Douglas Rushkoff pointed out in this brilliant impromptu speech many of us thought the spread of the Internet was going to rise to one form of society- a society of free time and digital democracy, but instead the Internet has been used as a tool for the disappearance of the distinction between life and work, the application of ubiquitous surveillance by corporations and the government. In a time such as ours when the same technology can be used to pursue very different ends and used to support very different sorts of societies perhaps the primary role of science-fiction is to give us the intellectual and emotional skills necessary to negotiate our technological world- both as individuals and as a society. In this sense science-fiction, which seems to many just “kids’ stuff” is the most serious form of fiction we have, a tried and true road to the future.