When I was a kid there was a series on Nostradamus narrated by an Orson Welles surrounded in cigar smoke and false gravitas. I had not seen The Man Who Saw Tomorrow for over 30 years, though thanks to the miracle of Youtube I was able to find it here. Amazingly enough, I still remember Part 9 of the series in which the blue- turbaned, Islamic, 3rd antichrist allied with the Soviet Union plunges the world into thermonuclear war. I also remember the ending- scenes of budding flowers and sunshine signaling the rebirth of nature and humanity, a period of peace and prosperity to last 1,000 years. I think what must have made an impression on my young mind was the time frame of Nostradamus’ supposed predictions- with the Third World War to start sometime between the years 1994-1999, a time frame that was just close enough to scare the bejesus out of an already anxiety prone 9 year old. Thankfully, I was able to escape the latent fear induced by this not so well produced premonition when the USSR went belly up in 1991. Predicting the future is a tough job.

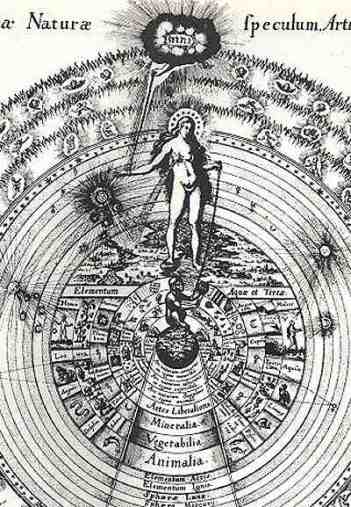

And what does it mean to predict the future anyway? Any idea that the future is somehow foreseeable seems to rely on some concept of determinism, but it’s not quite clear that all aspects of existence experienced by human beings are equally deterministic. Astrology seems to be a good example of how this works. Some of the things we experience do indeed seem to be determined, or better, their course stays essentially the same over vast stretches of time. It makes sense, even though it doesn’t work, to repackage and apply this determinism at the human level giving us a false but confidence building sense of control. The crazy thing, at least in terms of the future of society as opposed to the future of individuals, is that human beings seem prone to making predictions with bad outcomes, just consult the prophet of your choice. So, one wonders why something that is supposed to relieve anxiety- knowing what will happen- ends up doing the exact opposite and instead fills us with nostrodemian dred?

Maybe its all about the scale of the market. Palm readers who inform too many of their customers that their lives are about to go into the toilet probably go out of business pretty fast. When you’re dealing with mass markets though- fear sells. Better to write a book on the looming terrorist threat than one on just how peaceful modern societies are. You get more eyeballs when your piece has the word armageddon in the title than if it contains the word utopia.

Then there is the question of time horizon. As Stewart Brand suggested to the religious scholar Elaine Pagels the attraction of the ambiguity of a “prophetic” text like the Book of Revelation is that one can insert one’s own mortal timeline into it. Ray Kurzweil isn’t the first to predict the end of normal human affairs perilously close to the limit of his own likely lifespan.

Perhaps almost all predictions regarding the future are merely reflections of our own current anxieties, but this is not to say that our relationship to the future is merely all in our heads. Human beings and our societies exist along a continuum of time and this not only ties us to the what-is-not of the past but the what-is-not of the future as well. What we do today, if it proves relevant, will shape the future as much as the decisions made by those who preceded us shapes us today. To deny this is to deny something as real as the very present in front of us.

Yet, this future horizon is not merely something that applies to human civilization but to the earth and universe as a whole. Unless there is some cosmic mystery currently hidden from us, the earth will exists for something approaching 5 billion years before being consumed by the sun, and our universe, however dispersed because of expansion, will continue to have organized structures such as stars and galaxies- likely prerequisites for life- for far far longer than it has been in existence (13.5 billion years) into the realm of the unimaginable range of 100 trillion years.

There exists, then, a very likely future if not for our mortal selves or even humanity, for the cosmos and most likely life and intelligent life. We have something to predict about however silly such predictions will appear in retrospect. This gives us, I think, a great opportunity for a sort of “game”, an attempt to stretch our imaginations outward not so much in the hope that we can see like Welles’ Nostradamus the future that lies before for us so much as to see how broadly we can paint the canvas of what- might- be.

In this spirit, I invite you to participate in what I am calling The Far Futures Project.Those who wish can come up with their own predictions for the near and far future. Send them to farfuturesproject@gmail.com and I will post them on my blog Utopia or Dystopia. My only requirements are that you follow the template in terms of years found in my predictions below: 500, 10,000, 1 million, 1 billion, though I understand they will appear arbitrary to many. My second requirement is that you follow normal editorial standards with the awareness that these posts are geared towards general audience. Also, please provide some identifying information that will allow readers to connect with your ideas- especially links to your own work. My hope is to run the project for about a month, so here’s your chance.

You can see the first response to the call of the project in this entry by my friend and fellow blogger James Cross here.

As for me, here I go…

Rick Searle’s Far Future

500 years

The often painful transition that can be traced to changes in human society initiated by the industrial revolution in the 1800s has finally begun to reach equilibrium. Historians in the 2500s tend to see developments since the start of the industrial revolution as a set piece where humanity had to adjust itself to a new technological order, a new relationship with nature, new forms of inter-relations between and among peoples, and above all a need for humanity to decide both what it was and what it should be.

The technological question that the industrial revolution posed which took nearly 7 centuries to resolve was what would be the relationship between human beings and the rapidly evolving kingdom of machines?

Well before the 26th century there emerged a kind of modus-vivendi between human beings and machines, especially machines of the intelligent type. The employment crisis of the early to mid-21st century revolved around the widespread application of machine intelligence to all fields of economic, cultural, and political life, although no one yet could claim such machines possessed features of human intelligence such as consciousness. True Artificial General Intelligence or AGI remained a ways off, and never really replicated human intelligence, but would prove to be something quite different.

The consequence of the exponentially increasing processing power of computers was the ability to automate almost any formerly human process from the most intellectually challenging – classical composition or scientific discovery to the most simple production procedure. The capacity of machines to do almost any conceivable type of work road atop the ability to tap into human networks and feedback systems resulting in a kind of symbiosis between human intelligence and machines that whatever its human component left far too many people without gainful employment and would prove unsustainable not only economically but emotionally.

Numerous solutions to this dilemma were tried until a genuine modus vivendi was achieved. One attempted solution was to hive off human life from machines by providing people with a guaranteed income and allowing them to opt out of economic, intellectual and cultural pursuits- a solution that at the end of the day proved unsatisfying for far too many to be sustainable.

Another attempted solution was to tie human intelligence even closer to the new forms of machine intelligence by fusing the human mind with that of machines. This solution proved not so much unsustainable as unreachable in the form it had been articulated. Part of the problem stemmed from the fact that those parts of the human brain that were responsible for emotions, which human beings shared with other mammals, moved at such a glacial pace that they proved incompatible with the lightening fast cognition of machines. To propel emotional cognition faster seemed to inevitably result in various unwanted conditions from emotional deadening, to hyper-anxiety, to an accelerated sense of subjective time that canceled out the very longevity human beings had succeeded in creating.

The long lived humans of the 22th century embraced a slower and more reflective notion of time than their 21st century forebears and sought to limit machine intelligence from impinging on activities which embedded human life across the arch of time from the creation of art to the raising of children, the latter which came back into vogue after the prolonged “baby bust”.

Under what became the new post-capitalist order that took hold almost everywhere humans and machines were each given their unique domains based upon the question of scale and speed. Intelligent machines were extremely effective at running large scale entities- cities, armies, markets, coordinating reactions to pandemics and disasters for which the human mind was ill designed. There were also areas where the wetware of the brain proved far too slow- including moving human beings across space in the various incarnations of the 20th century automobile and airplane, fighting under conditions of modern, war or performing emergency surgery.

Machines were also able to fill dangerous (and degrading) economic niches human beings were ill suited to perform. This issue of scale and niche would prove the key to the future evolution of machines, an embedded tendency that someone in the far future when machines became the dominant “lifeform” in the universe would likely be unable to trace to its mundane economic and psychological origins.

A second question that had been raised by the industrial revolution was what the relationship between the natural world and humanity should be, a question that was intimately related to the issue of human population? Since the industrial revolution various societies had gone through a series of stages in terms of their relationship to the natural world a period of brute force rapaciousness unconcerned with environmental impacts followed by growing awareness and idealization of the natural world followed in the end by an increase in biological knowledge that allowed human beings to reverse, minimize, and isolate their impact on the biosphere.

Especially starting in the 22nd century, vast projects were launched that aimed to restore the natural world not merely to its conditions before the industrial revolution, but to those before human beings emerged from Africa over 10,000 years before. The rain forests of the world were restored. The auroch was genetically recreated and re-established in much of Eurasia along with more common species such as wolves and boar. The ancient chestnut forests and species that relied on them such as the passenger pigeon have been restored in North America, and the estuaries are alive with fish in a way they have not been since at least the 19th century. All the major African species, especially the great apes, have been restored to pre-modern numbers and prehistoric hominids resurrected and established in their ancient homeland of the African savannah. Long extinct species likely killed off by the hunting prowess of early humans- the Woolly Mammoth, Saber Tooth Tiger, Ground Sloth, and Giant Beaver brought back into existence and reestablished in the tundra of Siberia, Canada, and an iceless Greenland.

A solid majority of human beings- nearly 70%- now live in high density cities a move that has not merely aided in decreasing human population because of city-dweller’s smaller family sizes, but shifted the human impact on the environment from diffuse to compact allowing nature to reclaim enormous tracts of non-urbanized space. Especially important in this decreased spatial impact is the movement of farming into the cities. Vast aeroponic vertical farms in urban centers now produce the majority of the world’s food. Much of the Great Plains in North America has reverted to grassland and wildflowers. The return of the Buffalo has even resulted in a small number of Native American Blackfoot to return to their long lost traditional lifestyle- though they have kept the post-columbus horse.

For the first time in history there is effective global management of the earth’s biosphere. The global environment is constantly monitored not only from satellites but from a whole host of animal embedded sensors and cameras that provide real-time 24/7 monitoring of the earth’s environment. Invasive species and destructive diseases are caught, isolated and removed at lightening fast speeds.

Sophisticated AI directed modeling allows for extremely detailed predictions as to environmental impact permitting the tailoring of industrial and agricultural projects to promote healthy ecosystems, and directs the movement and actions within the human geography to best meet the needs of wildlife and the larger ecosystem.

This earth-scale environmental management is just one sign of the vastly increased capacity for global governance that was developed from the late 21st century forward. It origins lie in crises of both an environmental and geopolitical nature which that century was thankfully able to overcome.

Various times from the 19th through the 21st century the world was torn between different imperial orders. The 19th century imperial order of the Europeans was replaced by the 20-21st century American (and for a shorter spell, Soviet) imperial regime. From the early 21st century not just East Asia but the world had to adjust to the appearance of China in the global arena.

The world was on the verge of thermonuclear war not one but 3 times: The Cuban Missile Crisis (1963) the Russo-Japanese-Sino War fought over Chinese incursions into booming Siberia and the northern Pacific (2054) the Sino–Indian War, between China and India over China’s attempt to divert water from the Himalayas (2085). There was also a deep conflict between an alliance of “hot” countries and “cold” countries, that is between countries where the effects of climate change were sharp and devastating and those that had largely benefited from the change.

The Russo-Sino-Japanese war and the Sino-Indian war were both products not merely of the international order adjusting to the power of China but were responses to the reality of climate change. This eventually led to an alliance between China and many of the other hot countries that launched a policy to geo-engineer the world’s climate starting in 2095. In spite of worldwide protests and threats of war by the US and Russia, the hot countries began spewing tons of sunlight blocking sulfates into the atmosphere for a time turning the sky of the earth a gaudy orange. This did however have the intended effect, cooling the earth by almost 2 degrees and bringing rain and temperature distributions back to early 21st century norms. Disaster was averted but only at an incredible costs to humanity’s sense of itself and its relationship to the earth. The act did, however, start humanity on the right course.

Not even the massive migration flows of refugees fleeing from climate change got the world attention as much as the earth’s blue skies turning orange. The world came perilously close to war when an alliance of arctic countries- Russia, the US and Canada began shooting the tethered sulphur spewing Verne like Chinese dirigibles out of the sky. The Reykjavik Treaty which ended this conflict sparked a new era not only in the way human beings related to the earth’s environment but in the international relations between states. This new era of international cooperation was supported by a convergence in the systems of government found in most of the world’s countries and all of its major powers. The old argument between democracy and autocracy was no more.

Since the American (1776) and French (1789) revolutions people had been arguing over whether democracy was the best form of government. What occurred by the late 21st century was a convergence in both democratic and authoritarian regimes towards a form of government sometimes called responsive democracy that was neither representative nor direct but continuously scanned the public for feedback and direction as to government policy in the same way companies used social media to establish consumer preferences. Critics of responsive democracy claimed that it was easily manipulated by vested interests who were able shape citizen preferences, and that it robbed the public of its democratic responsibility to deliberate and decide. Yet, the model seemed unstoppable and by giving people a real voice in the face of the dominant oligarchies did seem to quell social pressures in countries as vastly different as the US and China.

In the centuries between 1800 – 2500 the major religious, philosophical, and cultural disputes would center around the question of what humanity was and what it should become. The dispute could be traced to Charles Darwin’s publication of The Origins of Species in 1857. What did it mean for the present and future of humanity to say that it had evolved from “lesser” species?

The 19th and early 20th centuries had seen the application of the darker aspects of the idea of human evolution with both racially justified imperialism and the Nazis. From the 21st through the 23rd century conflicts raged between the traditionally religious, environmentalists, and various shades of transhumanism, disputes that included not merely ideological struggles but inquisitions on all sides. Eventually, however, a widespread consensus began to take hold, a set of philosophical assumptions that lie underneath post-21st century understandings of the relationship between human beings and machines, the environment, and both domestic and international politics.

Humanity in a general sense was to be preserved on earth. Whatever their profound changes in health and longevity human beings in this era were essentially the same as human beings 10,000 years before. Earthbound machines were preserved as servants, while those of above human intelligence sequestered in a slim number of domains. Genetic transformation of human beings outside the realm of increasing health, strength, longevity or biological intelligence was discouraged, and biological cures promoted over bio-mechanical ones.

Those who wanted bold experiments such as creating a race of chimeras with mixed human and mechanical features, to merging into collective intelligences, could still have them, they just had to be pursued, given their perceived dangers to the survival of humanity, outside of the earth. Mars became the key destination in this regard, a kind of laboratory for all things post-human, but there would also be great floating cities in the solar system and even the first colonies sent out to closest living planets beyond the solar system…

10,000 years

Human civilization has reached the 10% milestone. 20,000 years living settled life in cities. During this period human beings have been the dominant form of intelligence and, on earth at least, have succeeded in suppressing the new evolutionary kingdom of the machines. This age is now coming to a close and traditional humans, still safe and thriving largely on earth, have receded far into the background of the evolutionary story now playing out in the Milky Way.

Despite their diminished status in the grand scheme of things, life for earthbound human beings has never been better. The average human being can be expected to live over 1,000 years. With so much investment in what in formerly human terms was the long term prosperity of society human beings have never been so inclined not to wage war against one another or let their society go to rot. The commitments of individuals to society, to an art, to persons, are long indeed, although few human relationships can be sustained over such time periods and as a consequence there are well developed rituals for “letting go” of marriage partners of friends and for a surprisingly large number even life itself. By far the greatest human works of art are created in this period as are the deepest works of philosophy. This is the true age of the “long form” single songs that run for months, novels comprised of hundreds of individual books, memoirs of love and loss felt over centuries.

Outside of the earth, humans and many more post-humans have terra-formed Mars and perhaps a billion now call that planet home. Over the millennia an innumerable number of sister earths have been discovered within a thousand light years of the solar system, though no other technological civilization has been discovered so far. Post-humans settlers have long reached the nearest living planets.

The descendants and creations of humanity that have continued to evolve and differentiate into a bewildering variety of forms across the width of a 5,000 light year span surrounding the earth. A large number of these creatures are the descendants of the silicon based forms humanity had invented far back in the 20th century- although silicon is no longer the dominant substrate and instead can be found a huge multiplicity of underlying elements.

1 million years

Humanity is now nearing the 2 million year mark, the average lifespan for a species.It has long since retired from the heart of things and watches with a mixture of awe and fear the goings on of the “gods” in the heavens.

Machines in space have begun an enormous surge of evolution akin to the Cambrian Explosion in the earth’s ancient history. From the big-picture view it can be seen that the kingdom of machines has been a way for life to overcome its limitations and expand into a much greater range of cosmic real estate. Carbon based life had evolved and could only thrive in a very narrow niche of the universe- stellar bodies that were not so large that the effects of gravity overwhelmed those of chemical reactions and not so small where the chemical reactions on which life was built did not occur with regularity.

Anywhere there is usable energy machines can be found, and in a diversity that matches that found in carbon based life- from the geothermal vents of a body like IO, where organisms are metallic-slugs able to withstand intense heat and pressure to the clouds of the gaseous giants where colonies of microscopic smart dust live off the planetary winds.

To study these forms in 21st century terms would require someone who combined the skills of an archaeologist an engineer and a biologist. Each machine form having a genealogy that tied it to some idiosyncrasy of human need and design in the distant past as well as evolving to meet the specific requirements of its own unique environment. Inside some of these machines can also be found still living biological cores- the machine itself being merely a means of survival and replication. One can only speculate as to the internal life of such beings whether the environment in which they currently live is the fabric of their consciousness or whether they live in a dream world of their past animal existence unaware as to their own current strangely transformed state.

If machine evolution allowed life to expand into vastness of space where gravitational dominance and chemical equilibrium formerly prevented it from taking root, there was also an expansion of life into brand new scales. The largest living organism ever found on earth, The Great Coral Reef, was a little over 1,200 miles (2000 km). In terms of social animals a Roman Empire like ant colony grew to be nearly 4,000 (6000 km) on the European Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts. Human civilization grew from the African Savannah to the earth, to the solar system, and near galactic living planets. Still nothing would match the superorganisms that would emerge from machines which would eventually grow to reach not merely a planetary, stellar, or solar system, but galactic and multi-galactic scales.

There were also scales below that of molecular that life, especially complex life, was unable to tap. Only the simplest of living organisms could exist on such small scales. Machine life, however, was able to move a million scales down to the range of atoms themselves becoming not merely the “living atomic scale matter” of some larger forms which thus even more strongly resembled organic life, but became a whole habitable zone unto itself, the home of the mechanical versions of bacteria the truly dominant form of both the organic and the mechanical world.

All this is very dangerous for organic life ,which not only continues to exist but thrives in the “cracks”- areas that are free from the terrestrially unbound silicon descendants. An enormous explosion of life, including intelligent life, is taking root in these cracks. Some of these are descendants of earth based life, but most have arisen completely independently. Whole civilizations rise and fall unaware of the story that plays out above them in the realm of the stars. And still, this remains merely the beginning of the beginning…

1 billion years

Humanity has long ceased to exist though the ultimate cause of their demise is unknown. The most likely scenario being that its defenses were worn down by the forays of some superorganism though there are rumors that the machine defenses humanity had built were themselves the culprit. Life, in one form or another, however, continues to move on. In fact, we have entered the golden age of life in both carbon based and silicon forms. The increasing amount of complex elements, especially of carbon from stars means that life is taking root on more and more planets, the story of evolution playing out across a diverse landscape of enormous scope. In this “lower world”, the world under the stars, stems a vast cacophony of forms- the splendor of life filling all the spaces of its possibility. Among these are a plethora of intelligent species and civilizations a great number which live out histories of creation and destruction with far too many destroying themselves upon reaching nuclear maturity.

Still, a good number, perhaps a slim majority, survive. From these civilizations come not merely art, music, stories, ideas, but also biographies- beings who have not merely lived but represent as it were a path of life, a story, embedded in the very fabric of reality. Silicon descendants, not just from the earth, but many places besides are likewise entering a new and golden phase.

Organic life is somewhat protected from the intrusions, exploitation or destruction at the hands of silicon based forms by the vastness of space and from the sheer diversity of environments where silicon forms are able to find usable energy. There is also, however, a new tendency for silicon protect the carbon based life from which it ultimately emerged.

It is unknown how this happened but it is thought that some especially prudent civilization programmed its machines with the purpose of protecting its organic progenitor. Somehow this purposing went rogue and there are quite a number of silicon forms that offer spheres of protection to not just the organic life forms from which they emerged but for all organic life they come across.

There appears to have been an unforeseen evolutionary advantage to this strategy. With the evolutionary experiments that emerges out of carbon based life being seen like the ancient invention of sex- a way to gain new “genes” and through diversity increase resilience. Some very patient and hands- off silicon based forms use carbon-based worlds as running simulations from which they can glean ways to increase their own internal complexity. Though, a good number have taken to actually “cultivating” intelligence on worlds- driving evolution in the direction of creating an intelligent species with technological potential from which they can glean even more diversity.

For those still living on planets the night sky has become even more brilliant than in the age of lifeless stars. A show of lights in unspeakably brilliant patterns the glow of enormous silicon descendants “talking” to one another across the vast stretches of space. Now is the age in which the “music of the spheres” has become real for not only is there light the cities in the skies sing to one another as well in music we can not even dream.