What often strikes me when I put the claims of some traditionally religious people regarding “eternal life” and the stated goals of the much more recent, I suppose you could label it with the oxymoronic phrase “materialist spirituality”, next to one another is just how much of the language and fundamental assumptions regarding human immortality these very different philosophies share.

Both the traditionally religious, especially those who fall under the somewhat simplistic label of “fundamentalist” and followers of materialist spirituality, whose worldview supposedly emerges out of science, share the essential goal of the survival of the individual. The ultimate objective for, say, a Bible thumping preacher from Tennessee and a technology ensconced singularitarian from San-Francisco are the same- the escape from the seeming inevitability of death and the survival of themselves into boundless eternity. Where they differ is on how to get there.

Just like Christianity or any other religion has its sects, those who embrace the goal of individual immortality under the umbrella of materialist spirituality have their sects as well. There are “mind-uploaders” who hope to transform themselves into eternal software, and some transhumanists who wish to so revolutionize human biology, perhaps with the addition of characteristics of advanced machines, so that death itself can be put off indefinitely. There are biologically centered immortalist- such as Aubrey de Gray, who hope to find the biological triggers that result in death and permanently turn them off, and others.

The reason both some (but by no means all) traditional religions and materialist spirituality share these almost identical goals stems, I think, from the fact that they come at the world from exactly the same frame of reference- that of the individual. But one might wonder what conclusions we would draw about the meaning and fate of life and sentience in the universe were we to adopt a different frame in which our own interests were not so clearly front and center. Is there a way to look at the relationship between life, especially sentient life, and time that makes the Universe seem meaningful even in light of our own personal death, or are those of us who trust the truth of science and are at the same time skeptical of materialist spirituality condemned to the conclusion drawn by the physicist Steven Weinberg that “The More the universe seems comprehensible, the more it seems pointless” ?

These questions were hitting me when I came across a book that had absolutely nothing to do with the subject of immortality: Dimitar Sasselov’s The Life of Super-Earths: How the Hunt for Alien Worlds and Artificial Cells Will Revolutionize Life on Our Planet. I will get into the nitty gritty of the book elsewhere, but here for me was the overall point of the work, for me a very optimistic point indeed- that the Universe is very young, and life itself only a little bit younger, and that life has a very, very long time before senescence in front of it.

We tend, I think, to be overwhelmed by the shortness of our individual lives when put in the context of the deep time scales science has revealed to us. And what is my life here, indeed, but a flicker in the context of billions of years? But if we step back from our personal lives for a moment and grasp the chain of living things upon which our being here has entailed at least some of this vertigo of time can perhaps be avoided.

I myself, and you, are here as the result of a chain of life that stretches backwards almost to the very beginning of the Universe. The same root found in the beginning of life on earth 4 billion years ago can be found in our DNA today. We are the bearers of a cosmically ancient inheritance that is comparable to the age of the Universe itself. Sasselov states it in the very plain language that: “ if the Universe were a 55 year old, Life would be a 16 year old” (p. 138)

If our roots stretching back into the beginning of time is important, for me the most optimistic message of Sasselov’s book is that the future of life, and not just life that originated on earth, stretches out even farther. Sasselov comes up with a good possible answer to Fermi’s Paradox- the fact that in conditions seemingly so ripe for life to have emerged the Universe is so damned silent. Sasselov’s theory is that the emergence of life is tied to the evolution of stars. The early Universe lacked the heavy elements that seem necessary for life, which need to be produced by long lived stars, so overtime these elements become more numerous and the types of stars that come to predominate are ones that, unlike earlier stars, readily produce a rich sea of these elements. The Universe is silent because we are likely to have been one of the very first intelligent civilizations to emerge at the beginning of this move towards the production of heavy elements- a just dawning golden age for life in the cosmos that will last at least 100 billion years into the future.

Moving away from Sasselov, the physicist, and very public atheist, Lawrence Krauss, in a friendly debate with fellow physicist Freeman Dyson seems to suggest that no complex, conscious entity in an expanding universe can be immortal given the current laws of physics. The physics are quite gnarly, but the in essence Krauss’ argument boils down to the fact that having an infinite number of “thoughts” is impossible in a Universe such as our own where the amount of energy is finite.

As is Krauss’ style, he tends to see the prospects of the impossibility for obtaining eternity, and the ultimate destiny of the Universe in a structureless heat-death in a spirit of humor charged doom. I do not, however, find this a reason to fret even jokingly, for think of the richness of lives- the number of sentient creatures, civilizations, worlds that according to Sasselov likely lie in front of us- the unfathomable depth of all that experience! There is a lot of living left to do, but this living it isn’t just in the future for there is a depth of lived time in the present to which most of us are probably unaware. Let me explain.

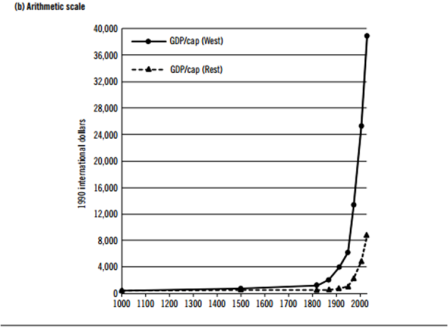

Around the same time I was reading The Life of Super-Earths I came across this wonderful graph from, of all places, The Economist.

The blurb in which this graph was embedded brought attention to the potential years of wisdom available to human beings on account of both the extension of the human lifespan and the rise in population and called on us to make use of it. It pointed out that with the milestone of 7 billion people in 2011 the aggregate age of everyone alive rose to 220 billion years. By the end of the 21st century:

The world’s population will have stabilized at just over 10 billion and those people will have accumulated 430 billion years of human experience between them.

The philosophical implications of this were not explored by the Economist, but think about it for a second. The number of subjective years lived today by the only fully sentient creature we know of- ourselves- is already more than ten times the chronological age of the physical universe! By the end of the century those subjective years will have grown to be around 30 times larger than the age of the Universe. In this sense life is not only older, but much older than the cosmos in which it swims and collectively might already be said to possess time on the scale of what any individual would consider eternity.

I think this reframing of the issue of eternity opens up deep questions that need to be addressed by those looking at immortality from a more individualistic bent. For example, perhaps the most outspoken proponent of “ending death” in a biological sense is Aubrey de Grey. In a talk at TEDMED de Grey admits the obvious- that extending the lifespan of those already alive in a world of finite resources would inevitably result in people having less children. Strangely, he seems to think that this indefinite lifespan is something we are morally obligated to make possible for the current generation and the one in the immediate future. His position seems to ignore the generations after whose potential lives might shrink to be near zero as people defray having children in order to live indefinitely. De Grey’s position seems to become even more suspect when we place it in the context of subjective time mentioned above.

Unless there is some flaw in my logic, it seems that in a Universe where life can not exist infinitely, which is what Krauss’ work shows, or in a world of finite resources if an individual (or a society) chooses to forgo having children in the name of indefinite lifespan for individuals the amount of subjective time available in the Universe as a consequence goes down. To use an extreme example: imagine a Universe with only one sentient being that lived for a very very long time- though not infinitely. Such a Universe would have experienced much less subjective experience than a large number of sentient beings that lived a briefer but rich amount of time where life as a whole lasted for an equal duration. The same would hold for a Universe in which one civilization monopolized sentience when contrasted with a Universe with a rich plurality of civilizations. Less diversity, less full existence.

This is not an argument for maximizing the number of children. For the decision to have a child represents a deeply personal choice and commitment and brings other moral factors into play not the least is the one of the quality of life for individuals and the impact of human lives on diversity elsewhere in the biosphere meaning the question of sustainability.

Yet, there would appear to be a threshold where increasing the lifespan of individuals at the cost of forgoing new lives is cosmically impoverishing. Thus, before the human immortality project can be embraced without deep moral reservations, some notion of how this project relates to the prospects for potential life in the future (extending even beyond humanity to its consequences for the life of the earth’s biosphere) need to be addressed. Collective “immortality” appears to have the moral high ground on types of immortality that are focused on individuals alone.

The stunning thing is that many of the world’s traditional religions already appear to have an intuitive sense of this collective immortality. The way to immortality for the ancient Greeks was fame in the service to one’s polis, for many of the other religions the path to immortality lies in the abandonment of the ego and the adoption of selflessness and service to others. Traditional humanists often thought of themselves as links in a great chain of poets, writers, musicians, philosophers or scientists.

For what it is worth, proponents of today’s materialist spirituality in their focus on the individual seem to have broken themselves off from this great chain of life and thought. The wonders of science may or may not someday bring us escape from individual death, but all we can reasonably do for now are things we have always done: raise our children, write a poem, discover a truth, compose a song, help a fellow human being, or preserve a political community or wilderness. In these ways we add the short time of our existence to a future of life that stretches out long in front of us in a Universe filled with a plethora of species and civilizations we can scant imagine. A world where, for all practical purposes, life and thought are indeed already, eternal.