There’s an element to the end of the Trump presidency that is more than vaguely reminiscent of waking up after a particularly bad college house party or a car crash. Upon scanning the damage and chaos there is a question that demands an honest and immediate answer- “What the hell happened?” Indeed, what the hell happened? It’s hard to remember, but I’ll try.

Back in 2016, the United States, on the basis of its democratically flawed electoral college system elected a completely unqualified reality TV star (who had become famous by pretending to be a successful businessman) to the most powerful political position in the world. Donald Trump was elected even after he had on multiple occasions openly denied adherence to long standing democratic norms. That he won that election was partly the consequence of the leadership of the Democratic party having crowned as its presidential candidate one of the most unpopular and partisan figures in American politics- Hillary Clinton. But above all his victory came after a series of devastating failures either caused, or never properly addressed, by political elites- the Iraq War, the Financial Crisis, and the Opioid Epidemic- to name just three. Blowing up the system was the national mood, and Donald J. Trump was dynamite.

The Trump years were every bit as whacked as the reality TV or New York tabloid scene that had made the man famous with one chaotic or disturbing incident replacing another in a never ending stream, so that yesterday’s outrage was always lost down the memory hole, shoved into oblivion by today’s. It was boom time for cable news, partisans, and sycophants meaning nothing much had changed at all except for the ratings.

Many of us knew this couldn’t end well even before we were confronted by the images of children in cages while the first lady mocked them with her jacket reading “I ReallyDon’t Care, Do you?” We knew Trump would likely kill a lot of people, we just figured it’d be the types of people US presidents usually killed- people “over there”- who don’t look like us. Instead, we got 500,000 dead Americans from a plague Trump thought it was a president’s job not to panic us about. Thinking we could replace functioning, if flawed, institutions with televisual fantasy proved to be a bad idea after all.

When as a result of his incompetence the American public decided it had had enough of Trump and voted him out of office he decided his show couldn’t actually be canceled. We then got to see a new side of Trump, and it was terrifying. What his loss in the election gave Trump, which he never possessed before, was a plot, a clear objective which he would pursue by utilizing characteristics that had always been apparent- his authoritarian and anti-constitutional impulses. But even then Trump found himself chasing after the subplot that was always his one and true love- the art of the grift.

Trump in many ways is the culmination of the long standing American desire to substitute make-believe for reality, and what he proved with his presidency is that even in the face of illusion induced catastrophe a large number of Americans are unwilling to give up their fantasies. Claire Malone put it very well:

“Up until the Trump era, partisans had made studious attempts to craft their arguments in at least a simulacrum of fact. Trump didn’t bother much with that, and it turned out, the vast majority of Republican voters didn’t mind.”

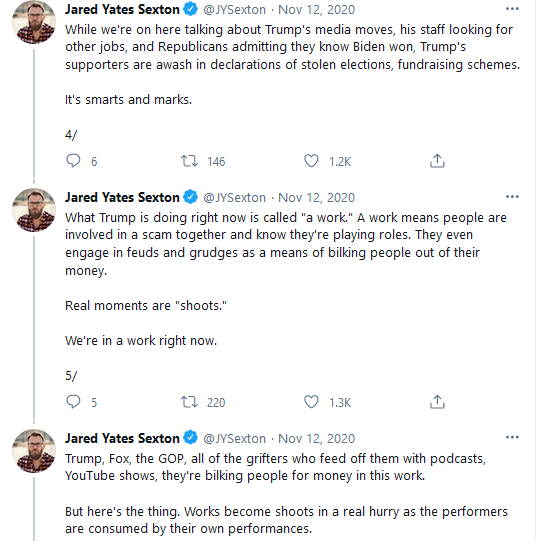

Indeed, perhaps the best way of understanding Trumpism as a political form isn’t through comparison with traditional political “isms” like fascism or populism but in light of a type of collective make-believe- professional wrestling- where Trump is very much at home. This was the view laid out by Jared Yates Sexton in a Twitter thread back in November of last year, months before we got Trump’s deadly putsch at the Capitol. It’s a perspective which accurately predicted almost all of what was to occur during the harrowing months that followed the 2020 election.

The grift of the stolen election was largely a work whose purpose was to fleece the marks, but over time it became a shoot and burst into reality as something real- but only in the minds of believers. Indeed, at one point the belief itself became its own justification, the election deemed illegitimate not because there was substantial proof of cheating, but because nearly one half of the country believed there had been.

What Trump himself believed is ultimately an unanswerable question. I’m not even sure the man has what would normally be called beliefs. He’s not so much Asimov’s “Mule” throwing a wrench into the predictions of psychohistory by manipulating the crowd with his mesmerizing powers, much less the converse of Hari Seldon able to leverage the fissures of society to bend history in his direction, than he is a Dorian Gray like mirror both enchanting and horrifying the masses with their own reflection. A man created by television whose fans treated an insurrection like a reality TV show where they played starring roles.

At least up until the day after the 2020 election when it was clear he had lost, the Trump show was always scripted in real time, written on the fly based on the reaction of its viewers on Twitter, and especially on shows like Fox and Friends and its related ilk. And as with many hit shows accelerating towards its end this one became more and more detached from reality and bizarre. Instead of having a coup led by a figure like Kenan Evren we get one whose insane plot was drawn up by the MyPillow guy. The most loyal of Trump fans, like with any fandom, lost sight of the plot and found themselves holed up in subcults on Reddit and Gab where reality goes to die.

Very little about Trumpism as a political phenomenon was actually innovative. It was just louder. The most groundbreaking aspect of the show, which had formerly confined itself to televised propaganda, stadium rallies, and way too many flags with a splash of updated direct marketing via FaceBook, wasn’t hit upon until the last few months of the Trump administration after the election had already been determined.

In his desperation Trump managed to turn a political conspiracy theory into a mass role playing game with feeder series on cable TV, and an online component where devoted viewers could document the “steal” and upload the “evidence” to YouTube- like some Bellingcat from hell. It was a show filled with cliffhangers that called for heroes who turned out to be villains in the form of the Supreme Court and Mike Pence, reaching its climax with a live steamed, mass participatory, new American Revolution at the Capitol.

If that sounds like a role playing game, or like it was unhinged, it’s because it was both. In large part this was a consequence of the Trump show in its final days having merged with the online Trump cult Qanon, itself a kind of demented RPG. Ross Douthat has probably explained it best:

“But he wanted more, he wanted a way to actually stay in office, and since no Republican with real power would actually do a coup for him, he turned fully to the fantasy world — which gladly supplied him with story lines, narratives, first the Kraken and then the fixation on Mike Pence as a deus ex machina.

And because Trump is, however incompetently, actually the president and not just a character in an online role-playing game, by turning to the dreamworld he made himself a conduit for the dream to enter into reality, making the dreamers believe in the plausibility of direct action, giving us the riot and its dead.”

There was something very Gunpowder Plot-ish about the whole thing- the attack on the seat of government, the QAnoners’ blood lust for decapitating the entire ruling class so the supposed righteous could assume the seat of power. It was nuts, but not just nuts in the obvious detached from reality way that’s the source of much of the mockery against the cult, but nuts in a deeper theoretical way.

The Qs are mistaken as to where they are in history and as a consequence have got their theory of revolution all wrong. You can’t overthrow a modern state by just cutting off a certain number of the elite’s heads. The state has long ceased to be an entity attached to the bodies of its rulers . Power no longer lies in persons but in systems, as some of them no doubt realized after they had been barred en mass from spreading their crazed conspiracies on social media.

Thankfully, Trump’s brand of demagoguery doesn’t deal well with systems. If one labeled it fascism it would have to be a very peculiar sort of stochastic fascism that makes use of all the standard fascist tropes to rile up the mob, but then lacks the discipline to actually do much of anything after its been crowd surfed into power.

For years now both the left and the right have terrified (and mobilized) themselves based on the twin boogiemen of the past century- fascism and communism- rising from the grave. The reason why such fear is largely misplaced is that the social conditions that gave rise to the totalitarian movements of the 20th century have largely disappeared in the 21st. The heart of fascism always lay in the millions of military veterans who had their souls deformed by the Great War and had been inculcated with a worship of action and obedience. The heart of socialism lay in an industrial proletariat who had been taught the dual lessons of mass organization and class war in the factories, while state communism only ever existed in societies that had been industrialized from the top down, their peasants forced into modernity at the barrel of a gun.

These are social conditions that are largely gone, especially in the US and Western Europe, where warfare is no longer a mass phenomenon because it has returned to being a profession, while decades of neoliberalism, globalization, and automation have reduced the industrial proletariat to little but a shadow of its former self. Trumpism did indeed have some affinity with classical fascism- sharing its ethno-nationalism, anti-intellectualism, and affection for conspiracy theories. And like fascism, Trumpism was also a movement widely supported by the petit-bourgeois who both in the 1930’s and today, found themselves crushed in a vice between capital and the poor. Nevertheless, Trumpism lacked the core commitment of fascism to the power and legitimacy of the state.

In only a very limited sense, we ran Sinclair Lewis’ experiment from his dystopian novel It Can’t Happen Here and proved his hypothesis wrong. The United States with its heterogeneity of cultures and divided power centers would not fall prey to an American fuhrer. But we shouldn’t congratulate ourselves too quickly. In the face of much less pressure, and with many more structural advantages, we proved ourselves just as ripe for a demagogue as any other people in history, and exactly the type of figure the country’s founders had designed our system of government to protect us from. Nor should we, even given all the historical differences between ours and the conditions that gave rise to the totalitarian movements, completely discount Sinclair’s warning.

It Can’t Happen Here concludes with a populist, racist president- Buzz Windrip- who had overthrown the American government being exiled to France and a military figure- General Haik- seizing control of the government. What the rise, containment and fall of Trump signal is that there is a disturbing likelihood that such a scenario lies in our future as well.

If one party continues to put fantasy-obsessed maniacs into office the attempts by the institutional forces of the state to contain them might become more and more strained and contorted. The problem, for those of us who see it as such, is not that Trump’s ties to Russia shouldn’t have been investigated, or his irresponsible impulses in foreign policy contained, or his desire to use the security forces of the state against his domestic political foes stymied, or his possession of the nuclear codes after an attempted coup by his own loyalists nullified, it’s that these moves by the institutions of the state are in tension with the idea that power in a democracy is the product of elections.

The fact that elections and the constitutional system itself appears to be no longer capable of empowering a responsible political class that polices its own members who are committed to that system beyond the horizons of their own personal power should terrify us. What is also deeply disturbing is how, at the same time, power has slipped from public entities who are subject to political sanction to private entities who suffer no such constraints. Public institutions, especially the parties, no longer act as a kind of bottleneck and lens through which the cacophonous voices and desires of the demos is filtered of noise and made coherent. The process of representation no longer works like it used to, indeed many have forgotten what representation, at least as conservatives have long defined it, actually means.

Instead what counts as political reality is decided by private corporations, such as Fox and Twitter, or becomes a matter of direct pressure by hyper-mobilized groups who take their anger and desires directly to those in power through threats or protests (sometimes armed). Rather than reform our political system, or transform it into something that better reflects contemporary conditions, we seem bound and determined to compound its flaws until our only choices left will be between the rule of capital or the chaos of the mob.

Even if the possibility for radical transformation is far-fetched in the US context, practical reforms are desperately needed. The flow of information between representatives and their constituents has become so distorted- through a gerrymandered electoral system, the influence of money, or by a primary and communications network that empowers only the most motivated and extreme voices- the pragmatic sanity of the supermajority is ignored. At the end of the day, Americans are a middle of the road people, attracted to common sense solutions to almost universally recognized problems. It’s a reality that doesn’t goose the ratings and that one wouldn’t guess existed by watching cable news.

For a day or so after the events of 1/6 I had the naïve hope that the shocking spectacle of it would snap our political class and the American public back to reality. The Potemkin Civil War, which had proven so lucrative for media and political parties on both the left and the right had for a moment broken into reality, but sadly, its image wasn’t frightening enough for those propelling the conflict to let go of the grift.

Trump’s acquittal by the Senate means the golden age of the grifter isn’t over quite yet, and may have even just begun. Whether that means Trump will go the dangerous route of claiming to be the president in exile like the popes of Avignon, is mortally wounded by lawsuits, or slowly disappears from public consciousness due to social media bans is anybody’s guess. At the very least I can stop worrying daily about what mischief he’s up to until 2024 even if I can’t say the same for the conditions that brought us Trump in the first place.