If someone on the street stopped and asked you what you thought was the meaning behind Oscar Wilde’s novel A Picture of Dorian Grey you’d probably blurt out ,like the rest of us, that it had something to do with a frightening portrait, the dangers of pursuing immortality, and, if one remembered vague details about Wilde’s life, you might bring up the fact that it must have gotten him into a lot of trouble on account of its homoeroticism.

This at least is what I thought before I sat down and actually read the novel. What I found there instead was a remarkable reflection on human consciousness all the more remarkable because in 1890 when the novel was published we really had no idea how the mind worked. Wilde would arrive at his viewpoint from introspection and observation alone. His reflections on thought and emotion are all the more important because many of the ways his protagonist becomes unhinged from the people around him, and thus cursed to a fateful demise, are a kind of amplified intimation of what social media is doing to us today. Let me explain.

The science writer and poet, Diane Ackerman in her book An Alchemy of the Mind list three ways evolution has “played tricks” on us: 1) We have brains that can imagine states of perfection they can’t achieve, 2) We have brains that compare our insides to other people’s outsides, 3) We have brains desperate to stay alive, yet we are finite beings that perish. (p. 6). Although the novel is not discussed by Ackerman, A Picture of Dorian Grey explores all three of these “tricks”, though the third one, which is perhaps often thought to be the main subject of the novel is in fact the least important one in terms of the story and its meaning.

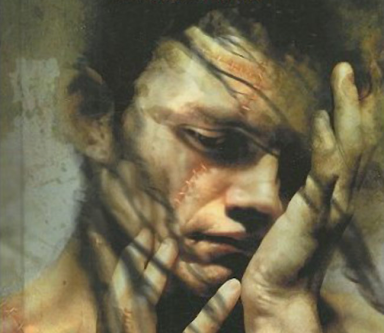

The whole tragedy of Dorian Grey begins, of course, when Dorian looking upon his portrait by Basil Hallward dreams he could exchange his own temporal youth for the youth frozen in time by the painter:

… if only it were the other way! If it were I who was to be always young, and the picture that was to grow old! For that-for that- I would give everything! Yes, there is nothing in the world I would not give! I would give my soul for that! (25-26)

What drives Dorian to make his “deal with the devil” is his ability to imagine something that cannot be- his own beauty frozen in time- like the dead portrait- while he himself remains living. Of course, the mark of maturity (or sanity) is being able to tell the difference between our dreams and reality and learn somehow to accept the gap. What this devil’s wager brings Dorian will be a failure to mature though this will not mean that he will not experience the other emotional manifestation of aging that emerges if one fails to grow with experience- that is degeneration and corruption.

If we do ever master the underlying mechanisms of aging, especially cognitive aging, this question of maturation and development seems sure to come up. We may all wish were as good looking as when we were 19 or as deft on the basketball court, but few of us would hope for the return of the emotional rollercoaster of adolescence or the lack of foresight we had as children. Many of these emotional changes from youth to middle age and older are based upon our accumulated experience, but they also follow what seems to be a natural maturing process in the brain. What we lose in reflex- time and rapid memory recall we more than makeup for in our ability to see the big picture and exercise emotional control. Aging in this sense, can indeed be said to be healthy.

These changes are certainly a factor when it comes to the relationship between aging and crime. Not only do the rates of crime track chronological age with the majority of crimes committed by young men in their late teens and early 2o’s, but rates of recidivism for those convicted and imprisoned plummets by more than half for those 59-69 years old versus 18- 24 year olds.

What does all of that have to do with Dorian Grey? More than you might think. In the novel it is not merely Dorian’s physical development that is arrested, but his emotional development as well. The eternal youth goes to parties, visits opium dens, visits brothels and does other things that remain unnamed. He does not work, does not marry, does not raise children. He has no real connection with other human beings besides perhaps Lord Henry Wotton who has introduced him to the philosophy of Hedonism, though even there the connection is tenuous. Dorian Grey gains knowledge but does not learn, neither from his own pain or the pain he inflicts on others. Had he been arrested he would make the perfect recidivist.

Yet, it is in Ackerman’s second trick she thinks evolution has played on us: “having a brain that compares our insides to others outsides” that the real depth of The Picture of Dorian Grey can be found, and its most important message in light of our own social media age. Indeed the whole novel might be thought of as a meditation on that simple, but universal, trap of our own nature. But first I must discuss the question of empathy.

Dorian manages to ruin almost every life he touches. His first romance with the poor actress Sibyl Vane ends in her suicide, his blackmail of Adrian Singleton leads to his suicide as well. He will murder Basil Hallward the person who perhaps loved him most in the world. There are countless other named and unnamed victims of Dorian’s influence.

What makes Dorian heartless is that everyone around him becomes a mere surface, a plaything of his own mind. It was his cruelty to Sibyl Vane that led to her suicide. Hallward who plays the Mephistopheles to Dorian’s Faust explains the actresses death to him this way:

No she will never come to life. She has played her final part. But you must think of that lonely death in the tawdry dressing- room simply as a strange fragment of some Jacobean tragedy, as a wonderful scene from Webster, or Ford or Cyril Tourneur. The girl never really lived so she never really died. To you at least she was always a dream a phantom… (103)

To which Dorian eventually responds regarding the girl’s death:

It has been a marvelous experience! That is all. I wonder if life has still in store for me anything as marvelous. (103)

We might reel in revulsion at Dorian’s response to the death of another human being, at his stone- heartedness in light of the pain the girl’s death has brought to her loved ones, a death he bears a great deal of responsibility for, but his lack of empathy holds up a mirror to ourselves and might be something we need to be more fully in tune with now that our digitally mediated lives allow us to so much more easily turn real people into the mere characters of our own life play.

There was the tragic case of Rebecca Sedwick a 12 year old girl who killed herself by jumping from an industrial platform after repeated bullying from her peers including multiple incitements by these young women for the girl to kill herself. The response of one of the bullies to the news of Rebecca Sedwick’s death was not horrified remorse, but this message which she posted on FaceBook:

Yes I know I bullied Rebecca and she killed herself, but I don’t give a f—k.

Two of the bullying girls had been arrested and charged with felony harassment, though the charges have now been dropped.

In addition to this kind of direct cruelty there is another form of digitally mediated cruelty where people are willing spectators and sometimes accomplices of heinous acts: snuff films, pornography with some participants unaware that they are being filmed, especially the epidemic of child pornography. Deliberate cruelty to animals is another form of a digitized house of horrors as well.

This cruel pixelization of human beings (and animals) can strike us in seemingly innocent forms as well, as the media critic Douglas Rushkoff wrote of our infatuation with reality TV in his Present Shock :

We readily accept the humiliation of a contestant at the American Idol audition- such as William Hung, a Chinese American boy who revived the song “She Bangs” – even when he doesn’t know we are laughing at him. The more of this media we enjoy the more spectacularly cruel it must be to excite our attention…. (pp. 36-37)

On top of this are all the kinds of daily cruelty we engage in with our simulations- violent video games, or hit shows like “The Walking Dead”.

Is all of this digital cruelty having an effect on our ability to feel empathy? It appears so. Researchers are starting to pick up on what they are calling the “empathy deficit” a decline in the level of self-reported empathetic concern over the last generation. As Keith O’Brien wrote in The Boston Globe:

Starting around a decade ago, scores in two key areas of empathy begin to tumble downward. According to the analysis, perspective-taking, often known as cognitive empathy — that is, the ability to think about how someone else might feel — is declining. But even more troubling, Konrath noted, is the drop-off the researchers have charted in empathic concern, often known as emotional empathy. This is the ability to exhibit an emotional response to someone’s else’s distress.”

Between 1979 and 2009, according to the new research, empathic concern dropped 48 percent.

The worst case scenario that I can think of is that we are witnessing an early stage of the shift away from the non-violent society, we, despite our wars, created over the 19th and 20th centuries. A decline that Steven Pinker so excellently laid out in his Better Angels of Our Nature.

Pinker traced our development of a society incredibly less violent and less accepting of violence than any of its predecessor. We appear to have a much more developed sense of empathy than any society in the human past. One of the major players in this transition from a society where cruelty was ubiquitous to one where it invokes feelings of revulsion and horror Pinker believes was the rise of reading, of universal literacy and especially the reading of novels.

Reading is a technology for perspective-taking. When someone else’s thoughts are in your head, you are observing the the world from that person’s vantage point. Not only are you taking in sights and sounds that you could not experience firsthand, but you have stepped inside that person’s mind and are temporarily sharing his attitudes and reactions.

Stepping into someone else’s vantage point reminds you that the other fellow has a first-person present-tense, ongoing stream of consciousness that is very much like your own but not the same as your own. It’s not a very big leap to suppose that the habit of reading other people’s words could put one in the habit of entering other people’s minds, including their pleasures and pains.

What visual/digital media fails to give us, what still allows even bad novels to give great films a run for their money, is any real grass of characters internal lives. The more cut off from other’s internal lives we become, the more they become mere surfaces with which we can play the “film” of our lives the only internal life we’ll ever know with certainty to be real.

This failure to recognize other’s internal lives is like the flip-side of “having brains that compare our insides to other people’s outsides” to which I will now after that long digression return. Perhaps all of the characters in The Picture of Dorian Grey mistake the surface for the truth of things. This is the philosophy of Lord Wotton, the origin of Dorian’s dark pact, and even infects the most emotionally attuned character in the novel, Basil.

In one scene, Basil comes to warn Dorian about his growing public infamy. It is a warning that will eventually lead to Bail’s murder at Dorian’s hands. The painter cannot believe the stories swirling around about the unaged man who once sat in his studio and was the muse of his art. Basil gives this explanation for his disbelief:

Mind you, I don’t believe these rumors at all. At least I can’t I can’t believe them when I see you. Sin is a thing that writes itself across a man’s face. It cannot be concealed. People talk sometimes about secret vices. There are no such things. If a wretched man has a vice, it shows itself in the lines of his mouth, the droop of his eyelids, the moulding of his hands even. (149-150)

Basil believes Dorian is good because his outside is beautiful, or he confuses his own virtue with Dorian’s appearance. This mistaking of outside with inside is the curse of the FaceBook generation. As Stephen Marche explained it in his article Is FaceBook Making Us Lonely? we have put ourselves in a situation where we are constantly confusing people’s lives with their social media profiles and updates where we often only see photos the beautiful kids making crafts- not the temper tantrums, the wonderful action packed vacation- not the three days in the bathroom with the runs, or the sexy new car or gorgeous home rather than the crippling car and home payments.

In other words, we assume people to be happy because their digital persona is happy, but we have no idea of the details. We should be able to guess that, just like us, the internal lives of everyone else are “messy”, but this takes the kinds of empathy we seem to be losing. We are stuck with a surface of a surface and are apt to confuse it with the real. To top it all off we have to then smooth out our own messiness for public consumption, or worse fall into a pit where we try to dig out of our own complexity, so we like the personas of others we mistake for real people can be “happy”.

Here’s Marche:

Not only must we contend with the social bounty of others; we must foster the appearance of our own social bounty. Being happy all the time, pretending to be happy, actually attempting to be happy—it’s exhausting. “

So what of the last of Ackerman’s tricks of evolution that “we have brains desperate to stay alive, yet we are finite beings that perish.” Although it might seem surprising, the exploration of this desire to be immortal is the element least explored in A Picture of Dorian Grey.

The reason for this is that Dorian is not so much interested in immortal life as he is in eternal youth, or better the eternal beauty that is natural for some in their youth. A deal with the devil to live forever, but be homely, is not one vain Dorian would have made.

Dorian is certainly afraid of dying, he is terrified and sickened by the fear that Sibyl’s brother will kill him. But in the short space between the appearance of this fear and Dorian’s actual death there is no room to explore Wilde’s thoughts regarding death.Dorian does not live forever, he dies a middle aged man.

A new radio series The Confessions of Dorian Grey does explore this theme barely developed by Wilde, imaging a Dorian Grey who lives rather than dies and takes his corruption through different times periods after the fin-de siecle. I look forward to seeing where the writers and producers take the theme.

___________________________________________________________________

In the back of my version of A Picture of Dorian Grey is a wonderful essay The ‘Conclusion’ to Pater’s Renaissance by Wilde that is really about what it means to be alive and to be conscious and the place of art in that. Wilde writes:

… the whole scope of observation is dwarfed to the narrow chamber of the individual mind. Experience already reduced to a swarm of impressions, is ringed round for each one of us by that thick wall of personality through which no real voice has ever pierced on its way to us, or from us to that which we can only conjecture to be without. Every one of those impressions is the impression of the individual in his isolation, each mind keeping as a solitary prisoner its own dream of a world. (226)

Wilde wanted to grab hold of the fleeting impressions of life for but a moment and locate the now. Art, and in that sense “art for art’s’” sake was his means of doing this a spiritual recognition of the beauty of the now.

What ruined Dorian Grey was not the or sentiment or truth of that, though Wilde was exploring the dangers implicit in such a view. The black box nature of our consciousness, the fact that we create our own very unique internal worlds, is among the truths of modern neuroscience. Rather, Dorian’s failure lie in his unwillingness to recognize the “dream of a world” of others was as real and precious as his own.