As readers may know, a little while back I wrote a piece on Steven Pinker’s Better Angels of Our Nature a book that tries to make the case that violence has been on a steady decline throughout the modern era. Regardless of tragedies such as the horrendous school shooting at Newtown, Pinker wants to us know that things are not as bad as they might seem, that in the aggregate we live in the least violent society to have ever existed in human history, and that we should be thankful for that.

Pinker’s book is copiously researched and argued, but it leaves one with a host of questions. It is not merely that tragic incidents of violence that we see all around us seem to fly in the face of his argument, it is that his viewpoint, at least for me, always seems to be missing something, to have skipped over some important element that would challenge its premise or undermine its argument, a criticism that Pinker has by some sleight of hand skillfully managed to keep hidden from us.

I think an example of this can be seen in Pinker’s treatment of the decline of torture and fall in the rates of violent crime. Both of these developments, at least in Western countries, are undeniable. The question is how are these declines to be explained. What puzzled me is that Pinker nowhere even mentions the work of the late philosopher, Michel Foucault, a man who whatever the flaws and oversimplifications of his arguments, thought long and hard about the questions of both torture and crime. In fact, Foucault is the scholar whose work is most associated with these questions. It is a very strange oversight, for Pinker does not bring up Foucault even briefly to dismiss his views.

It seems, I am not the only person who asked this question for on his website addressing frequently asked questions Pinker gives the following explanation for ignoring Foucault:

Questioner: You obviously must discuss Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, the book that explains the decline of judicial torture in Europe.

Pinker: Actually, I don’t. Despite being a guru in the modern humanities, Foucault is not the only scholar to have noticed that European states eliminated gruesome punishments, and his theory in particular strikes me as eccentric, tendentious, and poorly argued. See J. G. Merquior “Charting carceral society” in his book Foucault (UC Press, 1985), for a lucid deconstruction.

I wanted to see what this “lucid deconstruction” of Foucault by Merquior (Pinker is nothing if not clever- Foucault is a patron saint to literary deconstructionist), so I checked it out.

Here is how Merquior introduces Foucault’s Discipline and Punish:

Foucault once called it ‘my first book’ and not without reason: for it is a serious contender for first place among his books as far as language and structure, style of organization and ordering of parts go. It is not a bit less engrossing than Madness and Civilization, nor less original than the order of things. Once again Foucault unearths the most unexpected of primary sources; once again his reinterpretation of the historical record is as bold as it is thought provoking.” ( Foucault p. 86)

This is the guy Pinker asks us to turn to for a rebuttal of Foucault?

Merquior does have some very valid arguments to make against Foucault, more on that towards the end, but first the views that Pinker does not discuss- Foucault’s view of the rise of the prison.

The theory that Foucault lays out in his Discipline and Punish which provides a philosophical history of the modern prison is essentially this: The prison emerged in the late 18th and 19th centuries not as a humanitarian project of Enlightenment philosophes, but as a disciplinary apparatus of society in conjunction with other disciplinary institutions- the insane asylum, the workhouse, the factory, the reformatory, the school, and branches of knowledge- psychology, criminology, that had as their end what might be called the domestication of human beings. It might be hard for us to believe but the prison is a very modern institution- not much older than the 19th century. The idea that you should detain people convicted of a crime for long periods perhaps with the hope of “rehabilitating” them just hadn’t crossed anyone’s mind before then. Instead, punishment was almost immediate, whether execution, physical punishment or fines. With the birth of the prison, gone was the emotive wildness of the prior era- the criminal wracked by sin and tortured for his transgression against his divine creator and human sovereign. In its place rose up the patient, “humane” transformation of the “abnormal”, “deviant” individual into a law and norm abiding member of society.

For Foucault, the culmination of all this, in a philosophical sense, is the Panopticon prison designed by Jeremy Bentham (pictured above). It is a structure that would give prison officials a 24/7 omniscient gaze into the activities of the individual prisoner and at the same time leaves the prisoner completely isolated and atomized. In the panopticon Foucault sees the metaphor for our own homogenizing conformist and totalizing society.

What Foucault succeeded in doing in Discipline and Punish was putting the horrific judicial torture of the pre-Enlightenment era and post-Enlightenment policy of mass imprisonment side-by-side. In doing this he goads us to ask whether the system we have to today is indeed as humane, as enlightened, compared to what came before as we are prone to believe.

This is exactly what Pinker responding to a question on imprisonment does not allow us to do:

Questioner:What about the American imprisonment craze?

Pinker: As unjust as many current American imprisonment practices are, they cannot be compared to the lethal sadism of criminal punishment in earlier centuries

Okay, true enough, but for me, this answer misses the point of the question. The underlying assumption behind the question seems to be “yes, violence might have declined, but isn’t locking up millions of people – six million to be exact – a number larger than those of Stalin’s gulag archipelago, 60 % of whom are there for nonviolent offenses, a form of violence?” Or perhaps “might the decline in violence be the result of mass imprisonment?” Admitting either would force Pinker to accept that the moral progress he details is perhaps not as unequivocal as he wants us to believe.

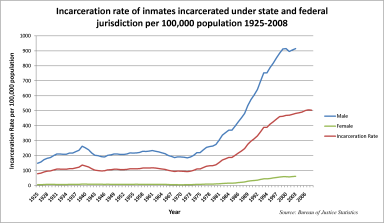

Here, I think, is where Pinker’s attachment to the Enlightenment idea of progress leads clearly to complacency. Pinker loves graphs, so here’s a graph:

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_incarceration_rate

It seems frankly obtuse to not connect the decline in crime with the sheer number of people now being locked up. It is tragic, but the connection between rising rates of imprisonment and declining crime rates can be seen even in Pinker’s vaunted Western Europe where the rate of imprisonment rose– though to nothing like the obscene rate it rose in the United States- and the crime rate fell in tandem.

Yet, unless the scale of imprisonment is put in context we are likely to see imprisonment of nonviolent offenders as less than morally problematic, and merely as an unfortunate consequence of the need to protect ourselves from violent crime by throwing the net of criminal justice as wide as it can be thrown, something Pinker seems to do when he states:

A regime that trawls for drug users or other petty delinquents will net a certain number of violent people as a by-catch, further thinning the ranks of the violent people who remain on the streets. (BA 122)

The strange thing here is that the uniquely American practice of locking up every law breaker without distinguishing between the risks posed by the accused is not only clearly disproportional and unjust it has makes no apparent effect on the actual rate of violent crime. The US incarcerates a whopping 743 persons per 100,00 whereas Great Britain lock up 154 per the same amount and the US still has an intentional homicide rate 4 times higher than in the UK.

By seeing modern history almost exclusively through the lens of moral progress, Pinker blinds himself to the question of whether or not our own age is engaged in practices that a more progressive future will regard with horror.

The question of imprisonment and its relationship to the decline of crime is not the only place where Pinker in his Better Angels of Our Nature dismisses a messy, often harsh, reality in the name of a simplified Enlightenment notion of progress. This can be seen in Pinker’s notions regarding contemporary slavery and war.

In a strange way, Pinker’s insistence that we recognize the reality of moral and social progress might short-circuit our capacity for progress in the future. You can see this in his treatment of “human trafficking” a modern day euphemism for slavery. As always, Pinker wants to let us know that current figures are exaggerated, as always, he reminds us that what we have here is no comparison to the far crueler reality of slavery found in the past. But this viewpoint comes at the cost of continuity. Anti-slavery advocates such as those of the organization Free the Slaves assume a moral continuity between themselves and the earlier abolition movements- and well they should. But Pinker’s rhetoric is less “we have almost reached the summit” than one of undermining the moral worth of their struggle with his damned proportionality- that things are better than ever now because “proportional to world population” not as many people are murdered, die in war, or are enslaved.

Numbers off or not- anywhere even in the ballpark of 25 million slaves today- the high estimate- still constitute an enormous amount of human suffering- such as innumerable rapes, beatings, and forced labor (no doubt Pinker would try to put a number on them)- suffering Pinker does not explore.

What holds for slavery in Better Angels holds for war as well. He is at pains to point out the casualty figures of the most savage conflict of the last generation- a conflict most westerners have probably not even heard about- The Great War of Africa– are grossly exaggerated, that the war only killed 1.5 million- not the 5 million human beings often reported.

Pinker’s right about one thing- wars between the world’s most powerful states have, at least for the moment disappeared.Wars between the great powers have always been the greatest killers in history, and we haven’t had any of those since 1945, and the question is- why? Pinker will not allow the obvious answer to his question, namely, that the post 1945 era is the age of nuclear weapons, that for the first time in history, war between great powers meant inevitable suicide. His evidence against the “nuclear peace” is that more nations have abandoned nuclear weapons programs than have developed such weapons. The fact is perhaps surprising but nonetheless accurate. It becomes a little less surprising, and a little less encouraging in Pinker’s sense, when you actually look at the list of countries who have abandoned them and why. Three of them: Belarus, Kazakhstan and the Ukraine are former Soviet republics and were under enormous Russian and US pressure- not to mention financial incentives- to give up their weapons after the fall of the Soviet Union. Two of them- South Africa and Libya- were attempting to escape the condition of being international pariahs. Another two- Iraq and Syria had their nuclear programs derailed by foreign powers. Three of them: Argentina, Brazil, and Algeria faced no external existential threat that would justify the expense and isolation that would come as a consequence of their development of nuclear weapons and five others: Egypt, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Germany were woven tightly into the US security umbrella.

Countries that face a perceived existential threat from a nuclear power or conventionally advanced power (and Argentina never faced an existential threat from Great Britain, that is Britain never threatened to conquer the county during the Falklands War) would appear to have a pretty large incentive to develop nuclear weapons insofar as they do not possess strong security guarantees from one of the great powers.

Pinker believes that Kant’s democratic peace theory (that democracies tied together by links of trade and international organization do not fight one another) helps explain the decline of war, but that does not explain why the US and Soviet Union did not go to war or India and Pakistan, or Taiwan and China, or South and North Korea. He pins his hopes on the normative change against nuclear weapons found in a Global Zero a movement that includes an eclectic group of foreign policy figures including realists such as Henry Kissinger that hopes to rid the world of nuclear weapons.

While I find the goal of a nuclear weapons free world laudable, the problem I see in this is that weaker powers lacking advanced conventional weapons could very well understand this movement as a way for the big powers to preserve the rationality of war. In fact, the worse thing imaginable would be for great power war to regain its plausibility. If the recent success of Israel’s “Iron Dome” is any indication we may end up there even without the world abandoning its nuclear weapons. Great powers, such as the US and China, may be more likely to engage in brinkmanship if they start to think they could survive a nuclear exchange. Recent confrontations between China and its neighbors and East Asia’s quite disturbing military buildup do not portend well for 21st century pacifism.

Global Zero might with tragic irony prove more dangerous that the current quite messy regime if it is not followed in parallel with an effort to solve the world’s outstanding disputes and to build a post- US- as- sole- superpower security architecture-not to mention efforts to limit conventional weapons which while we were sleeping have become just as deadly as nuclear weapons as well. Where everyone feels safe there is no need for everyone to be armed to the teeth.

Pinker recoils from messy explanations or morally ambiguous reality because he is wedded to the idea that the decline in violence was driven by a change in norms- a change that he thinks began with the Enlightenment. In his eyes, we are indeed morally superior to our predecessors in that we have a more inclusive and humane moral sense. Pinker turns to the ethical philosopher- Peter Singer- and his idea of the “escalator of reason” for a philosophical explanation of this normative change. Singer thinks that overtime human generations reason their way to inclusiveness and humanity by expanding our “circle of empathy”. Once only one’s close kin sat in the circle of concern, then fellow members of one’s state or faith, now perhaps all of humanity or, as Singer himself is most famous for in his Animal Liberation, the circle can be extended to non-human species.

Singer, however, is an odd duck to peg yourself to as a kind of philosophical backdrop for modern moral progress. A reader of Better Angels who did not know about Singer would be left unaware of just how controversial Singer’s views are. If memory serves me correctly, this fact that his views are something less than mainstream is tucked away in a footnote at the back of Pinker’s book.

Here is Singer from his Writings on an Ethical Life:

When the death of a disabled infant will lead to the birth of another infant with better prospects of a happy life, the total amount of happiness will be greater if the disabled infant is killed. (189)

I should be clear here that Singer is not talking about abortion, but infanticide, indeed he sees both practices as acceptable and morally equivalent:

That a fetus is known to be disabled is a widely accepted grounds for abortion. Yet in discussing abortion, we saw that birth does not mark a morally significant dividing line. I can not see how one could defend the view that fetuses may be “replaced” before birth, but newborn infants may not be” (191)

If this is the escalator of reason I want to get off.

Much as with the case with Foucault, Pinker doesn’t spend even a page or two engaging with these ideas. With 802 pages to its name a few more pages would seem a small price to pay, but again they are ignored, perhaps largely because they detract from Pinker’s Enlightenment notions of moral progress. Even briefly grappling with these ideas, for me at least, seems to lead to all sorts of interesting and often quite disturbing possibilities that are outside the simplistic dichotomies of progress and anti-progress set up but Pinker and Foucault.

Our society has certainly made progress morally over past ages in its abolition of torture and slavery, in it’s extension of rights to the formerly oppressed , its inclusion of women in political, economic and intellectual life, its freedom of speech and thought,

not to mention the vast increases in our standards of living, and yet…

May be our society has not so much progressed morally in the sense of empathy as it has become squeamish about violence, and physical coercion (real violence that is- media and video games seem to reveal an obsessive bloodlust). What we have done is managed to effectively conceal violence, and wherever possible to have adopted social and psychological methods of manipulation and control- including surveillance– in place of, to use military speak, “kinetic” methods. Our factory farms kill and confine more animals than have ever suffered such a fate- only we never see it. (Perhaps that is part of the explanation for why our urbanizing world has become so squeamish about violence, the fact that so few of us are engaged in the violence against animals found in agricultural life). We do not physically torture but confine and conceal far more persons than were ever caught in the cruel but paltry nets of pre-modern states. Chattel slavery and its savagery are a thing of the past, but what we have now are millions of invisible slaves, kidnapped, locked in houses, people who are our very neighbors suffering the cruel tyranny of one human being over another.

Our wars are fought in regions deemed too dangerous to be covered by mainstream media and our images of them sanitized for prime-time viewing. Our bloated and growing militaries represent bottled up potential energy that could level whole civilizations, indeed destroy the human species and the earth, should circumstances ever sweep us up and call it to burst forth. Yet, even our soldiers are averse to killing, so we are building machines capable of murdering more effectively and without conscience to replace them.

We do not expose our newborns on the rocks because they are girls or are disabled, but select against them in the womb so that 100 million girls have “gone missing” and whole categories of human beings are disappearing from the world, and some, such as the geneticist Julian Savulescu argue it is our “moral duty” to perform this “redesign” of the human species.

This returns me to the critic Merquior. Merquior makes the valid critique of Foucault that he is a sloppy historian, that he wants history to neatly fit his theory, which history can never do. Above all Merquior sees the flaws in Foucault’s argument stemming from his a prior position that the Enlightenment was less a humanitarian than a proto-totalitarian movement. This makes it impossible for Foucault to see the movement against torture and the creation of the modern prison system as anything more that an expression of a Nietzschean “will to power”.

But Merquior asks:

Why should the historian choose between the angelic image of a demo-liberal bourgeois order, unstained by class domination, and the hellish picture of ubiquitous coercion? Is not the actual historical record a mixed one, showing real libertarian and equalizing trends besides several configurations of class power and coercive cultural traits? (98)

Pinker might have done better had he employed Merquior’s critique of Foucault to himself, for, by seeing in modern developments the hand of progress from savagery to civilization, Pinker ends up blinding himself to the more complex historical picture as much as Foucault who saw in modern trends little but the move towards social totalitarianism. Indeed, Pinker could save his Better Angels by adding just one chapter as an afterward. The chapter would look at not where we have come from, but where we are and the struggles still left to us. It would provide a human face to the modern day suffering of those in our progressive age who are still enslaved and who continue to be killed and maimed by war. Those murdered and raped and those suffering behind bars for crimes that have harmed no one but themselves and those who love them. It would be a face Pinker had taken from them by turning them into numbers. It would seek to locate and avoid the many cliffs that might just plunge us downward, and say to all of us “we have just a little ways to go, but for the sake of our own enlightened legacy, we must have the forward thinking and endurance to climb onward, and above all, not to fall.”