Readers of this blog who take note of how much I talk about the Book of Revelation might be forgiven for thinking I had perhaps lost my grip on reality, that soon I might be found wandering the street with a sign around my neck informing the world that “the end is near!” or might be on the verge of joining the church of Harold Camping with the hope that next time he will get his dates right.

Of course, nothing could be further from the truth. Nevertheless, I perhaps find the Book of Revelation as fascinating as those who believe it to be an outline of the human future composed by the mind of God. For me, Revelation is the first, and without doubt the most powerful dystopia ever written. The vagueness of its symbolism is its strength. For what other narrative is so flexible that its penultimate villain- the Anti-Christ- can be grafted onto historical figures as diverse as the Roman Emperor Nero, Pope Boniface VIII, Napoleon Bonaparte, Abraham Lincoln, and Barack Obama.

We should not forget either that the Revelation narrative was sometimes used by the “good guys” of history such as Bartolome de Las Casas who fought for the rights of Native Americans against his Spanish countrymen, or could be found in the hearts and minds of the Union armies during the Civil War who sang:

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord:

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He hath loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword:

His truth is marching on.

He is coming like the glory of the morning on the wave,

He is Wisdom to the mighty, He is Succour to the brave,

So the world shall be His footstool, and the soul of Time His slave,

Our God is marching on.

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Revelation has proven the most powerful dystopian narrative in history whose value is as varied as the humanity that is its subject inspiring saints, poets, madmen and murderers. Thus, I awaited with some anticipation to get my hands on the religious scholar Elaine Pagels’ recently released Revelations: Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation. Pagels is a brilliant historian of religion who writes in a style accessible to the lay reader, and in her work she sets out to tell us the origins of this strangest of books.

For those who have never read the Book of Revelation, or have read it and don’t quite remember what exactly it says, below are the basics. Please bear with it, for later on, with the help of Pagel we will snap the whole thing into place.

The author of Revelation , John of Patmos, announces at the beginning of his book in a tone that clearly implies the imminent occurrence of what he is about to unveil:

Blessed is he that readeth, and they that hear the words of this prophecy, and keep those things therein: for the time is at hand. [emphasis added]

In powerful words John speaks in the voice of God and indicates that the story he will tell is the end of a drama that began with the creation:

I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the ending, saith the Lord, which is, what was, and which is to come, the Almighty.

John then reports how he was given his prophecy, which come to him in visions that he was told by God to convey by letters along with “warnings” to the seven churches of Asia.

In his letter to the church of Ephesus John warns against “them which say they are apostles and are not”. To the church of Smyrna he warns against “those who say they are Jews and are not”. The church of Pergamos he warns against worshipers of the pagan god Baal. Thyatira he warns against “that woman Jezebel who calleth herself a prophet”. Sardis he cautions to keep on the right path. To Philadelphia John again makes this strange warning against those “which say they are Jews and are not” but are instead of “the synagogue of Satan”. [Quick note: this has often been interpreted as deranged anti-semitism on the part of John, and that is how I have always read it, but Pagel is going to offer a whole new explanation for this nonsense, so again, stay turned]. Lastly, John warns the Laodiceans about their “lukewarm” faith.

Now the story gets interesting. John sees four heavenly beasts with the faces of a lion, calf, man, and an eagle each with six wings and “full of eyes within” surrounding a throne on a “sea of glass” praising God. Around the throne also are seated 24 “elders” clothed in dazzling white and also singing praises to God.

On his throne, God holds a book in right hand locked shut with “seven seals”, only a slain lamb, the symbol of Christ, is able to open the book. This is the book on which the end of our world is written. The breaking of the first seal brings forth a white horse representing conquest, the second a red horse-violence-, a black horse-famine-, and a white horse-death. The breaking of the fifth seal reveals those who have died in the name of their faith who cry for the justice and revenge of God upon their tormentors.

The sixth seal triggers an enormous earthquake, the sun goes black, the moon becomes as red as blood, and stars fall from the sky.

For the great day of his wrath has come; and who shall be able to stand?

Angels descend from heaven to mark God’s chosen with a seal that will offer them protection from the horrors to come 144,000 are so marked. The story gets even harder to follow. At the breaking of the seventh seal angel’s blow trumpets and all hell breaks-loose, so to speak, the angles pour out vials causing all kinds of horrors and monsters to descend upon the earth where a gaping abyss has opened up.

John now shatters all human conventions of past, present, and future. He sees a woman in heaven bathed in sunlight crying in labor giving birth to a child. (Mary, giving birth to Jesus which had happened a little less than a century before John wrote) Satan, emerging from the abyss, makes chase to kill the child and battles Michael and the Angels of heaven (something that “took place” before the creation of mankind). To his side Satan calls the two figures we all remember from Revelation, the Beast, and another figure who has become known as the Antichrist.

The Beast has “seven heads and ten horns” and is obviously some sort of political power for he is said to have power “over all kindreds and tongues and nations”. The Beast has been “wounded by a sword but did live”. The second figure, the Antichrist, makes his appearance. He is a sort of miracle worker who convinces the masses to worship the first Beast. The Antichrist decrees that everyone:

….. receive a mark in their right hand or in their forehead:

and that no man might buy or sell, save that he had the mark, or the name of the beast, or the number of his name.

John then let’s us know that if we are wise enough we can actually figure out who this beast is:

for it is the number of a man: and his number is six-hundred threescore and six.

John then sees seven more angels pour yet more cups of horrors on the peoples of the earth. One of these angels takes John to see a woman sitting on a scarlet colored beast- again with seven heads. Upon her head is written:

MYSTERY BABYLON THE GREAT, THE MOTHER OF HARLOTS AND ABOMINATIONS OF THE EARTH

And we are informed that the seven heads of the beast “are seven mountains, on which the woman sitteth”.

John tells us how Babylon will be destroyed and how the merchants that have grown rich from her and those that have felt her pleasures “cinnamon, and, and ointments, and frankincense, and wine, and oil… and the souls of men” [emphasis added] will lament her fall.

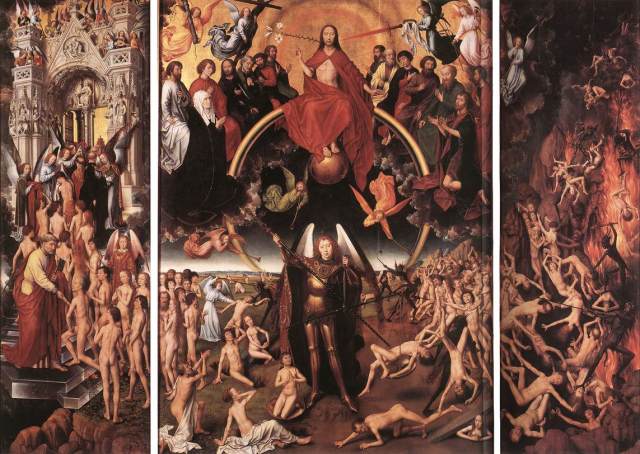

God, on a white horse, and his armies descend from heaven and destroy the Beast, and end up chaining Satan in a bottomless pit for a thousand years. After this period Satan is released who will again deceive the nations of the earth including “Gog and Magog” at the four corners of the earth. A last great battle for the meaning of the world ensues. The forces of good win. The great generations of the dead of humanity rise from under water and earth: their physical bodies reconstituted. The wicked of the world receive God’s justice, condemned to a lake of fire.

After this last epic battle between the forces of good and evil, the resurrection of the dead and last judgement, John’s prophecy turns from a horrifying dystopian vision to poetic image of utopia, a reality that promises moral closure, a final end in which the world has made sense: the evil punished, the good rewarded, and all that haunts us has passed away. The world as we have known it with its deceit, desire, pain, and suffering is at last gone replaced with something entirely new and beautiful:

And God will wipe away all the tears from their eyes: and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any pain: for the former things are passed away.

The holy city of Jerusalem, the seat of this new world, is composed of dazzling jewels on a sea of glass.

And the city had no need of the sun, neither of the moon… for the Lord God giveth them light and they shall reign forever and ever.

That then, is the Book of Revelation, we are left with questions: Who was this John of Patmos? Why did he write this strange book that has haunted us since? What does its crazy symbolism: this Beast, and Antichrist, and Jezebel, and Babylon and all the rest mean? And lastly, the most important questions, what does it say to us? What does it mean, for us?

We will need Pagels’ help to answer these questions, and I will pick it up there next time.