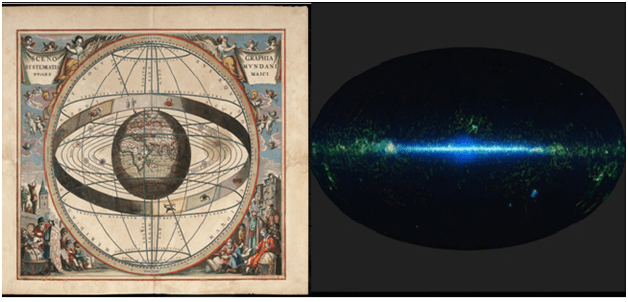

The one rule that seems to hold for everything in our Universe is that all that exists, after a time, must pass away, which for life forms means they will die. From there, however, the bets are off and the definition of the word “time” in the phrase “after a time” comes into play. The Universe itself may exist for as long as 100s of trillions of years to at last disappear into the formless quantum field from whence it came. Galaxies, or more specifically, clusters of galaxies and super-galaxies, may survive for perhaps trillions of years to eventually be pulled in and destroyed by the black holes at their centers.

Stars last for a few billion years and our own sun some 5 or so billion years in the future will die after having expanded and then consumed the last of its nuclear fuel. The earth having lasted around 10 billion years by that point will be consumed in this expansion of the Sun. Life on earth seems unlikely to make it all the way to the Sun’s envelopment of it and will likely be destroyed billions of years before the end of the Sun- as solar expansion boils away the atmosphere and oceans of our precious earth.

The lifespan of even the oldest lived individual among us is nothing compared to this kind of deep time. In contrast to deep time we are, all of us, little more than mayflies who live out their entire adult lives in little but a day. Yet, like the mayflies themselves who are one of the earth’s oldest existent species: by the very fact that we are the product of a long chain of life stretching backward we have contact with deep time.

Life on earth itself if not quite immortal does at least come within the range of the “lifespan” of other systems in our Universe, such as stars. If life that emerged from earth manages to survive and proves capable of moving beyond the life-cycle of its parent star, perhaps the chain in which we exist can continue in an unbroken line to reach the age of galaxies or even the Universe itself. Here then might lie something like immortality.

The most likely route by which this might happen is through our own species, Homo Sapiens or our descendents. Species do not exist forever, and our is likely to share this fate of demise either through actual extinction or evolution into something else. In terms of the latter, one might ask if our survival is assumed, how far into the future we would need to go where our descendents are no longer recognizably, human? As long as something doesn’t kill us, or we don’t kill ourselves off first, I think that choice, for at least the foreseeable future will be up to us.

It is often assumed that species have to evolve or they will die. A common refrain I’ve heard among some transhumanists is “evolve or die!”. In one sense, yes, we need to adapt to changing circumstances, in another, no, this is not really what evolution teaches us, or is not the only thing it teaches us. When one looks at the earth’s longest extant species what one often sees is that once natural selection comes us with a formula that works that model will be preserved essentially unchanged over very long stretches of time, even for what can be considered deep time. Cyanobacteria are nearly as old as life on earth itself, and the more complex Horseshoe Crab, is essentially the same as its relatives that walked the earth before the dinosaurs. The exact same type of small creatures that our children torture on beach vacations might have been snacks for a baby T-Rex!

That was the question of the longevity of species but what about the longevity of individuals? Anyone interested the should check out the amazing photo study of the subject by the artist Rachel Sussman. You can see Sussman’s work here at TED, and over at Long Now. The specimen Sussman brings to light have individuals over 2,000 years old. Almost all are bacteria or plants and clonal- that is they exist as a single organism composed of genetically identical individuals linked together by common root and other systems. Plants and especially trees are perhaps the most interesting because they are so familiar to us and though no plant can compete with the longevity of bacteria, a clonal colony of Quaking Aspen in Utah is an amazing 80,000 years old!

The only animals Sussman deals with are corals, an artistic decision that reflects the fact that animals do not survive for all that long- although one species of animal she does not cover might give the long-lifers in the other kingdoms a run for their money. The “immortal jellyfish” the turritopsis nutricula are thought to be effectively biologically immortal (though none are likely to have survived in the wild for anything even approaching the longevity of the longest lived plants). The way they achieve this feat is a wonder of biological evolution.The turritopsis nutricula, after mating upon sexual maturity, essentially reverses it own development process and reverts back to prior clonal state.

Perhaps we could say that the turritopsis nutricula survives indefinitely by moving between more and less complex types of structures all the while preserving the underlying genes of an individual specimen intact. Some hold out the hope that the turritopsis nutricula holds the keys to biological immortality for individuals, and let’s hope they’re right, but I, for one, think its lessons likely lie elsewhere.

A jellyfish is a jellyfish, after all, among more complex animals with well developed nervous systems longevity moves much closer to a humanly comprehensible lifespan with the oldest living animal a giant tortoise by the too cute name of “Jonathan” thought to be around 178 years old. This is still a very long time frame in human terms, and perhaps puts the briefness of our own recent history in perspective: it would be another 26 years after Jonathan hatched from his egg till the first shots of the American Civil War were fired. A lot can happen over the life of a “turtle”.

Individual plants, however, put all individual animals to shame. The oldest non-clonal plant, The Great Basin Bristlecone Pine, has a specimen believed to be 5,062 years old. In some ways this oldest living non-clonal individual is perfectly illustrative of the (relatively) new way human beings have reoriented themselves to time, and even deep time.When this specimen of pine first emerged from a cone human beings had only just invented a whole set of tools that would make the transmission of cultural rather than genetic information across vast stretches of time possible. During the 31st century B.C.E. we invented monumental architecture such as Stonehenge and the pyramids of Egypt whose builders still “speak” to us, pose questions to us, from millennia ago. Above all, we invented writing which allowed someone with little more than a clay tablet and a carving utensil to say something to me living 5,000 years in his future.

Humans being the social animals that they are we might ask ourselves about the mortality or potential immortality of groups that survive across many generations, and even for thousands of years. Group that survive for such a long period of time seem to emerge most fully out of the technology of writing which allows both the ability to preserve historical memory and permits a common identity around a core set of ideas. The two major types of human groups based on writing are institutions, and societies which includes not just the state but also the economic, cultural, and intellectual features of a particular group.

Among the biggest mistakes I think those charged with responsibility for an institution or a society can make is to assume that it is naturally immortal, and that such a condition is independent of whatever decisions and actions those in charge of it take. This was part of the charge Augustine laid against the seemingly eternal Roman Empire in his The City of God. The Empire, Augustine pointed out, was a human institution that had grown and thrived from its virtues in the past just as surely as it was in his day dying from its vices. Augustine, however, saw the Church and its message as truly eternal. Empires would come and go but the people of God and their “city” would remain.

It is somewhat ironic, therefore, that the Catholic Church, which chooses a Pope this week, has been so beset by scandal that its very long-term survivability might be thought at stake. Even seemingly eternal institutions, such as the 2,000 year old Church, require from human beings an orientation that might be compared to the way theologians once viewed the relationship of God and nature. Once it was held that constant effort by God was required to keep the Universe from slipping back into the chaos from whence it came. That the action of God was necessary to open every flower. While this idea holds very little for us in terms of our understanding of nature, it is perhaps a good analog for human institutions, states and our own personal relationships which require our constant tending or they give way to mortality.

It is perhaps difficult for us to realize that our own societies are as mortal as the empires of old, and someday my own United States will be no more. America is a very odd country in respect to its’ views of time and history. A society seemingly obsessed with the new and the modern, contemporary debates almost always seek reference and legitimacy on the basis of men who lived and thought over 200 years ago. The Founding Fathers were obsessed with the mortality of states and deliberately crafted a form of government that they hoped might make the United States almost immortal.

Much of the structure of American constitutionalism where government is divided into “branches” which would “check and balance” one another was based on a particular reading of long-lived ancient systems of government which had something like this tripart structure, most notably Sparta and Rome. What “killed” a society, in the view of the Founders, was when one element- the democratic, oligarchic-aristocratic, or kingly rose to dominate all others. Constitutionally divided government was meant to keep this from happening and therefore would support the survival of the United States indefinitely.

Again, it is somewhat bitter irony that the very divided nature of American government that was supposed to help the United States survive into the far future seems to be making it impossible for the political class in the US to craft solutions to the country’s quite serious long-term problems and therefore might someday threaten the very survival of the country divided government was meant to secure.

Anyone interested in the question of the extended survival of their society, indeed of civilization itself, needs to take into account the work of Joseph A. Tainter and his The Collapse of Complex Societies (1988). Here, the archaeologist Tainter not only provides us with a “science” that explains the mortality of societies, his viewpoint, I think, provides us for ways to think about and gives us insight into seeming intractable social and economic and technological bottlenecks that now confront all developed economies: Japan, the EU/UK and the United States.

Tainter, in his Collapse wanted to move us away from vitalist ideas of the end of civilization seen in thinkers such as Oswald Spengler and Arnold Toynbee. We needed, in his view, to put our finger on the material reality of a society to figure out what conditions most often lead them to dissipate i.e. to move from a more complex and integrated form, such as the Roman Empire, to a more simple and less integrated form, such as the isolated medieval fiefdoms that followed.

Grossly oversimplified, Tainter’s answer was a dry two word concept borrowed from economics- marginal utility. The idea is simple if you think about it for a moment. Any society is likely to take advantage of “low-hanging fruit” first. The best land will be the first to be cultivated, the easiest resources to gain access to exploited.

The “fruit”, however, quickly becomes harder to pick- problems become harder for a society to solve which leads to a growth in complexity. Romans first tapped tillable land around the city, but by the end of the Empire the city needed a complex international network of trade and political control to pump grain from the distant Nile Valley into the city of Rome.

Yet, as a society deploys more and more complex solutions to problems it becomes institutionally “heavy” (the legacy of all the problems it has solved in the past) just as problems become more and more difficult to solve. The result is, at some point, the shear amount of resources that need to be thrown at a problem to solve it are no longer possible and the only lasting solution becomes to move down the chain of complexity to a simpler form. Roman prosperity and civilization drew in the migration of “barbarian” populations in the north whose pressures would lead to the splitting of the Empire in two and the eventual collapse of its Western half.

It would seem that we have broken through Tainter’s problem of marginal utility with the industrial revolution, but we should perhaps not judge so fast. The industrial revolution and all of its derivatives up to our current digital and biological revolutions, replaced a system in which goods were largely produced at a local level and communities were largely self-sufficient, with a sprawling global network of interconnections and coordinated activities requiring vast amounts of specialized knowledge on the part of human beings who, by necessity, must participate in this system to provide for their most basic needs.

Clothes that were once produced in the home of the individual who would wear them, are now produced thousands of miles away by workers connected to a production and transportation system that requires the coordination of millions of persons many of whom are exercising specialized knowledge. Food that was once grown or raised by the family that consumed it now requires vast systems of transportation, processing, the production of fertilizers from fossil fuels and the work of genetic engineers to design both crops and domesticated animals.

This gives us an indication of just how far up the chain of complexity we have moved, and I think leads inevitably to the questions of whether such increasing complexity might at some point stall for us, or even be thrown into reverse?

The idea that, despite all the whiz-bang! of modern digital technology, we have somehow stalled out in terms of innovation is an idea that has recently gained traction. There was the argument made by the technologist and entrepreneur, Peter Thiel, at the 2009 Singularity Summit, that the developed world faced real dangers of the Singularity not happening quickly enough. Thiel’s point was that our entire society was built around the expectations of exponential technological growth that showed ominous signs of not happening. I only need to think back to my Social Studies textbooks in the 1980s and their projections of the early 2000s with their glittering orbital and underwater cities, both of which I dreamed of someday living in, to realize our futuristic expectations are far from having been met. More depressingly, Thiel points out how all of our technological wonders have not translated into huge gains in economic growth and especially have not resulted in any increase in median income which has been stagnant since the 1970s.

In addition to Theil, you had the economist, Tyler Cowen, who in his The Great Stagnation (2011) argued compellingly that the real root of America’s economic malaise was that the kinds of huge qualitative innovations that were seen in the 19th and early 20th centuries- from indoor toilets, to refrigerators, to the automobile, had largely petered out after the low hanging fruit- the technologies easiest to reach using the new industrial methods- were picked. I may love my iPhone (if I had one), but it sure doesn’t beat being able to sanitarily go to the bathroom indoors, or keep my food from rotting, or travel many miles overland on a daily basis in mere minutes or hours rather than days.

One reason why technological change is perhaps not happening as fast as boosters such as singularitarians hope, or our society perhaps needs to be able to continue to function in the way we have organized it, can be seen in the comments of the technologists, social critic and novelist, Ramez Naam. In a recent interview for The Singularity Weblog, Naam points out that one of the things believers in the Singularity or others who hold to ideas regarding the exponential pace of technological growth miss is that the complexity of the problems technology is trying to solve are also growing exponentially, that is problems are becoming exponentially harder to solve. It’s for this reason that Naam finds the singularitarians’ timeline widely optimistic. We are a long long way from understanding the human brain in such a way that it can be replicated in an AI.

The recent proposal of the Obama Administration to launch an Apollo type project to understand the human brain along with the more circumspect, EU funded, Human Brain Project /Blue Brain Project might be seen as attempts to solve the epistemological problems posed by increasing complexity, and are meant to be responses to two seemingly unrelated technological bottlenecks stemming from complexity and the problem of increasing marginal returns.

On the epistemological front the problem seems to be that we are quite literally drowning in data, but are sorely lacking in models by which we can put the information we are gathering together into working theories that anyone actually understands. As Henry Markham the founder of the Blue Brain Project stated:

So yes, there is no doubt that we are generating a massive amount of data and knowledge about the brain, but this raises a dilemma of what the individual understands. No neuroscientists can even read more than about 200 articles per year and no neuroscientists is even remotely capable of comprehending the current pool of data and knowledge. Neuroscientists will almost certainly drown in data the 21st century. So, actually, the fraction of the known knowledge about the brain that each person has is actually decreasing(!) and will decrease even further until neuroscientists are forced to become informaticians or robot operators.

This epistemological problem, which was brilliantly discussed by Noam Chomsky in an interview late last year is related to the very real bottleneck in Artificial Intelligence- the very technology Peter Thiel thinks is essentially if we are to achieve the rates of economic growth upon which our assumptions of technological and economic progress depend.

We have developed machines with incredible processing power, and the digital revolution is real, with amazing technologies just over the horizon. Still, these machines are nowhere near doing what we would call “thinking”. Or, to paraphrase the neuroscientist and novelist David Eagleman- the AI WATSON might have been able to beat the very best human being in the game Jeopardy! What it could not do was answer a question obvious to any two year old like “When Barack Obama enters a room, does his nose go with him?”

Understanding how human beings think, it is hoped, might allow us to overcome this AI bottleneck and produce machines that possess qualities such as our own or better- an obvious tool for solving society’s complex problems.

The other bottleneck a large scale research project on the brain is meant to solve is the halted development of psychotropic drugs– a product of the enormous and ever increasing costs for the creation of such products. Itself a product of the complexity of the problem pharmaceutical companies are trying to tackle, namely; how does the human brain work and how can we control its functions and manage its development? This is especially troubling given the predictable rise in neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s. It is my hope that these large scale projects will help to crack the problem of the human brain, and especially as it pertains to devastating neurological disorders, let us pray they succeed.

On the broader front, Tainter has a number of solutions that societies have come up with to the problem of marginal utility two of which are merely temporary and the other long-term. The first is for society to become more complex, integrated, bigger. The old school way to do this was through conquest, but in an age of nuclear weapons and sophisticated insurgencies the big powers seem unlikely to follow that route. Instead what we are seeing is proposals such as the EU-US free trade area and the Trans-Pacific partnership both of which appear to assume that the solution to the problems of globalization is more globalization. The second solution is for a society to find a new source of energy. Many might have hoped this would have come in the form of green-energy rather than in the form it appears to have taken- shale gas, and oil from the tar sands of Canada. In any case, Tainter sees both of these solutions as but temporary respites for the problem of marginal utility.

The only long lasting solution Tainter sees for increasing marginal utility is for a society to become less complex that is less integrated more based on what can be provided locally than on sprawling networks and specialization. Tainter wanted to move us away from seeing the evolution of the Roman Empire into the feudal system as the “death” of a civilization. Rather, he sees the societies human beings have built to be extremely adaptable and resilient. When the problem of increasing complexity becomes impossible to solve societies move towards less complexity. It is a solution that strangely echoes that of the “immortal jellyfish” the turritopsis nutricula, the only path complex entities have discovered that allows them to survive into something that whispers eternity.