There has been some ink spilt lately at the IEET over a new movement that goes by the Tolkienesque name, I kid you not, of the dark enlightenment also called neo-reactionaries. Khannea Suntzu has looked at the movement from the standpoint of American collapse and David Brin within the context of a rising oligarchic neo-feudalism.

I have my own take on the neo-reactionary movement somewhat distinct from that of either Suntzu or Brin, which I will get to below, but first a recap. Neo-reactionaries are a relatively new group of thinkers on the right that in general want to abandon the modern state, built such as it is around the pursuit of the social welfare, for lean-and-mean governance by business types who know in their view how to make the trains run on time. They are sick of having to “go begging” to the political class in order to get what they want done. They hope to cut out the middle-man. It’s obvious that oligarchs run the country so why don’t we just be honest about it and give them the reins of power? We could even appoint a national CEO- if the country remains in existence- we could call him the king. Oh yeah, on top of that we should abandon all this racial and sexual equality nonsense. We need to get back to the good old days when the color of a man’s skin and having a penis really meant something- put the “super” back in superior.

At first blush the views of those hoping to turn the lights out on enlightenment (anyone else choking on an oxymoron) appear something like those of the kind of annoying cousin you try to avoid at family reunions. You know, the kind of well off white guy who thinks the Civil Rights Movement was a communist plot, calls your wife a “slut” (their words, not mine) and thinks the real problem with America is that we give too much to people who don’t have anything and don’t lock up or deport enough people with skin any darker than Dove Soap. Such people are the moral equivalent of flat-earthers with no real need to take them seriously, though they can make for some pretty uncomfortable table conversation and are best avoided like a potato salad that has been out too long in the sun.

What distinguishes neo-reactionaries from run of the mill ditto heads or military types with a taste for Dock Martins or short pants is that they tend to be latte drinking Silicon Valley nerds who have some connection to both the tech and trans-humanist communities.

That should get this audience’s attention.

To continue with the analogy from above: it’s as if your cousin had a friend, let’s just call him totally at random here… Peter Thiel, who had a net worth of 1.5 billion and was into, among other things, working closely with organizations such as the NSA through a data mining firm he owned- we’ll call it Palantir (damned Frodo Baggins again!) and who serves as a deep pocket for groups like the Tea Party. Just to go all conspiracy on the thing let’s make your cousin’s “friend” a sitting member on something we’ll call The Bilderberg Group a secretive cabal of the world’s bigwigs who get together to talk about what they really would like done in the world. If that was the case the last thing you should do is leave your cousin ranting to himself while you made off for another plate of Mrs. T’s Pierogies. You should take the maniac seriously because he might just be sitting on enough cash to make his atavistic dreams come true and put you at risk of sliding off a flattened earth.

All this might put me at risk of being accused of lobbing one too many ad hominem, so let me put some meat on the bones of the neo-reactionaries. The Super Friends or I guess it should be Legion of Doom of neo-reaction can be found on the website Radish where the heroes of the dark enlightenment are laid out in the format of Dungeons and Dragons or Pokémon cards (I can’t make this stuff up). Let’s just start out with the most unfunny and disturbing part of the movement- its open racism and obsession with the 19th century pseudo-science of dysgenics.

Here’s James Donald who from his card I take to be a dwarf, or perhaps an elf, I’m not sure what the difference is, who likes to fly on a winged tauntaun like that from The Empire Strikes Back.

To thrive, blacks need simpler, harsher laws, more vigorously enforced, than whites. The average black cannot handle the freedom that the average white can handle. He is apt to destroy himself. Most middle class blacks had fathers who were apt to frequently hit them hard with a fist or stick or a belt, because lesser discipline makes it hard for blacks to grow up middle class. In the days of Jim Crow, it was a lot easier for blacks to grow up middle class.

Wow, and I thought a country where one quarter of African American children will have experienced at least one of their parents behind bars– thousands of whom will die in prison for nonviolent offenses– was already too harsh. I guess I’m a patsy.

Non-whites aren’t the only ones who come in for derision by the neo-reactionaries a fact that can be summed up by the post- title of one of their minions, Alfred W. Clark, who writes the blog Occam’s Razor : Are Women Who Tan Sluts. There’s no need to say anything more to realize poor William of Occam is rolling in his grave.

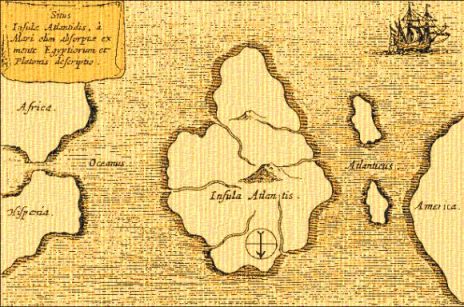

Beyond this neo-Nazism for nerds quality neo-reactionaries can make one chuckle especially when it comes to “policy innovations” such as bringing back kings.

Here’s modern day Beowulf Mencius Moldbug:

What is England’s problem? What is the West’s problem? In my jaundiced, reactionary mind, the entire problem can be summed up in two words – chronic kinglessness. The old machine is missing a part. In fact, it’s a testament to the machine’s quality that it functioned so long, and so well, without that part.

Yeah, that’s the problem.

Speaking of atavists, one thing that has always confused me about the Tea Party is that I have never been sure which imaginary “golden age” they wanted us to return to. Is it before desegregation? Before FDR? Prior to the creation of the Federal Reserve (1913)? Or maybe it’s back to the antebellum south? Or maybe back to the Articles of Confederation? Well, at least the neo-reactionaries know where they want to go- back before the American Revolution. Obviously since this whole democracy thing hasn’t worked out we should bring back the kings, which makes me wonder if these guys have mourning parties on Bastille Day.

Okay, so the dark voices behind neo-reaction are a bunch of racist/sexist nerds who have a passion for kings and like to be presented as characters on D&D cards. They have some potentially deep pockets, but other than that troubling fact why should we give them more than a few seconds of serious thought?

Now I need to exchange my satirical cap for my serious one for the issues are indeed serious. I think understanding neo-reaction is important for two reasons: they are symptomatic of deeper challenges and changes occurring politically, and they have appeared as a response to and on the cusp of a change in our relationship to Silicon Valley a region that has been the fulcrum point for technological, economic and political transformation over the past generation.

Neo-reaction shouldn’t be viewed in a vacuum. It has appeared at a time when the political and economic order we have had since at least the end of the Second World War which combines representative democracy, capitalist economics and some form of state supported social welfare (social democracy) is showing signs of its age.

If this was just happening in the United States whose 224 year old political system emerged before almost everything we take to be modern such as this list at random: universal literacy, industrialization, railroads, telephones, human flight, the Theory of Evolution, Psychoanalysis, Quantum Mechanics, Genetics, “the Bomb”, television, computers, the Internet and mobile technology then we might be able, as some have, to blame our troubles on an antiquated political system, but the creaking is much more widespread.

We have the upsurge in popularity of the right in Europe such as that seen in France with its National Front. Secessionist movements are gaining traction in the UK. The right in the form of Hindu Nationalism under a particular obnoxious figure- Narendra Modi -is poised to win Indian elections. There is the implosion of states in the Middle East such as Syria and revolution and counter revolution in Egypt. There are rising nationalist tensions in East Asia.

All this is coming against the backdrop of rising inequality. The markets are soaring no doubt pushed up by the flood of money being provided by the Federal Reserve, yet the economy is merely grinding along. Easy money is the de facto cure for our deflationary funk and pursued by all the world’s major central banks in the US, the European Union and now especially, Japan.

The far left has long abandoned the idea that 21st century capitalism is a workable system with the differences being over what the alternative to it should be- whether communism of the old school such as that of Slavoj Žižek or the anarchism of someone like David Graeber. Leftists are one thing the Pope is another, and you know a system is in trouble when the most conservative institution in history wants to change the status quo as Pope Francis suggested when he recently railed against the inhumanity of capitalism and urged for its transformation.

What in the world is going on?

If your house starts leaning there’s something wrong with the foundation, so I think we need to look at the roots of our current problems by going back to the gestation of our system- that balance of representative democracy, capitalism and social democracy I mentioned earlier whose roots can be found not in the 20th century but in the century prior.

The historical period that is probably most relevant for getting a handle on today’s neo-reactionaries is the late 19th century when a rage for similar ideas infected Europe. There was Nietzsche in Germany and Dostoevsky in Russia (two reactionaries I still can’t get myself to dislike both being so brilliant and tragic). There was Maurras in France and Pareto in Italy. The left, of course, also got a shot of B-12 here as well with labor unions, socialist political parties and seriously left-wing intellectuals finally gaining traction. Marxism whose origins were earlier in the century was coming into its own as a political force. You had writers of socialist fiction such as Edward Bellamy and Jack London surging in popularity. Anarchists were making their mark, though, unfortunately, largely through high profile assassinations and bomb throwing. A crisis was building even before the First World War whose centenary we will mark next year.

Here’s historian JM Roberts from his Europe 1880-1945 on the state of politics in on the eve, not after, the outbreak of the First World War.

Liberalism had institutionalized the pursuit of happiness, yet its own institutions seemed to stand in the way of achieving the goal; liberal’s ideas could, it seemed, lead liberalism to turn on itself.

…the practical shortcomings of democracy contributed to a wave of anti-parliamentarianism. Representative institutions had for nearly a century been the shibboleth of liberalism. An Italian sociologist now stigmatized them ‘as the greatest superstition of modern times.’ There was violent criticism of them, both practical and theoretical. Not surprisingly, this went furthest in constitutional states where parliamentary institutions were the formal framework of power but did not represent social realities. Even where parliaments (as in France or Great Britain) had already shown they possessed real power, they were blamed for representing the wrong people and for being hypocritical shams covering self-interest. Professional politicians- a creation of the nineteenth century- were inevitably, it was said, out of touch with real needs.

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

Liberalism, by which Roberts means a combination of representative government and laissez faire capitalism- including free trade- was struggling. Capitalism had obviously brought wealth and innovation but also enormous instability and tensions. The economy had a tendency to rocket towards the stars only to careen earthward and crash leaving armies of the unemployed. The small scale capitalism of earlier periods was replaced by continent straddling bureaucratic corporations. The representative system which had been based on fleeting mobilization during elections or crises had yet to adjust to a situation where mass mobilization through the press, unions, or political groups was permanent and unrelenting.

The First World War almost killed liberalism. The Russian Revolution, Great Depression, rise of fascism and World War Two were busy putting nails in its coffin when the adoption of social democracy and Allied Victory in the war revived the corpse. Almost the entirety of the 20th century was a fight over whether the West’s hybrid system, which kept capitalism and representative democracy, but tamed the former could outperform state communism- and it did.

In the latter half of the 20th century the left got down to the business of extending the rights revolution to marginalized groups while the right fought for the dismantling of many of the restrictions that had been put on the capitalist system during its time of crisis. This modus vivendi between left and right was all well and good while the economy was growing and while the extension of legal rights rather than social rights for marginalized groups was the primary issue, but by the early 21st century both of these thrusts were spent.

Not only was the right’s economic model challenged by the 2008 financial crisis, it had nowhere left to go in terms of realizing its dreams of minimal government and dismantling of the welfare state without facing almost impossible electoral hurdles. The major government costs in the US and Europe were pensions and medical care for the elderly- programs that were virtually untouchable. The left too was realizing that abstract legal rights were not enough. Did it matter that the US had an African American president when one quarter of black children had experienced a parent in prison, or when a heavily African American city such as Philadelphia has a child poverty rate of 40%? Addressing such inequities was not an easy matter for the left let alone the extreme changes that would be necessary to offset rising inequality.

Thus, ironically, the problem for both the right and the left is the same one- that governments today are too weak. The right needs an at least temporarily strong government to effect the dismantling of the state, whereas the left needs a strong government not merely to respond to the grinding conditions of the economic “recovery”, but to overturn previous policies, put in new protections and find some alternative to the current political and economic order. Dark enlightenment types and progressives are confronting the same frustration while having diametrically opposed goals. It is not so much that Washington is too powerful as it is that the power it has is embedded in a system, which, as Mark Leibovich portrays brilliantly, is feckless and corrupt.

Neo-reactionaries tend to see this as a product of too much democracy, whereas progressives will counter that there is not enough. Here’s one of the princes of darkness himself, Nick Land:

Where the progressive enlightenment sees political ideals, the dark enlightenment sees appetites. It accepts that governments are made out of people, and that they will eat well. Setting its expectations as low as reasonably possible, it seeks only to spare civilization from frenzied, ruinous, gluttonous debauch.

Yet, as the experience in authoritarian societies such as Libya, Egypt and Syria shows (and even the authoritarian wonderchild of China is feeling the heat) democratic societies are not the only ones undergoing acute stresses. The universal nature of the crisis of governance is brought home in a recent book by Moisés Naím. In his The End of Power Naím lays out how every large structure in society: armies, corporations, churches and unions are seeing their power decline and are being challenged by small and nimble upstarts.

States are left hobbled by smallish political parties and groups that act as spoilers preventing governments from getting things done. Armies with budgets in the hundreds of billions of dollars are hobbled by insurgents with IEDs made from garage door openers and cell phones. Long-lived religious institutions, most notably the Catholic Church, are losing parishioners to grassroots preachers while massive corporations are challenged by Davids that come out of nowhere to upend their business models with a simple stone.

Naím has a theory for why this is happening. We are in the midst of what he calls The More, The Mobility and The Mentality Revolutions. Only the last of those is important for my purposes. Ruling elites are faced today with the unprecedented reality that most of their lessers can read. Not only that, the communications revolution which has fed the wealth of some of these elites has significantly lowered the barriers to political organization and speech. Any Tom, Dick and now Harriet can throw up a website and start organizing for or against some cause. What this has resulted in is a sort of Cambrian explosion of political organization, and just as in any acceleration of evolution you’re likely to get some pretty strange mutants- and so here we are.

Some on the left are urging us to adjust our progressive politics to the new distributed nature of power. The writer Steven Johnson in his recent Future Perfect: The case for progress in a networked age calls collaborative efforts by small groups “peer-to-peer networks”, and in them he sees a glimpse of our political past (the participatory politics of the ancient Greek polis and late medieval trading states) becoming our political future. Is this too “reactionary”?

Peer-to-peer networks tend to bring local information back into view. The fact that traditional centralized loci of power such as the federal government and national and international media are often found lacking when it comes to local knowledge is a problem of scale. As Jane Jacobs has pointed out , government policies are often best when crafted and implemented at the local level where differences and details can be seen.

Wikipedia is a good example of Johnson’s peer-to-peer model as is Kickstarter. In government we are seeing the spread of participatory budgeting where the local public is allowed to make budgetary decisions. There is also a relatively new concept known as “liquid democracy” that not only enables the creation of legislation through open-sourced platforms but allows people to “trade” their votes in the hopes that citizens can avoid information overload by targeting their vote to areas they care most about, and presumably for this reason, have the greatest knowledge of.

So far, peer-to-peer networks have been successful at revolt- The Tea Party is peer-to-peer as was Occupy Wall Street. Peer-to-peer politics was seen in the Move-ON movement and has dealt defeat to recent legislation such as SOPA. Authoritarian regimes in the Middle East were toppled by crowd sourced gatherings on the street.

More recently than Johnson’s book there is New York’s new progressive mayor- Bill de Blasio’s experiment with participatory politics with his Talking Transition Tent on Canal Street. There, according to NPR, New Yorkers can:

….talk about what they want the next mayor to do. They can make videos, post videos and enter their concerns on 48 iPad terminals. There are concerts, panels on everything from parks to education. And they can even buy coffee and beer.

Democracy, coffee and beer- three of my favorite things!

On the one hand I love this stuff, but me being me I can’t help but have some suspicions and this relates, I think, to the second issue about neo-reactionaries I raised above; namely, that they are reflecting something going on with our relationship to Silicon Valley a change in public perception of the tech culture and its tools from hero and wonderworker to villain and illusionist.

As I have pointed out elsewhere the idea that technology offered an alternative to the lumbering bureaucracy of state and corporations is something embedded deep in the foundation myth of Silicon Valley. The use of Moore’s Law as a bridge to personalized communication technology was supposed to liberate us from the apparatchiks of the state and the corporation- remember Apple’s “1984” commercial?

It hasn’t quite turned out that way. Yes, we are in a condition of hyper economic and political competition largely engendered by technology, but it’s not quite clear that we as citizens have gained rather than “power centers” that use these tools against one another and even sometimes us. Can anyone spell NSA?

We also went from innovation, and thus potential wealth, being driven by guys in their garages to, on the American scene, five giants that largely own and control all of virtual space: Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple and Micro-Soft with upstarts such as Instagram being slurped up like Jonah was by the whale the minute they show potential growth.

Rather than result in a telecommuting utopia with all of us working five hours a day from the comfort of our digitally connected home, technology has led to a world where we are always “at work”, wages have not moved since the 1970’s and the spectre of technological unemployment is on the wall. Mainstream journalists such as John Micklethwait of The Economist are starting to see a growing backlash against Silicon Valley as the public becomes increasingly estranged from digerati who have not merely failed to deliver on their Utopian promises, but are starving the government for revenue as they hide their cash in tax havens all the while cosying up to the national security state.

Neo-reactionaries are among the first of Silicon Valleians to see this backlash building hence their only half joking efforts to retreat to artificial islands or into outer space. Here is Balaji Srinivasan whose speech was transcribed by one of the dark illuminati who goes by the moniker Nydwracu:

The backlash is beginning. More jobs predicted for machines, not people; job automation is a future unemployment crisis looming. Imprisoned by innovation as tech wealth explodes, Silicon Valley, poverty spikes… they are basically going to try to blame the economy on Silicon Valley, and say that it is iPhone and Google that done did it, not the bailouts and the bankruptcies and the bombings, and this is something which we need to identify as false and we need to actively repudiate it.

Srinivasan would have at least some things to use in defense of Silicon Valley: elites there have certainly been socially conscious about global issues. Where I differ is on their proposed solutions. As I have written elsewhere, Valley bigwigs such as Peter Diamandis think the world’s problems can be solved by letting the technology train keep on rolling and for winners such as himself to devote their money and genius to philanthropy. This is unarguably a good thing, what I doubt, however, is that such techno-philanthropy can actually carry the load now held up by governments while at the same time those made super rich by capitalism’s creative destruction flee the tax man leaving what’s left of government to be funded on the backs of a shrinking middle class.

As I have also written elsewhere the original generation of Silicon Valley innovators is acutely aware of our government’s incapacity to do what states have always done- to preserve the past, protect the the present and invest in the future. This is the whole spirit behind the saint of the digerati Stewart Brand’s Long Now Foundation in which I find very much to admire. The neo-reactionaries too have latched upon this short term horizon of ours, only where Brand saw our time paralysis in a host of contemporary phenomenon, neo-reactionaries think there is one culprit- democracy. Here again is dark prince Nick Land:

Civilization, as a process, is indistinguishable from diminishing time-preference (or declining concern for the present in comparison to the future). Democracy, which both in theory and evident historical fact accentuates time-preference to the point of convulsive feeding-frenzy, is thus as close to a precise negation of civilization as anything could be, short of instantaneous social collapse into murderous barbarism or zombie apocalypse (which it eventually leads to). As the democratic virus burns through society, painstakingly accumulated habits and attitudes of forward-thinking, prudential, human and industrial investment, are replaced by a sterile, orgiastic consumerism, financial incontinence, and a ‘reality television’ political circus. Tomorrow might belong to the other team, so it’s best to eat it all now.

The problem here is not that Land has drug this interpretation of the effect of democracy straight out of Plato’s Republic– which he has, or that it’s a kid who eats the marshmallow leads to zombie apocalypse reading of much more complex political relationships- which it is as well. Rather, it’s that there is no real evidence that it is true, and indeed the reason it’s not true might give those truly on the radical left who would like to abandon the US Constitution for something more modern and see nothing special in its antiquity reason for pause.

The study,of course, needs to be replicated, but a paper just out by Hal Hershfield, Min Bang and Elke Weber at New York University seems to suggest that the way to get a country to pay serious attention to long term investments is not to give them a deep future but a deep past and not just any past- the continuity of their current political system.

Our thinking is that the countries who have a longer past are better able see further forward into the future and think about extending the time period that they’ve already been around into the distant future. And that might make them care a bit more about how environmental outcomes are going to play out down the line.

And from further commentary on that segment:

Hershfield is not using the historical age of the country, but when it got started in its present form, when its current form of government got started. So he’s saying the U.S. got started in the year 1776. He’s saying China started in the year 1949.

Now, China, of course, though, is thousands of years old in historical terms, but Hershfield is using the political birth of the country as the starting point for his analysis. Now, this is potentially problematic, because for some countries like China, there’s a very big disparity in the historical age and when the current form of government got started. But Hershfield finds even when you eliminate those countries from the equation, there’s still a strong connection between the age of the country and its willingness to invest in environmental issues.

The very existence of strong environmental movements and regulation in democracies should be enough to disprove Land’s thesis about popular government’s “compulsive feeding frenzy”. Democracies should have stripped their environments bare like a dog with a Thanksgiving turkey bone. Instead the opposite has happened. Neo-reactionaries might respond with something about large hunting preserves supported by the kings, but the idea that kings were better stewards of the environment and human beings (I refuse to call them “capital”) because they own them as personal property can be countered with two words and a number King Leopold II.

Yet, we progressives need to be aware of the benefits of political continuity. The right with their Tea Party and their powdered wigs has seized American history. They are selling a revolutionary dismantling of the state and the deconstruction of hard fought for legacies in the name of returning to “purity”, but this history is ours as much as theirs even if our version of it tends to be as honest about the villains as the heroes. Neo-reactionaries are people who have woken up to the reality that the conservative return to “foundations” has no future. All that is left for them is to sit around daydreaming that the American Revolution and all it helped spark never happened, and that the kings still sat on their bedeckled thrones.