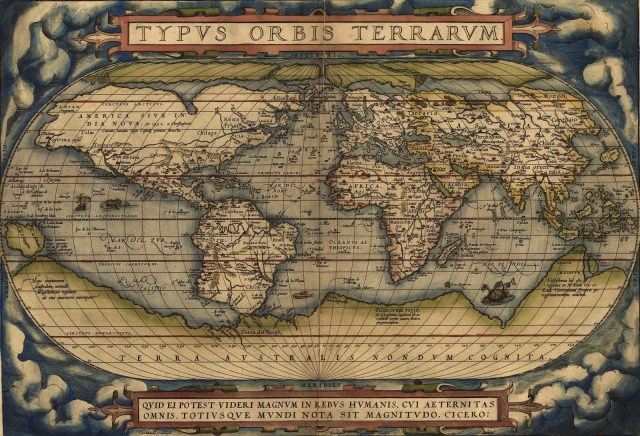

Between us and the future stands an almost impregnable wall that cannot be scaled. We cannot see over it,or under it, or through it, no matter how hard we try. Sometimes the best way to see the future is by is using the same tools we use in understanding the present which is also, at least partly, hidden from direct view by the dilemma inherent in our use of language. To understand anything we need language and symbols but neither are the thing we are actually trying to grasp. Even the brain itself, through the senses, is a form of funnel giving us a narrow stream of information that we conflate with the entire world.

We use often science to get us beyond the box of our heads, and even, to a limited extent, to see into the future. Less discussed is the fact that we also use good metaphors, fables, and stories to attack the the wall of the unknown obliquely. To get the rough outlines of something like the essence of reality while still not being able to see it as it truly is.

It shouldn’t surprise us that some of the most skilled writers at this sideways form of wall scaling ended up becoming blind. To be blind, especially to have become blind after a lifetime of being able to see, is to realize that there is a form to the world which is shrouded in darkness, that one can get to know only in bare outlines, and only with indirect methods. Touch in the blind goes from a way to know what something feels like for the sighted to an oblique and sometimes more revealing way to learn what something actually is.

The blind John Milton was a genius at using symbolism and metaphor to uncover a deeper and hidden reality, and he probably grasped more deeply than anyone before or after him that our age would be defined not by the chase after reality, but our symbolic representation of its “value”, especially in the form of our ever more virtual talisman of money. Another, and much more recent, writer skilled at such an approach, whose work was even stranger than Milton’s in its imagery, was Jorge Luis Borges whose writing defies easy categorization.

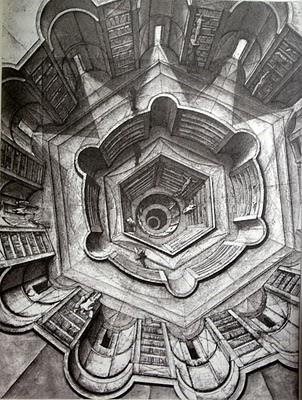

Like Milton did for our confusion of the sign with the signified in his Paradise Lost, Borges would do for the culmination of this symbolization in the “information age” with perhaps his most famous short-story- The Library at Babel. A story that begins with the strange line:

The universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite, perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries. (112)

The inhabitants of Borges’ imagined Library (and one needs to say inhabitants rather than occupants, for the Library is not just a structure but is the entire world, the universe in which all human-beings exist) “live” in smallish compartments attached to vestibules on hexagonal galleries lined with shelves of books. Mirrors are so placed that when one looks out of their individual hexagon they see a repeating pattern of them- the origin of arguments over whether or not the Library is infinite or just appears to be so.

All this would be little but an Escher drawing in the form of words were it not for other aspects that reflect Borges’ pure genius. The Library contains not just all books, but all possible books, and therein lies the dilemma of its inhabitants- for if all possible books exist it is impossible to find any particular book.

Some book explaining the origin of the Library and its system of organization logically must exist, but that book is essentially undiscoverable, surrounded by a perhaps infinite number of other books the vast number of which are just nonsensical combinations of letters. How could the inhabitants solve such a puzzle? A sect called the Purifiers thinks it has the answer- to destroy all the nonsensical books- but the futility of this project is soon recognized. Destruction barely puts a dent in the sheer number of nonsensical books in the Library.

The situation within the Library began with the hope that all knowledge, or at least the key to all knowledge, would be someday discovered but has led to despair as the narrator reflects:

I am perhaps misled by old age and fear but I suspect that the human species- the only species- teeters at the verge of extinction, yet that the Library- enlightened, solitary, infinite, perfectly unmoving, armed with precious volumes, pointless, incorruptible and secret will endure. (118)

The Library of Babel published in 1941 before the “information age” was even an idea seems to capture one of the paradoxes of our era. For the period in which we live is indeed experiencing an exponential rise of knowledge, of useful information, but this is not the whole of the story and does not fully reveal what is not just a wonder but a predicament.

The best exploration of this wonder and predicament is James Gleick’s recent brilliant history of the “information age” in his The Information: A History, A Theory, A Flood. In that book Gleick gives us a history of information from primitive times to the present, but the idea that everything: from our biology to our society to our physics can be understood as a form of information is a very recent one. Gleick himself uses Borges’ strange tale of the Library of Babel as metaphor through which we can better grasp our situation.

The imaginative leap into the information age dates from seven year after Borges’ story was published, in 1948, when Claude Shannon a researcher for Bell Labs published his essay “A Mathematical Theory of Communication”. Shannon was interested in how one could communicate messages over channels polluted with noise, but his seemingly narrow aim ended up being revolutionary for fields far beyond Shannon’s purview. The concept of information was about to take over biology – in the form of DNA, and would conquer communications in the form of the Internet and exponentially increasing powers of computation – to compress and represent things as bits.

The physicists John Wheeler would come to see the physical universe itself and its laws as a form of digital information- “It from bit”.

Otherwise put, every “it” — every particle, every field of force, even the space-time continuum itself — derives its function, its meaning, its very existence entirely — even if in some contexts indirectly — from the apparatus-elicited answers to yes-or-no questions, binary choices, bits. “It from bit” symbolizes the idea that every item of the physical world has at bottom — a very deep bottom, in most instances — an immaterial source and explanation; that which we call reality arises in the last analysis from the posing of yes-or-no questions and the registering of equipment-evoked responses; in short, that all things physical are information-theoretic in origin and that this is a participatory universe.

Gleick finds this understanding of reality as information to be both true in a deep sense and also in many ways troubling. We are it seems constantly told that we are producing more information on a yearly basis than all of human history combined, although what this actually means is another thing. For there is a wide and seemingly unbridgeable gap between information and what would pass for knowledge or meaning. Shannon himself acknowledged this gap, and deliberately ignored it, for the meaningfulness of the information transmitted was, he thought, “irrelevant to the engineering problem” involved in transmitting it.

The Internet operates in this way, which is why a digital maven like Nicholas Negroponte is critical of the tech-culture’s shibboleth of “net neutrality”. To humorize his example, a digital copy of a regular sized novel like Fahrenheit 451 is the digital equivalent of one second of video from What does the Fox Say?, which, however much it cracks me up, just doesn’t seem right. The information content of something says almost nothing about its meaningfulness, and this is a problem for anyone looking at claims that we are producing incredible amounts of “knowledge” compared to any age in the past.

The problem is perhaps even worse than at first blush. Take these two sets of numbers:

9 2 9 5 5 3 4 7 7 10

And:

9 7 4 3 8 5 4 2 6 3

The first set of numbers is a truly random set of the numbers 1 through 10 created using a random number generator. The second set has a pattern. Can you see it?

In the second set every other number is a prime number between 2 and 7. Knowing this rule vastly decreases the possible set of 10 numbers between 1 and 10 which a set of numbers can fit. But here’s the important takeaway- the the first set of numbers contains vastly more information than the second set. Randomness increases the information content of a message. (If anyone out there has a better grasp of information theory thinks this example is somehow misleading or incorrect please advise.)

The new tools of the age have meant that a flood of bits now inundates us the majority of which is without deep meaning or value or even any meaning at all.We are confronted with a burst dam of information pouring itself over us. Gleick captures our dilemma with a quote from the philosopher of “enlightened doomsaying” Jean-Pierre Dupuy:

I take “hell” in its theological sense i.e. a place which is devoid of grace – the underserved, unnecessary, surprising, unforeseen. A paradox is at work here, ours is a world about which we pretend to have more and more information but which seems to us increasingly devoid of meaning. (418)

It is not that useful and meaningful information is not increasing, but that our exponential increase in information of value- of medical and genetic information and the like has risen in tandem with an exponential increase in nonsense and noise. This is the flood of Gleick’s title and the way to avoid drowning in it is to learn how to swim or get oneself a boat.

A key to not drowning is to know when to hold your breath. Pushing for more and more data collection might sometimes be a waste of resources and time because it is leading one away from actionable knowledge. If you think the flood of useless information hitting you that you feel compelled to process is overwhelming now, just wait for the full flowering of the “Internet of Things” when everything you own from your refrigerator to your bathroom mirror will be “talking” to you.

Don’t get me wrong, there are aspects that are absolutely great about the Internet of Things. Take, for example, the work of the company Indoo.rs that has created a sort of digital map throughout the San Francisco International Airport that allows a blind person using bluetooth to know: “the location of every gate, newsstand, wine bar and iPhone charging station throughout the 640,000-square-foot terminal.”

This is exactly the kind of purpose the Internet of Things should be used for. A modern form of miracle that would have brought a different form sight to those blind like Milton and Borges. We could also take a cue from the powers of imagination found in these authors and use such technologies to make our experience of the world deeper our experience more multifaceted, immersive. Something like that is a far cry from an “augmented reality” covered in advertisements, or work like that of neuroscientist David Eagleman, (whose projects I otherwise like), on a haptic belt that would massage its wearer into knowing instantaneously the contents of the latest Twitter feed or stock market gyrations.

Our digital technology where it fails to make our lives richer should be helping us automate, meaning to make automatic and without thought, all that is least meaningful in our lives – this is what machines are good at. In areas of life that are fundamentally empty we should be decreasing not increasing our cognitive load. The drive for connectivity seems pushing in the opposite direction, forcing us to think about things that were formerly done by our thoughtless machines over which we lacked precision but also didn’t give us much to think about.

Yet even before the Internet of Things has fully bloomed we already have problems. As Gleick notes, in all past ages it was a given that most of our knowledge would be lost. Hence the logic of a wonderful social institution like the New York Public Library. Gleick writes with sharp irony:

Now expectations have inverted. Everything may be recorded and preserved…. Where does it end? Not with the Library of Congress.

Perhaps our answer is something like the Internet Archive whose work on capturing recording all of the internet as it comes into being and disappears is both amazing and might someday prove essential to the survival of our civilization- the analog to copies having been made of the famed collection at the lost Library at Alexandria. (Watch this film).

As individuals, however, we are still faced with the monumental task of separating the wheat from the chaff in the flood of information, the gems from the twerks. Our answer to this has been services which allow the aggregation and organization of this information, where as Gleick writes:

Searching and filtering are all that stand between this world and the Library of Babel. (410)

And here is the one problem I had with Gleick’s otherwise mind blowing book because he doesn’t really deal with questions of power. A good deal of power in our information society is shifting to those who provide these kinds of aggregating and sifting capabilities and claim on that basis to be able to make sense of a world brimming with noise and nonsense. The NSA makes this claim and is precisely the kind of intelligence agency one would predict to emerge in an information age.

Anne Neuberger, the Special Assistant to NSA Director Michael Rogers and the Director of the NSA’s Commercial Solutions Center recently gave a talk at the Long Now Foundation. It was a hostile audience of Silicon Valley types who felt burned by the NSA’s undermining of digital encryption, the reputation of American tech companies, and civil liberties. But nothing captured the essence of our situation better than a question from Paul Saffo.

Paul Saffo: It seems like the intelligence community have always been data optimists. That if we just had more data, and we know that after every crisis, it’s ‘well if we’d just have had more data we’d connect the dots.’ And there’s a classic example, I think of 9-11 but this was said by the Church Committee in 1975. It’s become common to translate criticism of intelligence results into demands for enlarged data collection. Does more data really lead to more insight?

As a friend is fond of saying ‘perhaps the data haystack that the intelligence community has created has become too big to ever find the needle in.’

Neuberger’s telling answer was that the NSA needed better analytics, something that the agency could learn from the big data practices of business. Gleick might have compared her answer to a the plea for a demon by a character in a story by Stanislaw Lem whom he quotes.

We want the Demon, you see, to extract from the dance of atoms only information that is genuine like mathematical formulas, and fashion magazines. (The Information 425)

Perhaps the best possible future for the NSA’s internet hoovering facility at Bluffdale would be for it to someday end up as a memory bank of the our telecommunications in the 21st century, a more expansive version of the Internet Archive. What it is not, however,is a way to anticipate the future on either small or large scales, or at least that is what history tells us. More information or data does not equal more knowledge.

We are forced to find meaning in the current of the flood. It is a matter of learning what it is important to pay attention to and what to ignore, what we should remember and what we can safely forget, what the models we use to structure this information can tell us and what they can’t, what we actually know along with the boundaries of that which we don’t. It is not an easy job, or as Gleick says:

Selecting the genuine takes work; then forgetting takes even more work.

And it’s a job, it seems, that just gets harder as our communications systems become ever more burdened by deliberate abuse ( 69.6 percent of email in 2014 was spam up almost 25 percent from a decade earlier) and in an age when quite extraordinary advances in artificial intelligence are being used not to solve our myriad problems, but to construct an insidious architecture of government and corporate stalking via our personal “data trails”, which some confuse with our “self”. A Laplacian ambition that Dag Kittlaus unguardedly praises as “Incremental revenue nirvana.” Pity the Buddha.

As individuals, institutions and societies we need to find ways stay afloat and navigate through the flood of information and its abuse that has burst upon us, for as in Borges’ Library there is no final escape from the world it represents. As Gleick powerfully concludes The Information:

We are all patrons of the Library of Babel now and we are the librarians too.

The Library will endure, it is the universe. As for us, everything has not been written; we are not turning into phantoms. We walk the corridors looking for lines of meaning amid the leagues of cacophony and incoherence, reading the history of the past and of the future, collecting our thought and collecting the thoughts of others, and every so often glimpsing mirrors in which we may recognize creatures of the information.”