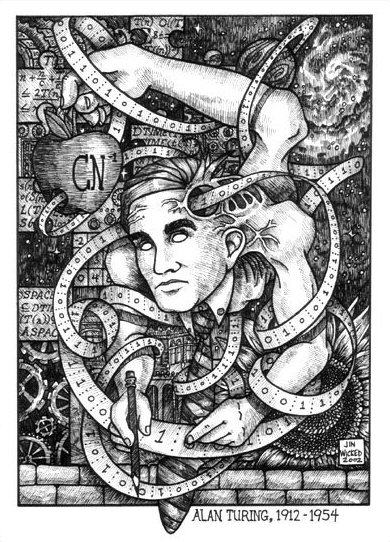

I propose to consider the question, “Can machines think?”

Thus began Alan Turing’s 1950 essay Computing Machinery and Intelligence without doubt the most import single piece written on the subject of what became known as “artificial intelligence”.

Straight away Turing insists that we won’t be able to answer this question by merely reflecting upon it. If we went about it this way we’d get all caught up in arguments over what exactly “thinking” means. Instead he proposes a test.

Turing imagines an imitation game composed of 3 players: (A) a man, (B) a woman, and (C) an interrogator with the role of the latter being to ask questions of the 2 players and determine which one is a man. Turing then transforms this game by exchanging the man with a machine, and replacing the woman with the man. The interrogator is then asked to figure out which is the real man:

We now ask the question, “What will happen when a machine takes the part of A in this game?” Will the interrogator decide wrongly as often when the game is played like this as he does when the game is played between a man and a woman? These questions replace our original, “Can machines think?”

The machine in question Turing now narrowly defines as a digital computer, which consists of 3 parts (i) Store, that is the memory, (ii) Executive Unit, that is the part of the machine that performs the operations, (iii) The Control, the part of the machine that makes sure the Executive Unit performs operations based upon instructions that make up part of the Store. Digital computers are also “discrete state” machines, that is they are characterized by clear on-off states.

This is all a little technical so maybe a non-computer example will help. We can perhaps best understand digital technology by comparing it to its old rival analog. Think about a selection of music stored on your iPod versus, say, your collection of vintage ‘70s

8 tracks. Your iPod has music stored in a discrete state- represented by 1s and 0s. It has an Executive Unit that allows you to translate these 1s and 0s into sound, and a Control that keeps the whole thing running smoothly and allows you, for example, to jump between tracks. Your 8 tracks, on the other hand, store music as “impressions” on a magnetic tape, not as discrete state representations, the “head”, in contact with the tape reverses this process and transforms the impressions back into sound, you move between the tracks by causing the head to actually physically move.

Perhaps Turing’s choice of digital over analog computers can be said to amount to a bet about how the future of computer technology would play out. By compressing information into 1s and 0s – as representation- you could achieve seemingly limitless Storage/Control capacity. Imagine if all the songs on your iPod needed to be stored on 8 tracks! If you wanted to build an intelligent machine using analog you might as well just duplicate the very biological/analog intelligence you were trying to mimic. Digital technology represented, for Turing, a viable alternative path to intelligence other than the biological one we had always known.

Back to his article. He rephrases the initial question:

Let us fix our attention on one particular digital computer C. Is it true that by modifying this computer to have an adequate storage, suitably increasing its speed of action, and providing it with an appropriate programme, C can be made to play satisfactorily the part of A in the imitation game, the part of B being taken by a man?

If we were able to answer this question in the affirmative, Turing insisted, then such a machine could be said to possess human level intelligence.

Turing then runs through and dismisses what he considers the most likely objections to the idea of whether or not a machine that could think could be built:

The Theological Objection– computers wouldn’t have a soul. Turing’ reply: Wouldn’t God grant a soul to any other being that possessed human level intelligence? What was the difference between bringing such an intelligent vessel for a soul into the world by procreation and by construction?

Heads in the Sand Objection– The idea that computers could be as smart as human is too horrible to be true. Turing’s reply: Ideas aren’t true or false based on our wishing them so.

The Mathematical Objection- Machines can’t understand logically consistent sentences such as “this sentence is false”. Turing’s reply: Okay, but, at the end of the day humans probably can’t either.

The Argument from Consciousness- Turing quotes a professor Lister: “”Not until a machine can write a sonnet or compose a concerto because of thoughts and emotions felt, and not by the chance fall of symbols, could we agree that machine equals brain-that is, not only write it but know that it had written it.” Turing’s reply: If this is to be the case, why don’t we apply the same prejudice to people. How do I really know that another human being thinks except through his actions and words?

The Argument from Disability- Whatever a machine does it will never be able to do X. Turing’s reply: These arguments are essentially making unprovable claims based on induction- that I’ve never seen a machine do X therefore no machine will ever do X.

Many of them are also alternative arguments from consciousness:

The claim that a machine cannot be the subject of its own thought can of course only be answered if it can be shown that the machine has some thought with some subject matter. Nevertheless, “the subject matter of a machine’s operations” does seem to mean something, at least to the people who deal with it. If, for instance, the machine was trying to find a solution of the equation x2 – 40x – 11 = 0 one would be tempted to describe this equation as part of the machine’s subject matter at that moment. In this sort of sense a machine undoubtedly can be its own subject matter.

Lady Lovelace’s Objection- Lady Lovelace, friend of Charles Babbage whose plans for his Analytical Engine in the early 1800s were probably the first fully conceived modern computer, and Lovelace perhaps the author of the first computer program had this to say:

“The Analytical Engine has no pretensions to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform”

Turing’s response: this is yet another argument from consciousness. The computers he works with surprise him all the time with results he did not expect.

Argument from the Continuity of the Nervous System: The nervous system is fundamentally different from a discrete state machine therefore the output of the two will always be fundamentally different. Turing’s response: The human brain is analogous to a “differential analyzer” (our old analog computer discussed above), and solutions of the two types of computers are indistinguishable. Hence a digital computer is able to do at least some things the analog computer of the human brain does.

Argument from the Informality of Behavior: Human beings, unlike machines, are free to break rules and are thus unpredictable in a way machines are not. Turing’s response: We cannot really make the claim that we are not determined just because we are able to violate human conventions. The output of computers can be as unpredictable as human behavior and this emerges despite the fact that they are clearly designed to follow laws i.e. are programmed.

Argument from ESP: Given a situation in which the man playing against the machine possesses some yet understood telepathic power he could always influence the interrogator against the machine and in his favor. Turing’s response: This would mean the game was rigged until we found out how to build a computer that could somehow balance out clairvoyance. For now, put the interrogator in a “telepathy proof room”.

So that, in a nutshell, is the argument behind the Turing test. By far, the most well known challenge to this test was made by the philosopher, John Searle, (relation to the author has been lost in the mist of time). Searle has so influenced the debate around the Turing test that it might be said that much of the philosophy of mind that has dealt with the question of artificial intelligence has been a series of arguments about why Searle is wrong.

Like Turing, Searle in his 1980 essay, Minds Brains and Programs, will introduce us to a thought experiment:

Suppose that I’m locked in a room and given a large batch of Chinese writing. Suppose furthermore (as is indeed the case) that I know no Chinese, either written or spoken, and that I’m not even confident that I could recognize Chinese writing as Chinese writing distinct from, say, Japanese writing or meaningless squiggles. To me, Chinese writing is just so many meaningless squiggles.

Now suppose further that after this first batch of Chinese writing I am given a second batch of Chinese script together with a set of rules for correlating the second batch with the first batch. The rules are in English, and I understand these rules as well as any other native speaker of English. They enable me to correlate one set of formal symbols with another set of formal symbols, and all that ‘formal’ means here is that I can identify the symbols entirely by their shapes. Now suppose also that I am given a third batch of Chinese symbols together with some instructions, again in English, that enable me to correlate elements of this third batch with the first two batches, and these rules instruct me how to give back certain Chinese symbols with certain sorts of shapes in response to certain sorts of shapes given me in the third batch.

With some additions, this is the essence of Searle’s thought experiment, and what he wants us to ask: does the person in this room moving around a bunch of symbols according to a set of predefined rules actually understand Chinese? And our common sense answer is- “of course not!”

Searle’s argument is actually even more clever than it seems because it could having been taken right from one of Turing’s own computer projects. Turing had written a computer program that could have allowed a computer to play chess. I say could have allowed because there wasn’t actually a computer at the time sophisticated enough to run his program. What Turing did then was to use the program as a set of rules he used to play a human being in chess. He found that by following the rules he was unable to beat his friend in chess. He was, however, able to beat his friend’s wife! (No sexism intended).

Now had Turing given these rules to someone who knew nothing about chess at all they would have been able to play a reasonable game. That is, they would have played a reasonable game without having any knowledge or understanding of what it was they were actually doing.

Searle’s goal is to bring into doubt what he calls “strong AI” the idea that the formal manipulation of symbols- syntax- can give rise to the true understanding of meaning- semantics. He identifies part of our problem in our tendency to anthropomorphize our machines:

The reason we make these attributions is quite interesting, and it has to do with the fact that in artifacts we extend our own intentionality; our tools are extensions of our purposes, and so we find it natural to make metaphorical attributions of intentionality to them; but I take it no philosophical ice is cut by such examples. The sense in which an automatic door “understands instructions” from its photoelectric cell is not at all the sense in which I understand English.

Even with this cleverness, Searle’s argument has been shown to have all sorts of inconsistencies. Among the best refutations I’ve read is one of the early ones- Margaret A. Boden’s 1987 essay Escaping the Chinese Room. In gross simplification Boden’s argument is this: Look, normal human consciousness is made up of a patchwork of “stupid” subsystems that don’t understand or possess what Searle claims is the foundation stone of true thinking- intentionality- “subjective states that relate me to the rest of the world”- in anything like his sense at all. In fact, most of what the mind does is made up of these “stupid” processes. Boden wants to remind us that we really have no idea how these seemingly dumb processes somehow add up to what we experience as human level intelligence.

Still, what Searle has done has made us aware of the huge difference between formal symbol manipulation and what we would call thinking. He made us aware of the algorithms (a process or set of rules to be followed in calculations or other problem-solving operations) that would become a simultaneous curse and backdrop of our own day. A day when our world has become mediated by algorithms in its economics, its warfare, in our choice of movies and books and music, in our memory and cognition (Google) in love (dating sites) and now it seems in its art (see the excellent presentation by Kevin Slavin How Algorithms Shape Our World). Algorithms that Searle ultimately understood to be lifeless.

In the words of the philosopher Andrew Gibson on Iamus’ Hello World!:

I don’t really care that this piece of art is by a machine, but the process behind it is what is problematic. Algorithmization is arguably part of this ultra-modern abstractionism, abstracting even the artist.

The question I think that should be asked here is how exactly Iamus, the algorithm that composed, Hello World! worked? The composition Hello World! was created using a very particular form of algorithm known as a genetic algorithm, or, in other words Iamus is a genetic algorithm. In very over-simplified terms a genetic algorithm works like evolution. There is (a) a “population” of randomly created individuals (in Iamus’ case it would be sounds from a collection of instruments). Those individuals are the selected against (b) an environment for the condition of best fit (I do not know in Iamus’ case if this best fit was the judgement of classically trained humans, some selection of previous human created compositions, or something else), the individual that survive (are chosen to best meet the environment) are then combined to form new individuals (compositions in Iamus’ case) (c) an element of random features is introduced to individuals along the way to see if they help individuals better meet the fit. The survivor that best meets the fit is your end result.

Searle would obviously claim that Iamus was just another species of symbol manipulation and therefore did not really represent something new under the sun, and in a broad sense I fully agree. Nevertheless, I am not so sure this is the end of the story because to follow Searle’s understanding of artificial intelligence seems to close as many doors as it opens in essence locking Turing’s machine, forever, into his Chinese room. Searle writes:

I will argue that in the literal sense the programmed computer understands what the car and the adding machine understand, namely, exactly nothing. The computer understanding is not just (like my understanding of German) partial or incomplete; it is zero.

For me, the line he draws between intelligent behavior or properties emerging from machines and those emerging from biological life is far too sharp and based on rather philosophically slippery concepts such as understanding, intentionality, causal dependence.

Whatever else intentionality is, it is a biological phenomenon, and it is as likely to be as causally dependent on the specific biochemistry of its origins as lactation, photosynthesis, or any other biological phenomena.

Taking Turing’s test and Searle’s Chinese Room together leaves us, I think, lost in a sort of intellectual trap. On the one side we having Turing arguing that human thinking and digital computation are essentially equivalent. All experience points to the fact that this is false. On the other side we have Searle arguing that digital computation and the types of thinking done by biological creatures are essentially nothing alike. An assertion that is not obviously true. The problem here is that we lose what are really the two most fundamental questions and that is how are computation and thought alike, and how are they different?

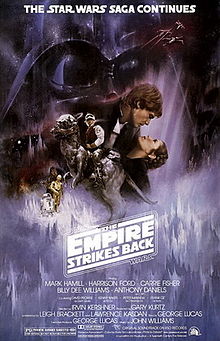

Instead what we have is something like Iamus “introduced” to the world, along with its creation as if it were a type of person, by the Turing faction when in fact it has almost none of these qualities that we consider to be constitutive of personhood. A type of showmanship that put me in mind of the wanderings of the Mechanical Turk. The 18th century mechanical illusion that for a time fooled the courts of Europe into thinking a machine could defeat human beings at chess. (There was, of course, a short person inside.)

To this, the Searle faction responds with horror and utter disbelief aiming to disprove that such a “soulless” thing as a computer could ever, in the words of Turing’s Lister: “write a sonnet or compose a concerto”, that was not a product of nothing other than” the chance fall of symbols”. The problem with this is that our modern day Mechanical Turks are no longer mere illusions- there is no longer a person hiding inside- and our machines really do defeat grand masters in chess, and win trivia games, and write news articles, and now compose classical music. Who knows where this will stop, if it indeed if it will stop, and how many what have long been considered the most human defining activities qualities will be successfully replicated, and even surpassed, by such machines.

We need to break through this dichotomy and start asking ourselves some very serious questions. For only by doing so are we likely to arrive at an understanding both of where we are as a technology dependent species and where what we are doing is taking us. Only then will we have the means to make intentional choices about where we want to go.

I will leave off here with something shared with me by Andrew Gibson. It is a piece by his friend Amanda Feery composed in memory of Turing’s centenary entitled “Turing’s Epitath”.

And I will leave you with questions:

How is this similar to Iamus’ Hello World!? And how is it different?