That’s the light stuff, I will spare you the horror show.

Disease was an ever present danger as well. The Plague is only the most infamous of the diseases in the early 1500s that prematurely killed countless numbers of people, which included; influenza, dysentery, cholera, small pox, and a mysterious disease with the innocuous name of “

English Sweat” that started with the chills and killed a person within a day.

Many of these diseases found their vector in the almost non-existent sanitary conditions of the time. Many simply threw their waste, including human waste, out onto the street.

As a further indicator of the general lack of sanitation and personal hygiene,Thomas More’s great friend, Erasmus, wrote one of the first books on manners that commended people urinating in public to face a wall rather than piss into public sight, refrain from licking their food dishes, or wiping their snotty noses onto tablecloths.

The 1500s and 1600s would witness cultural pandemics as well. Witch mania in which would leave up to 80,000 women in Europe dead, a large number by burning. If this was on the one hand a reflection of how horribly off course European religious ideas were moving, it is also gives us a glimpse into just how vulnerable lower-class women, lacking the protections of being the “property” of well-born males, were to the madness of clergy and crowd.

Witch burning, and public executions would pale, however, before the surge of violence of the European Wars of Religion which were just stirring as Thomas More penned his Utopia, the bloody conflict between the Catholic Church and the new Protestant groups that were sprouting up all over Europe. We would not see casualty rates like this again until the Second World War with perhaps over 5 million killed. The culmination of the conflict between Catholics and Protestants in England with the English Civil War (1642-1651) would kill a larger proportion of British citizens than World War I. (Pinker BA 142). These wars had a nationalistic or “nation-building” aspect as well, the prelude to the English Civil War was The Bishop’s War (1639-1640) a conflict that forcefully wed Scotland to England.

Thomas More himself would be caught up in the fanaticism of the European Religious Wars in many way abandoning the Christian-humanism that had informed his Utopia, for what some might call an extremist defense of Catholicism. For this, he paid with his life after having resisted the move by Henry VIII to declare himself head of the Church in England. More was fortunately not killed in the typical way persons accused of treason were treated ,which would have been to be hung till near death, his body taken down and fastened to horses, to be pulled at until he was ripped into pieces. Rather, the executioner merely cut off his head.

If we had a time machine and brought Thomas More to England in the year 2012- almost 500 years after he wrote Utopia what would he see?

The life expectancy for an English male is now a little more than double what it was in 1516- 78 years (for women it is 82). A disturbing number, 36, infants are killed by their parents in England each year around, but we have every reason to suspect that this is not even near the number of infanticides per day in 1516. The last peacetime famine in England proper was 1634. The last devastating pandemic was in 1918. The last act of capital punishment was in 1969. The last “witch” executed in 1684.

“Today, according to British standards, the minimum provision of sanitary appliances for a private dwelling is: “One toilet for up to four people, two toilets for five people or more, a washbasin in or adjacent to every toilet, one bath or shower for up to four

people, one kitchen sink.”

The distinction in English attitudes to religion between the days of Thomas More and today can be seen in a great blog by a young ex-fundamentalist Christian, Jonny Scaramanga, called Leaving Fundamentalism which points out many of the absurdities of fundamentalism. In 1516, Jonny wouldn’t have lasted a day.

Of course, within the lifetime of people still living we did have The Second World War, which proportionally killed as many Europeans as the Wars of Religion, but we have seen nothing like it since. The very idea that Great Britain would fight another such conflict, especially against other European powers, within our lifetime, those of our children, or even the generation after them, seems, in a way it never has been before, ludicrous. Indeed, even in terms of nationalism we certainly live in a different age. Scotland looks likely to soon hold a referendum on independence from Great Britain, and absolutely no one thinks a verdict in favor of the Scotts going their own way will lead to civil war.

In other words, our time traveling Thomas More, were he to set foot in the England of today, would very likely think he had stepped into Utopia.

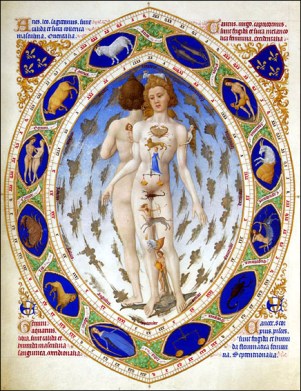

The side of this argument that takes note of the remarkable decline of violence in the modern era from the near end of judicial torture, of religious persecution, of slavery, of infanticide, of wife and children beating, of the use of the coercive power of the state to enforce moral norms (homosexuality, adultery), of the gratuitous abuse of animals, of genocide and politicide practiced by the big advanced powers, and the seeming disappearance of the willingness of those powers to go to war with one another is something meticulously laid out by Steven Pinker in his The Better Angels of Our Nature. In part Pinker credits, or characterizes, this decline of violence to an expansion of human beings’ “circle of empathy”, an idea he borrows from the philosopher Peter Singer. Over time we have come to extend the kind of compassion human beings are naturally geared for, largely towards members of of own family or tribe, to other human beings, and even other animals.

Elsewhere I will offer an alternative reading of Pinker’s argument that sees these developments much less brightly than he does. For now, I will merely accept them as fact and turn my attention to Pinker’s attitude towards what I have called elsewhere “the utopian tradition”. For Pinker sees in utopia a major source of past violence, and as a consequence misses the very real and positive role the utopian imagination played in getting us to the conditions of today he so praises.

In setting out to identify both the reason the first half of the 20th century was so violent, and why, the world since has been so much less so, Pinker identifies a culprit in the rise and fall in the idea of utopia.

Why does the idea of utopia lead to violence?

“In utopia, everyone is happy forever, so its moral value is infinite”. The scale of such a promise leads to an abandonment of any limit on the price to be paid for utopia , especially in terms of the lives of others. Pinker: “How many people would it be permissible to sacrifice to attain that infinite good? A few million can seem like a pretty good bargain.” (BA 328)

Another way in which Pinker thinks utopia inspires violence because those who oppose such an infinite good can only be motivated by its opposite- absolute evil. Pinker: “They are the only things standing in the way of a plan that could lead to infinite goodness. You do the math.”

In the mind of Pinker, utopian ideas also lead to genocide because they need to force people into a strictly laid plan:

“In utopia, everything is there for a reason. What about the people? Well groups of people are diverse. Some of them stubbornly, perhaps essentially, cling to values that are out of place in a perfect world…. “If you are designing a perfect society on a clean sheet of paper, why not write these eyesores out of the plan from the start”. (BA 329)

Pinker loves citations, and seemingly every paragraph in his 802 page Better Angels has at least one. Except, that is, for these paragraphs, so I am not sure where Pinker is getting his version of the utopian mindset he finds so dangerous. Instead he turns to the a work by Ben Kiernan, Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Seemingly on the basis of that work, Pinker claims of utopian ideologies: “Time and again, they hark back to a vanished agrarian paradise, which they seek to restore to a healthful substitute for the prevailing urban decadence”. He contrasts these utopian purists to the “intellectual bazaar of cosmopolitan cities” from which grew the implicitly non-utopian, healthy and rational ideas of the Enlightenment. (BA 329).

This theory of the agrarian-utopians vs the cosmopolitan-rationalists seems to make a lot of sense, nevertheless it is wrong. If any revolution was the Enlightenment’s revolution it was the American, and many of America’s Enlightenment heavy weights spoke against the “vices” of the city and the “virtue” of the countryside. Jefferson is best known for this, but an Enlightenment thinker Pinker appears to admire even more- James Madison- was an agro-phile as well. Here’s Madison:

“Tis not the country that peoples either the Bridewells or the Bedlams. These mansions of wretchedness are tenanted from the distresses and vices of overgrown cities” (If Men were Angels p. 90).

Pinker is certainly right in asserting that a certain group of utopian ideologies: French Revolutionaries, Soviet Communists, Maoists in China and elsewhere, and Islamic Jihadists are a group with an incalculable amount of blood on their hands. He uses a quote from the most blood-soaked of the French Revolutionaries as evidence that the crimes of utopians arise from their denial of human nature.

Robespierre: “The French people seem to have outstripped the rest of humanity by two thousand years; one might be tempted to regard them, living amongst them, as a different species”. (BA 186)

Yet, what is revealing to me about this quote is not its supposed denial of human nature as its clear indication that underneath Robespierre’s utopian ideology lay an idea of universal history. That is, he thought himself and his fellow revolutionaries were the people of the future, that this was ultimately where history was taking the human race, the French had just gotten there first.

And, when you look at it that way you see that all of Pinker’s bloodsoaked utopian ideologies were determinist theories of history in one way or another French Revolutionaries, yes, but also Nazis with their theory of history as a Darwinian struggle, and Soviet Communists, and Maoists with their ideas of history as a class war, and Jihadists along with Christian millennialist both of whom see history moving us towards a divine showdown.

But wait a second, isn’t Pinker’s own theory a determinist theory of history? Not if one takes his hedging at face value, but Kant’s theory which serves as a foundation of Pinker’s ideas certainly was one. Yet, neither Kant’s nor Pinker’s theories really build a positive role for violence in the movement of history. Certainly this must be the main thing: ideas that give rise to extreme violence tend to be theories of history that look at violence as somehow deeply embedded in the unfolding of history. Though, even here we need to be historically careful, for the American Civil War which resulted in abolition was itself infused with a millenarian based violence, so there is more to the story than meets the eye.

Pinker’s belief that utopian ideas are primarily a source of ideologically based violence blinds him to the way in which the idea of utopia helped move his humanitarian revolutions along. The list below is not meant to be comprehensive, and though each of these works or communities have deep flaws, when viewed from a modern perspective they no doubt helped moves things step-by-step forward to the place we are today:

Plato, The Republic: Often today viewed as a source of totalitarianism (more on that in a minute) A large part of The Republic is devoted to limiting the horrors of war- including the horrors of genocide, rape, and enslavement. The book also made the case for the political equality of women.

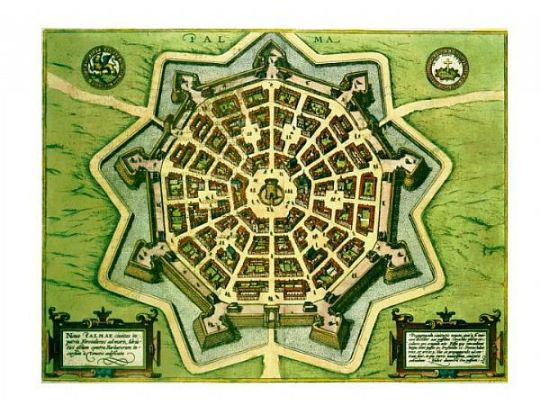

Thomas More, Utopia (1516): Religious tolerance: rather than heretics being killed even atheists are tolerated and encouraged to talk out their ideas. Violence: In More’s Utopia slavery is legal, but one should remember how why these slaves exists- that Utopia tries to avoid killing its enemies in war, and no longer executes common criminals. More’s use of his Utopia to criticize the inhumanity of the Enclosure movement was discussed above.

Francis Bacon, New Atlantis (1627): Imagined a society in which the general welfare of all would be raised by the application of the nascent scientific method.

Gabriel Plattes, A Description of the Famous Kingdom of Marciana (1641): Public health: “for they have an house or College of Experience where they deliver out yearly such medicines as they find out by experience and all such as shall be able to demonstrate any experiment for the health or wealth of men are honourably rewarded at the publick charge by which their skill in husbandy physick and surgery is most excellent”.

Margaret Cavendish, A Blazing World (1666): Womens’ rights, animal rights, and perhaps the first person to argue against the use of animals in scientific testing.

The Commowealth of Pennsylvania (1681): Religious Tolerance: In the 1700s no American colony so captured the European longing for utopia and paradise than my home state of Pennsylvania of which Voltaire said: ” So, William Penn might be said to have brought back the Golden Age which never existed save in Pennsylvania.”

Mary Astell, A Serious Proposal to the Ladies (1694): Women’s rights, famous for her quote: “If all men are born free, how is it that all women are born slaves?”

David Hume, Idea of a Perfect Commonwealth (1742): The classical liberal’s utopian: separation of powers, extension of the franchise to all of the propertied, decentralization, separation of church and state.

Sarah Scott, A Description of Millenium Hall and the Country Adjacent (1762): Women’s rights, universal education, and liberal economic equality.

Immanuel Kant, On Perpetual Peace (1802): Another classical liberal’s utopian: How the expansion of representative democracy, trade, and international law might result in the disappearance of war from human history.

Anonymous: Equality: a history of Lithconia (1802): Retirement, old age pensions.

Robert Owen’s Community at New Harmony (1824): In the midst of the horrendous working conditions of the early industrial revolution, Owen established experimental communities that tried to improve the general conditions of workers.

Northampton Association’s Abolitionist Utopia (1842): In 1842, a group of radical abolitionists and social reformers established the Northampton Association of Education and Industry, a utopian community in western Massachusetts organized around a collectively owned and operated silk mill. Members sought to challenge the prevailing social attitudes of their day by creating a society in which “the rights of all are equal without distinction of sex, color or condition, sect or religion.”

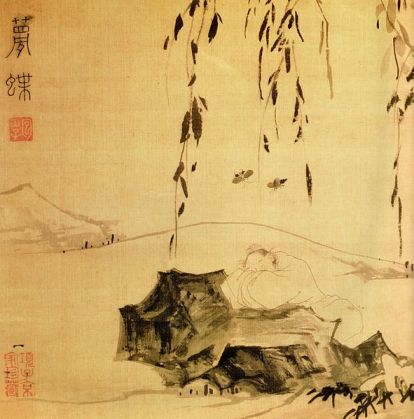

John Stuart Mill, Principles of Political Economy 3rd Edition (1852): Usually considered among the classical liberals, Mill postulates here an end to the logic of endless economic growth instead giving way to concentration of human beings moral and intellectual growth.

Jean-Baptiste Andre-Godin’s Phalanstery for Workers Families (1871): Another utopian experiment in ways to alleviate the miserable conditions of industrial workers.

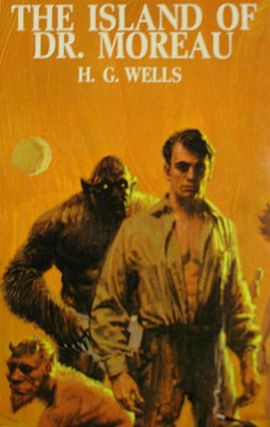

H.G. Wells, A Modern Utopia (1905): Equal rights for women. Animal rights.

Aldous Huxley, Island (1962): Sexual liberation. Decriminalization of drug use.

The Civil Rights Movement 1960s: The Civil Rights Movement grew directly out three utopian claims. The first an Enlightenment claim of human equality, the second a Christian-millennialist claim of an age of universal brotherhood “I have a dream”,

and lastly the utopian aspirations of non-violence found in Ghandi.

1960’s Communes, Anti-War, and the birth of the Internet: The commune movement of the 1960s may seem in retrospect silly, and much of it was, but it did have some positive effects: it was part of the larger anti-war movement that put a premium on non-violence “all you need is love”, and many of its members went on to create what they thought would be the next liberating technology- the Internet.

Ernest Callenbach, Ecotopia: The Notebooks and Reports of William Weston (1975): Biodiversity: An increased status for natural animals, plants, and ecosystems.

So, if the utopian tradition played such an obvious role in the expansion of Pinker’s (and Singer’s) circle of empathy, indeed, if it played such an obvious role in the other utopian trends seen in modern life, how does Pinker miss it? My guess, is that his views have been biased by the work of two influential authors on the subject of utopia, the historian, Karl Popper, and Pinker himself.

Karl Popper was just the most prominent of scholars after the Second World War who in trying to understand what went wrong laid their finger on utopia. In his, Open Society and Its Enemies, Popper especially indicted Plato, Hegel, and Marx as three figures who had lead the world down a dangerous path to believing that utopian projects could be brought into reality, and that this had resulted in the great bloodshed of the 20th century.

Popper was reasonably reacting against what is called “The Authoritarian High Tide of Modernism”, which included among other things the belief by intellectuals that society could be re-engineered in whatever way they deemed. Popper wanted policy makers to adopt instead the viewpoint of “piecemeal social engineering” rather than think society’s problems might be fixed all at one go. Nothing wrong with that. The problem is more one of association. By bringing Plato, who had merely imagined an alternative society to his own, and by reading him out of his historical context with the eyes of a modern liberal whose society had morally and intellectually evolved by leaps and bounds over the world in the times of Plato- Popper seemed to indict the utopian tradition in its entirety.

Popper’s association of the attempt to redesign society whole cloth with inevitable violence is blind to the reality of what almost all real world utopias were- small scale experiments that grew out of the political, economic, and social problems of their day that while they almost universally would ultimately fail- killed no one, insofar as one makes exceptions for those few cases where the “utopia” in question was in reality a religious or New Age cult.

Just how far this downgrading of utopia has gone is reflected in the conservative writer, Mark Levin’s recent best selling book, Ameritopia, where Levin uses Popper’s mis-association of utopia with mass murder, to indict accomplishments in Western societies that utopian movements were often in the forefront of, such as old age pensions (Social Security), and government funded health care.

Still, if Popper was one of the influences that lead Pinker to his misreading of utopia there is also the influence of Pinker upon himself. Better Angels of Our Nature should be read in conjunction with his earlier book The Blank Slate to best understand where Pinker is coming from.

In The Blank Slate Pinker was responding to two phenomena in American academia in the 1990’s, the first was political correctness, and the second was the resistance to, or even the unwillingness to engage with, the rising fields of sociobiology and evolutionary psychology by many members of the academy.

I was a college student in the 1990s, so I know what Pinker means by political correctness. There was a general sense that any willingness to engage with conservative ideas or traditional morality somehow tainted one in the eyes of professors as a closet fascists, racists, misogynist, or homophobe. I think the reason for this is that many participants in the revolutionary 1960’s, unable to really change American society through the government, found themselves in the academy, something that encouraged groupthink, and given the resurgence of conservatism in the larger American society at the time led to a sense of siege that left made academics particularly prickly whenever such ideas found were expressed by students. Both the retirement of this generation of professors, and the obvious traction their ideas now have in the larger society seem likely to end this state of affairs.

But the primary thing Pinker is out to defend in his Blank Slate is the attitude towards the resurgence of the human sciences of sociobiology and evolutionary psychology a

resurgence that began with the publication of E.O. Wilson’s Sociobiology the New Synthesis in 1975. Academics, most notably the late Stephen Jay Gould were particularly concerned with any attempts to explain human nature in terms of evolution, both because it appeared to justify an oppressive status quo and because of the association of these ideas with both past US racism, and the genocidal nature of the Nazi regime, an argument Gould and others made in their 1975 essay, Against Sociobiology.

This overreaction to Wilson is understandable given the historical context- it was, after all, only 30 years since the defeat of the Nazis, and less than that from the victories of both the Civil and the Woman’s’ Rights Movement. Again, time seems to have ironed out these differences and sociobiology and evolutionary psychology have joined the rank of mundane social sciences- though in some sense the dystopian anxieties of Gould and others regarding these fields might ultimately prove to have some basis.

Pinker, in some ways correctly, associates utopia with the idea of the human mind and character as a blank slate, and sets out in his work of the same title to disprove that view of human nature. Pinker divides the intellectual world into two camps- those with what he calls a “Tragic Vision” which is conservative and sees human nature as largely unchangeable and those with a “Utopian Vision” who see human nature as a “blank slate” upon which what humans are can be redefined. He himself thinks that science backs up the Tragic Vision, and therefore sides with it, writing: