The technological ecosystem in which political power operates tends to mark out the possibility space for what kinds of political arrangements, good and bad, exist within that space. Orwell’s Oceania and its sister tyrannies were imagined in what was the age of big, centralized media. Here the Party had under its control not only the older printing press, having the ability to craft and doctor, at will, anything created using print from newspapers, to government documents, to novels. It also controlled the newer mediums of radio and film, and, as Orwell imagined, would twist those technologies around backwards to serve as spying machines aimed at everyone.

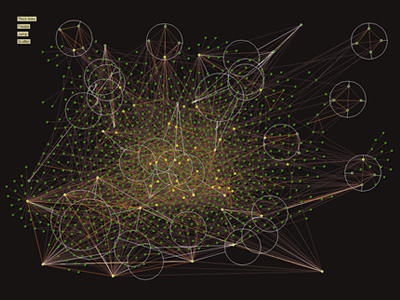

The questions, to my knowledge, Orwell never asked was what was the Party to do with all that data? How was it to store, sift through, make sense of, or locate locate actual threats within it the yottabytes of information that would be gathered by recording almost every conversation, filming or viewing almost every movement, of its citizens lives? In other words, the Party would have ran into the problem of Big Data. Many of Orwellian developments since 9/11 have come in the form of the state trying to ride the wave of the Big Data tsunami unleashed with the rise of the internet, an attempt create it’s own form of electronic panopticon.

In their book Top Secret America: The Rise of the New American Security State, Dana Priest, and ,William Arkin, of the Washington Post present a frightening picture of the surveillance and covert state that has mushroomed in the United States since 9/11. A vast network of endeavors which has grown to dwarf, in terms of cummulative numbers of programs and operations, similar efforts, during the unarguably much more dangerous Cold War. (TS 12)

Theirs’ is not so much a vision of an America of dark security services controlled behind the scenes by a sinister figure like J. Edgar Hoover, as it is one of complexity gone wild. Priest and Arkin paint a picture of Top Secret America as a vast data sucking machine, vacuuming up every morsel of information with the intention of correctly “connecting the dots”, (150) in the hopes of preventing another tragedy like 9/11.

So much money was poured into intelligence gathering after 9/11, in so many different organizations, that no one, not the President, nor the Director of the CIA, nor any other official has a full grasp of what is going on. The security state, like the rest of the American government, has become reliant on private contractors who rake in stupendous profits. The same corruption that can be found elsewhere in Washington is found here. Employees of the government and the private sector spin round and round in a revolving door between the Washington connections brought by participation in political establishment followed by big-time money in the ballooning world of private security and intelligence. Priest quotes one American intelligence official who had the balls to describe the insectous relationship between government and private security firms as “a self-licking ice cream cone”. (TS 198)

The flood of money that inundated the intelligence field in after 9/11 has created what Priest and Arkin call an “alternative geography” companies doing covert work for the government that exist in huge complexes, some of which are large contain their very own “cities”- shopping centers, athletic facilities, and the like. To these are added mammoth government run complexes some known and others unknown.

Our modern day Winston Smiths, who work for such public and private intelligence services, are tasked not with the mind numbing work of doctoring history, but with the equally superfluous job of repackaging the very same information that had been produced by another individual in another organization public or private each with little hope that they would know that the other was working on the same damned thing. All of this would be a mere tragic waste of public money that could be better invested in other things, but it goes beyond that by threatening the very freedoms that these efforts are meant to protect.

Perhaps the pinnacle of the government’s Orwellian version of a Google FaceBook mashup is the gargantuan supercomputer data center in Bluffdale Nevada built and run by the premier spy agency in the age of the internet- the National Security Administration or NSA. As described by James Bamford for Wired Magazine:

In the process—and for the first time since Watergate and the other scandals of the Nixon administration—the NSA has turned its surveillance apparatus on the US and its citizens. It has established listening posts throughout the nation to collect and sift through billions of email messages and phone calls, whether they originate within the country or overseas. It has created a supercomputer of almost unimaginable speed to look for patterns and unscramble codes. Finally, the agency has begun building a place to store all the trillions of words and thoughts and whispers captured in its electronic net.

It had been thought that domestic spying by the NSA, under a super-secret program with the Carl Saganesque name, Stellar Wind, had ended during the G.W. Bush administration, but if the whistleblower, William Binney, interviewed in this chilling piece by Laura Poitras of the New York Times, is to be believed, the certainly unconstitutional program remains very much in existence.

The bizarre thing about this program is just how wasteful it is. After all, don’t private companies, such as FaceBook and Google not already possess the very same kinds of data trails that would be provided by such obviously unconstitutional efforts like those at Bluffdale? Why doesn’t the US government just subpoena internet and telecommunications companies who already track almost everything we do for commercial purposes? The US government, of course, has already tried to turn the internet into a tool of intelligence gathering, most notably, with the stalled Cyber Intelligence Sharing and Intelligence Act, or CISPA , and perhaps it is building Bluffdale in anticipation that such legislation will fail, that however it is changed might not be to its liking, or because it doesn’t want to be bothered with the need to obtain warrants or with constitutional niceties such as our protection against unreasonable search and seizure.

If such behemoth surveillance instruments fulfill the role of the telescreens and hidden microphones in Orwell’s 1984, then the role the only group in the novel whose name actually reflects what it is- The Spies – children who watch their parents for unorthodox behavior and turn them in, is taken today by the American public itself. In post 9/11 America it is, local law enforcement, neighbors, and passersby who are asked to “report suspicious activity”. People who actually do report suspicious activity have their observations and photographs recorded in an ominous sounding data base that Orwell himself might have named called The Guardian. (TS 144)

As Priest writes:

Guardian stores the profiles of tens of thousands of Americans and legal residents who are not accused of any crime. Most are not even suspected of one. What they have done is appear, to a town sheriff, a traffic cop, or even a neighbor to be acting suspiciously”. (TS 145)

Such information is reported to, and initially investigated by, the personnel in another sort of data collector- the “fusion centers” which had been created in every state after 9/11.These fusion centers are often located in rural states whose employees have literally nothing to do. They tend to be staffed by persons without intelligence backgrounds, and who instead hailed from law enforcement, because those with even the bare minimum of foreign intelligence experience were sucked up by the behemoth intelligence organizations, both private and public, that have spread like mould around Washington D.C.

Into this vacuum of largely non-existent threats came “consultants” such as Montijo Walid Shoebat, who lectured fusion center staff on the fantastical plot of Muslims to establish Sharia Law in the United States. (TS 271-272). A story as wild as the concocted boogeymen of Goldstein and the Brotherhood in Orwell’s dystopia.

It isn’t only Mosques, or Islamic groups that find themselves spied upon by overeager local law enforcement and sometimes highly unprofessional private intelligence firms. Completely non-violent, political groups, such as ones in my native Pennsylvania, have become the target of “investigations”. In 2009 the private intelligence firm the Institute for Terrorism Research and Response compiled reports for state officials on a wide range of peaceful political groups that included: “The Pennsylvania Tea Party Patriots Coalition, the Libertarian Movement, anti-war protesters, animal-rights groups, and an environmentalist dressed up as Santa Claus and handing out coal-filled stockings” (TS 146). A list that is just about politically broad enough to piss everybody off.

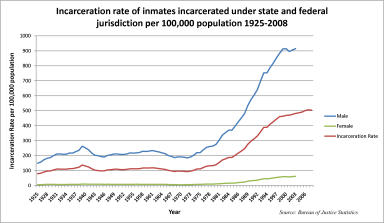

Like the fusion centers, or as part of them, data rich crime centers such as the Memphis Real Time Crime Center are popping up all over the United States. Local police officers now suck up streams of data about the environments in which they operate and are able to pull that data together to identify suspects- now by scanning licence plates, but soon enough, as in Arizona, where the Maricopa County Sheriff’s office was creating up to 9,000 biometric, digital profiles a month (TS 131) by scanning human faces from a distance.

Sometimes crime centers used the information gathered for massive sweeps arresting over a thousand people at a clip. The result was an overloaded justice and prison system that couldn’t handle the caseload (TS 144), and no doubt, as was the case in territories occupied by the US military, an even more alienated and angry local population.

From one perspective Big Data would seem to make torture more not less likely as all information that can be gathered from suspects, whatever their station, becomes important in a way it wasn’t before, a piece in a gigantic, electronic puzzle. Yet, technological developments outside of Big Data, appear to point in the direction away from torture as a way of gathering information.

“Controlled torture”, the phrase burns in my mouth, has always been the consequence of the unbridgeable space between human minds. Torture attempts to break through the wall of privacy we possess as individuals through physical and mental coercion. Big Data, whether of the commercial or security variety, hates privacy because it gums up the capacity to gather more and more information for Big Data to become what so it desires- Even Bigger Data. The dilemma for the state, or in the case of the Inquisition, the organization, is that once the green light has been given to human sadism it is almost impossible to control it. Torture, or the knowledge of torture inflicted on loved ones, breeds more and more enemies.

Torture’s ham fisted and outwardly brutal methods today are going hopelessly out of fashion. They are the equivalent of rifling through someone’s trash or breaking into their house to obtain useful information about them. Much better to have them tell you what you need to know because they “like” you.

In that vein, Priest describes some of the new interrogation technologies being developed by the government and private security technology firms. One such technology is an “interrogation booth” that contain avatars with characteristics (such as an older Hispanic woman) that have been psychologically studied to produce more accurate answers from those questioned. There are ideas to replace the booth with a tiny projector mounted on a soldier’s or policeman’s helmet to produce the needed avatar at a moments notice. There was also a “lie detecting beam” that could tell- from a distance- whether someone was lying by measuring miniscule changes on a person’s skin. (TS 169) But if security services demand transparency from those it seeks to control they offer up no such transparency themselves. This is the case not only in the notoriously secretive nature of the security state, but also in the way the US government itself explains and seeks support for its policies in the outside world.

Orwell, was deeply interested in the abuse of language, and I think here too, the actions of the American government would give him much to chew on. Ever since the disaster of the war in Iraq, American officials have been obsessed with the idea of “soft-power”. The fallacy that resistance to American policy was a matter of “bad messaging” rather than the policy itself. Sadly, this messaging was often something far from truthful and often fell under what the government termed” Influence operations” which, according to Priest:

Influence operations, as the name suggests, are aimed at secretly influencing or manipulating the opinions of foreign audiences, either on an actual battlefield- such as during a feint in a tactical battle- or within civilian populations, such as undermining support for an existing government of terrorist group (TS 59)

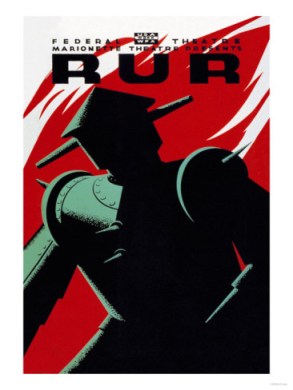

Another great technological development over the past decade has been the revolution in robotics, which like Big Data is brought to us by the ever expanding information processing powers of computers, the product of Moore’s Law.

Since 9/11 multiple forms of robots have been perfected, developed, and deployed by the military, intelligence services and private contractors only the most discussed and controversial of which have been flying drones. It is with these and other tools of covert warfare, such as drones, and in his quite sweeping understanding and application of executive power that President Obama has been even more Orwellian than his predecessor.

Obama may have ended the torture of prisoners captured by American soldiers and intelligence officials, and he certainly showed courage and foresight in his assassination of Osama Bin Laden, a fact by which the world can breathe a sigh of relief. The problem is that he has allowed, indeed propelled, the expansion of the instruments of American foreign policy that are largely hidden from the purview and control of the democratic public. In addition to the surveillance issues above, he has put forward a sweeping and quite dangerous interpretation of executive power in the forms of indefinite detention without trial found in the NDAA, engaged in the extrajudicial killings of American citizens, and asserted the prerogative, questionable under both the constitution and international law, to launch attacks, both covert and overt, on countries with which the United States is not officially at war.

In the words of Conor Friedersdorf of the Atlantic writing on the unprecedented expansion of executive power under the Obama administration and comparing these very real and troubling developments to the paranoid delusions of right-wing nuts, who seem more concerned with the fantastical conspiracy theories such as the Social Security Administration buying hollow-point bullets:

… the fact that the executive branch is literally spying on American citizens, putting them on secret kill lists, and invoking the state secrets privilege to hide their actions doesn’t even merit a mention. (by the right-wing).

Perhaps surprisingly, the technologies created in the last generation seem tailor made for the new types of covert war the US is now choosing to fight. This can perhaps best be seen in the ongoing covert war against Iran which has used not only drones but brand new forms of weapons such the Stuxnet Worm.

The questions posed to us by the militarized versions of Big Data, new media, Robotics, and spyware/computer viruses are the same as those these phenomena pose in the civilian world: Big Data; does it actually provide us with a useful map of reality, or instead drown us in mostly useless information? In analog to the question of profitability in the economic sphere: does Big Data actually make us safer? New Media, how is the truth to survive in a world where seemingly any organization or person can create their own version of reality. Doesn’t the lack of transparency by corporations or the government give rise to all sorts of conspiracy theories in such an atmosphere, and isn’t it ultimately futile, and liable to backfire, for corporations and governments to try to shape all these newly enabled voices to its liking through spin and propaganda? Robotics; in analog to the question of what it portends to the world of work, what is it doing to the world of war? Is Robotics making us safer or giving us a false sense of security and control? Is it engendering an over-readiness to take risks because we have abstracted away the very human consequences of our actions- at least in terms of the risks to our own soldiers. In terms of spyware and computer viruses: how open should our systems remain given their vulnerabilities to those who would use this openness for ill ends?

At the very least, in terms of Big.Data, we should have grave doubts. The kind of FaceBook from hell the government has created didn’t seem all that capable of actually pulling information together into a coherent much less accurate picture. Much like their less technologically enabled counterparts who missed the collapse of the Eastern Bloc and fall of the Soviet Union, the new internet enabled security services missed the world shaking event of the Arab Spring.

The problem with all of these technologies, I think, is that they are methods for treating the symptoms of a diseased society, rather than the disease itself. But first let me take a detour through Orwell vision of the future of capitalist, liberal democracy seen from his vantage point in the 1940s.

Orwell, and this is especially clear in his essay The Lion and the Unicorn, believed the world was poised between two stark alternatives: the Socialist one, which he defined in terms of social justice, political liberty, equal rights, and global solidarity, and a Fascist or Bolshevist one, characterized by the increasingly brutal actions of the state in the name of caste, both domestically and internationally.

He wrote:

Because the time has come when one can predict the future in terms of an “either–or”. Either we turn this war into a revolutionary war (I do not say that our policy will be EXACTLY what I have indicated above–merely that it will be along those general lines) or we lose it, and much more besides. Quite soon it will be possible to say definitely that our feet are set upon one path or the other. But at any rate it is certain that with our present social structure we cannot win. Our real forces, physical, moral or intellectual, cannot be mobilised.

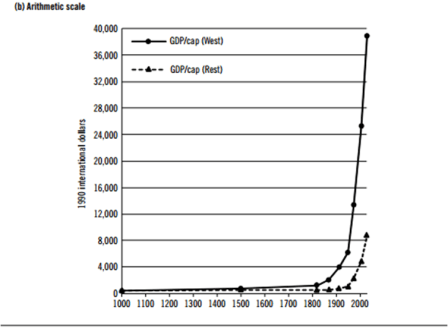

It is almost impossible for those of us in the West who have been raised to believe that capitalist liberal democracy is the end of the line in terms of political evolution to remember that within the lifetimes of people still with us (such as my grandmother who tends her garden now in the same way she did in the 1940’s) this whole system seemed to have been swept up into the dustbin of history and that the future lie elsewhere.

What the brilliance of Orwell missed, the penetrating insight of Aldous Huxley in his Brave New World caught: that a sufficiently prosperous society would lull it’s citizens to sleep, and in doing so rob them both of the desire for revolutionary change and their very freedom.

As I have argued elsewhere, Huxley’s prescience may depend on the kind of economic growth and general prosperity that was the norm after the Second World War. What worries me is that if the pessimists are proven correct, if we are in for an era of resource scarcity, and population pressures, stagnant economies, and chronic unemployment that Huxley’s dystopia will give way to a more brutal Orwellian one.

This is why, no matter who wins the presidential election in November, we need to push back against the Orwellian features that have crept upon us since 9/11. The fact is we are almost unaware that we building the architecture for something truly dystopian and should pause to think before it is too late.

To return to the question of whether the new technologies help or hurt here: It is almost undeniable that all of the technological wonders that have emerged since 9/11 are good at treating the symptoms of social breakdown, both abroad and at home. They allow us to kill or capture persons who would harm largely innocent Americans, or catch violent or predatory criminals in our own country, state, and neighborhood. Where they fail is in getting to the actual root of the disease itself.

American would much better serve its foreign policy interest were it to better align itself with the public opinion of the outside world insofar as we were able to maintain our long term interests and continue to guarantee the safety of our allies. Much better than the kind of “information operation” supported by the US government to portray a corrupt, and now deposed, autocrat like Yemen’s Abdullah Saleh as “an anti-corruption activist”, would be actual assistance by the US and other advanced countries in…. I duknow… fighting corruption. Much better Western support for education and health in the Islamic world that the kinds of interference in the internal political development of post-revolutionary Islamic societies driven by geopolitical interest and practiced by the likes of Iran and Saudi Arabia.

This same logic applies inside the United States as well. It is time to radically roll back the Orwellian advances that have occurred since 9/11. The dangers of the war on terrorism were always that they would become like Orwell’s “continuous warfare”, and would perpetually exist in spite, rather than because of the level of threat. We are in danger of investing so much in our security architecture, bloated to a scale that dwarfs enemies, which we have blown up in our own imaginations into monstrous shadows, that we are failing to invest in the parts of our society that will actually keep us safe and prosperous over the long-term.

In Orwell’s Oceania, the poor, the “proles” were largely ignored by the surveillance state. There is a danger here that with the movement of what were once advanced technologies into the hands of local law enforcement: drones, robots, biometric scanners, super-fast data crunching computers, geo-location technologies- that domestically we will move even further in the direction of treating the symptoms of social decay, rather than dealing with the underlying conditions that propel it.

The fact of the matter is that the very equality, “the early paradise”, a product of democratic socialism and technology, Orwell thought was at our fingertips has retreated farther and farther from us. The reasons for this are multiple; To name just a few: financial concentration, automation, the end of “low hanging fruit” and their consequent high growth rates brought by industrialization,the crisis of complexity and the problem of ever more marginal returns. This retreat, if it lasts, would likely tip the balance from Huxley’s stupification by consumption to Orwell’s more brutal dystopia initiated by terrified elites attempting to keep a lid on things.

In a state of fear and panic we have blanketed the world with a sphere of surveillance, propaganda and covert violence at which Big Brother himself would be proud. This is shameful, and threatens not only to undermine our very real freedom, but to usher in a horribly dystopian world with some resemblance to the one outlined in Orwell’s dark imaginings. We must return to the other path.