It was a time when the greatest power the world had yet known suffered an attack on its primary city which seemed to signal the coming of an age of unstoppable decline.The once seemingly unopposable power no longer possessed control over its borders,it was threatened by upheaval in North Africa, unable to bring to heel the stubborn Iranians, or stem its relative decline. It was suffering under the impact of climate change, its politics infected with systemic corruption, its economy buckling under the weight of prolonged crisis.

Blame was sought. Conservatives claimed the problem lie with the abandonment of traditional religion, the rise of groups they termed “atheists” especially those who preached the possibility of personal immortality. One of these “atheists” came to the defense of the immortalist movement arguing not so much that the new beliefs were not responsible for the great tribulations in the political world, but that such tribulations themselves were irrelevant. What counted was the prospect of individual immortality and the cosmic view- the perspective that held only that which moved humanity along to its ultimate destiny in the universe was of true importance. In the end it would be his movement that survived after the greatest of empires collapsed into the dust of scattered ruins….

Readers may be suspicious that I am engaged in a sleight of hand with such an introduction, and I indeed am; however much the description above resembles the United States of the early 21st century, I am in fact describing the Roman Empire of the 400s C.E. The immortalists here are not contemporary transhumanists or singularitarians but early Christians whom many pagans considered not just dangerously innovative, but also, because they did not believe in the pagan gods, were actually labeled atheists- which is where we get the term. The person who came to the defense of the immortalists and who laid out the argument that it was this personal immortality and the cosmic view of history that went with it that counted rather than the human drama of politics history and culture was not Ray Kurzweil or any other figure of the singularitarian or transhumanist movements, but Augustine who did so in his work The City of God.

Now, a book with such a title not to mention one written in the 400s might not seem like it would be relevant to any secular 21st century person contemplating our changing relationship with death and time, but let me try to show you why such a conclusion would be false. When Augustine wrote The City of God he was essentially arguing for a new version of immortality. For however much we might tend to think the dream of immortality was invented to assuage human fears of personal death the ancient pagans (and the Jews for that matter) had a pretty dark version of it. Or, as Achilles said to Odysseus:

“By god, I’d rather slave on earth for another man—some dirt-poor tenant farmer who scrapes to keep alive—than rule down here over all the breathless dead.”

For the pagans, the only good form of immortality was that brought by fame here on earth. Indeed, in later pagan versions of paradise which more resembled the Christian notion “heaven” was reserved for the big-wigs. The only way to this divinity was to do something godlike on earth in the service of one’s city or the empire. Augustine signaled a change in all that.

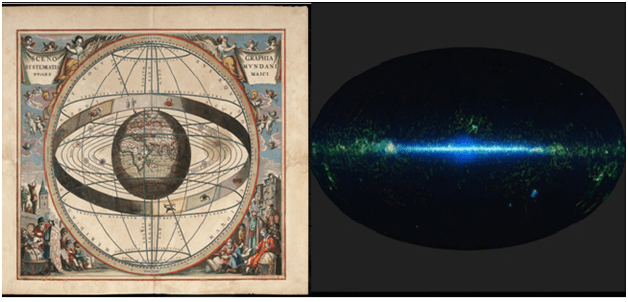

Christianity not only upended the pagan idea of immortality granting it to everybody- slaves no less than kings, but, according to Augustine, rendered the whole public world the pagans had found so important irrelevant. What counted was the fact of our immortality and the big picture- the fate that God had in store for the universe, the narrative that got us to this end. The greatest of empires could rise and fall what they will, but they were nothing next to the eternity of our soul our God and his creation. Rome had been called the eternal city- but it was more mortal than the soul of its most powerless and insignificant citizen.

Of course, from a secular perspective the immortality that Augustine promised was all in his head. If anything, it served as the foundation not for immortal human beings nor for a narrative of meaning that stretched from the beginning to the the end of time- but for a very long lived institution- the Catholic Church- that has managed to survive for two millennia, much longer indeed than all the empires and states that have come and gone in this period, and who knows, if it gets its act together may even survive for another thousand years.

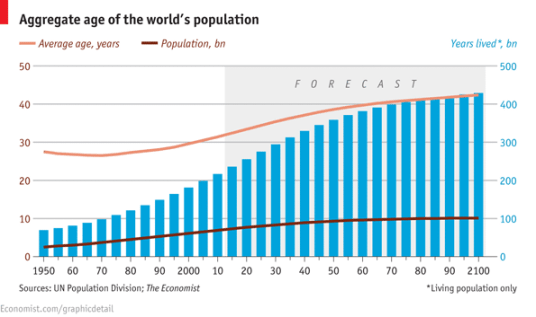

All of this might seem far removed from contemporary concerns until one realizes the extent to which we ourselves are and will be confronting a revolutionary change in our relationship to both death and time akin to and of a more real and lasting impact than the one Augustine wrestled with. No matter what way one cuts it our relationship to death has changed and is likely to continue to change. The reason for this is that we are now living so long, and suspect we might be able to live much longer. A person in the United States in 1913 could be expected to live just shy of the ripe old age of 53. The same person in 2013 is expected to live within a hair’s breath of 79. In this as in other departments the US has a ways to go. The people of Monaco, the country with the highest life expectancy, live on average a decade longer.

How high can such longevity go? We have no idea. Some, most famously Aubrey de Gray, think there is no theoretical limit to how long a human being can live if we get the science right. We are likely some ways from this, but given the fact that such physical immortality, or something close to it, does not seem to violate any known laws of nature, then if there is not something blocking its appearance, say complexity, or more ominously, expense, we are likely to see something like the defeat of death if not in this century then in some further future that is not some inconceivable distance from us.

This might be a good time,then, to start asking questions about our relationship to death and time, and how both relate to the societies in which we live. Even if immortality remains forever outside our grasp by exploring the topic we might learn something important about death time and ourselves in the process. It was exactly these sorts of issues that Augustine was out to explore.

What Augustine argued in The City of God was that societies, in light of eternal life had nothing like the meaning we were accustomed to giving them. What counted was that one lead a Christian life (although as a believer in predestination Augustine really thought that God would make you do this if he wanted to). The kinds of things that counted in being a good pagan were from Augustine’s standpoint of eternity little but vanity. A wealthy pagan might devote money to his city, pay for a public festival, finance the construction of a theater or forum. Any pagan above the level of a slave would likely spend a good deal of time debating the decisions of his city, take concern in its present state and future prospects. As young men it would be the height of honor for a pagan to risk his life for his city. The pagan would do all these things in the hope that they might be remembered. In this memory and in the lives of his descendants lie the possibility of a good version of immortality as opposed to the wallowing in the darkness of Hades after death. Augustine countered with a question that was just as much a charge: What is all this harking after being remembered compared to the actual immortality offered by Christ?

There are lengths in the period of longevity far in advance of what human beings now possess where the kinds of tensions between the social and pagan idea of immortality and the individual Christian idea of eternal life that Augustine explored do not yet come into full force. I think Vernor Vinge is onto something (@36 min) when he suggests that extending the human lifespan into the range of multiple centuries would be extremely beneficial for both the individual and society. Longevity on the order of 500 years would likely anchor human beings more firmly in time. In terms of the past such a lifespan would give us a degree of wisdom we sorely lack, allowing us to avoid almost inevitably repeating the mistakes of a prior age once those with personal experience of such mistakes or tragedies are no longer around to offer warnings or even who we could ask- as was the case with our recent financial crisis once most of those who had lived through the Great Depression as adults had passed.

500 years of life would also likely orient us more strongly towards the future. We could not only engage in very long term projects of all sorts that are impossible today given our currently limited number of years, we would actually be invested in making sure our societies weren’t making egregious mistakes- such as changing the climate- whose full effects wouldn’t be felt until centuries in the future. These longer-term horizons, at least when compared to what we have now, would cease being abstractions because it would no longer be our great grandchildren that lived there but us.

The kinds of short-termism that now so distort the politics of the United States might be less likely in a world where longevity was on the order of several centuries. Say what one might about the Founding Fathers, but they certainly took the long-term future of the United States into account and more importantly established the types of lasting institutions that would make that future a good one. Adams and Jefferson created our oldest and perhaps most venerable cultural institution- The Library of Congress. Jefferson founded the University of Virginia. Later American political figures, such as Lincoln, not only did the difficult work of keeping the young nation intact, but developed brillant institutions such as Land-Grant Colleges to allow learning and technological know-how to penetrate the countryside. In addition to all this, the United States invented the idea of national parks, the hope being to preserve for centuries or even millennia the natural legacy of North America.

Where did we get this long term perspective and where did it go? Perhaps it was the afterglow of the Enlightenment’s resurrection of pagan civic virtues. We certainly seem no longer capable of taking such a long view- the light has gone out. Politicians today seem unable to craft policy that will deal with issues beyond the next election cycle let alone respond to issues or foster public investments that will play out or come to fruition in the days of their grandchildren. Individuals seem to have lost some of the ability to think beyond their personal life span, so perhaps, just perhaps, the solution is to increase the lifespan of individuals themselves.

Thinking about time, especially long stretches of time, and how it runs into the annihilation of death, seems to inevitably lead to reflections about human society and the relationship of the young with the old. Freud might have been right when he reduced the human condition to sex and death for something in the desire to leave a future legacy inspired by death does seem to resemble sex- or rather procreation- allowing us to pass along imperfect “copies” of ourselves even if, when it comes to culture, these copies are very much removed from us indeed.

This bridging of the past and the future might even be the ultimate description of what societies and institutions are for. That is, both emerge from our confrontation with time and are attempts to win this conflict by passing information, or better, knowledge, from the past into the future in a similar way to how this is accomplished biologically in the passing on of genes through procreation. The common conception that innovation most likely emerges from youth, if it is true, might be as much a reflection of the fact that the young have quite simply not been here long enough to receive this full transmission and are on that account the most common imperfect “copies” of the ideas of their elders. Again, like sex, the transmission of information from the old to the new generation allows novel combinations and even mutations which if viable are themselves passed along.

It’s at least an interesting question to ask what might happen to societies and institutions that act as our answer to the problem of death if human beings lived for what amounted to forever? The conclusion Augustine ultimately reached is once you eliminate death you eliminate the importance of the social and political worlds. Granting the individual eternity means everything that now grips our attention become little but fleeting Mayflies in the wind. We might actually experience a foretaste of this, some say we are right now, even before extreme periods of longevity are achieved if predictions of an ever accelerating change in our future bear fruit. Combined with vastly increased longevity accelerating change means the individual becomes the only point in history that actually stands still. Whole technological regimes, cultures, even civilizations rise and fall under the impact of technological change while only the individual- in terms of a continuous perspective since birth or construction- remains. This would entail a reversal of all of human history to this point where it has been the institutions that survive for long periods of time while the individuals within them come and go. We therefore can’t be sure what many of the things we take as mere background to our lives today- our country, culture, idea of history, in such circumstances even look like.

What might this new relationship between death and technological and social change do to the art and the humanities, or “post-humanities”? The most hopeful prediction regarding this I have heard is again Vinge, though I can not find the clip. Vinge discussed the possibility of extended projects that are largely impossible given today’s average longevity. Artists and writers probably have an intuitive sense for what he means, but here are some examples- though they are mine not his. In a world of vastly increased longevity a painter could do a flower study of every flower on earth or portraits of an entire people. A historian could write a detailed history of a particular city from the palaeolithic through the present in pain staking detail, a novelist could really create a whole alternative imagined world filled with made up versions of memoirs, religious texts, philosophical works and the like. Projects such as these are impossible given our limited time here and on account of the fact that there are many more things to care about in life besides these creations.

Therefore, vastly increased longevity might mean that our greatest period of cultural creation- the world’s greatest paintings, novels, historical works and much else besides will be found in the human future rather than its past. Increased longevity would also hopefully open up scientific and technological projects that were centuries rather than decades in the making such as the recovery of lost species and ecosystems or the move beyond the earth. One is left wondering, however, the extent to which such long term focus will be preserved in light of an accelerating speed of change.

A strange thing is happening in that while the productive lifespan of an individual artist is increasing- so much for The Who’s “hope I die before I get old”– the amount of time it takes an artist to create any particular work is, through technological advancement, likely decreasing. This should lead to more artistic productivity, but one is left to ponder what any work of art would mean if the dreams of accelerating technological change come true at precisely the same time that human longevity is vastly increased? Here is what I mean: when one tries to imagine a world where human beings live for lengths of time that are orders of magnitude longer than those today and where technological change proves to be in a persistently accelerating state what you get is a world that is so completely transformed within the course of a generation that it bears as much resemblance to the generation before it as we do to the ancient Greeks. What does art mean in such a context where the world it addresses no longer exists not long after it has been made?

This same condition of fleetingness applies to every other aspect of life as well from the societies we live in down to the relationships with those we love. It was Augustine’s genius to realize that if one looks at life from the perspective of individual eternity it is not the case that everything else becomes immortal as well, but that the mortality of everything we are not becomes highlighted.

This need not spell the end of all those things we currently take as the vastly important long lasting background of our mortal lives, but it will likely change their character. To use a personal story, cultural and political creations and commitments in the future might still be meaningful in the sense that my Nana’s flower garden is meaningful. My Nana just turned 91 and still manages to plant and care for her flowers that bloom in spring only to disappear until brought back by her gentle and wise hands at the season’s return. Perhaps the longer we live the more the world around us will get its meaning not through its durability but as a fleeting beauty brought forth because we cared enough to stop for a moment to orchestrate and hold still, if even for merely a brief instant, time’s relentless flow.