Imagine, if you will, the following scenario taking place today: A, to this point failed, novelist writes an updated version of Rip-Van Winkle where his protagonists falls asleep to be awakened a century or so in the future. Through this protagonist the reader is then given a tour through a future in which the social problems of his own day have been completely resolved, the linchpin of their solution being a new and revolutionary economic system. To add a human element to the story the protagonist finds love in this future-world in the form of the great-great granddaughter of the woman he loved a century in the past, a love that his coma had tragically stopped short.

My guess is that today such a novel would be judged, though not in these words, a mere “ fairy tale of social felicity” (Bellamy) If it was lucky, it would find itself on the shelf at Barnes and Noble next to works by J.R. Tolkien, or J.K. Rowling. What is most unlikely is that the book would become the third largest best seller in US history, and that it would spawn the formation of “clubs” throughout the country where professionals: doctors, lawyers, professors, and scientists would gather round to discuss whether the book offered a blueprint for solving society’s economic and political ills. It would seem out of the ordinary for such a book today to engender actual debate among political theorists, let alone in the form of other utopian novels that tried to play out rival versions of the future. Nor would it seem likely that real-world revolutionaries would take such a piece of pulp-fiction seriously. I mean Rip-Van Winkle? Come on!

And yet, all these things were precisely what happened to Edward Bellamy’s novel Looking Backward: 2000-1887. The novel tells the story of Julian West who falls into a coma like sleep in 1887 and wakes up in the year 2000. The world in which Julian awakes is one which has solved the endemic problems of capitalism: class war, economic instability, and inequality and constitutes a socialist utopia where the means of production are under the centralized control of the federal government. Something Bellamy, almost a half-century before Hitler would steal the phrase, called “national socialism”.

Bellamy got at least the general outlines of some future economic and technological developments right, though his Victorianism gives his vision of the future a decidedly steampunk feel. He imagines goods being bought in centralized warehouses tied together in a complex, super-fast, and efficient nation-spanning logistics system: a system managers at Wal- Mart and Amazon would certainly recognize. Bellamy envisions a kind of telephone/radio that would allow live performances to be piped in from anywhere in the country to anyone’s home. He imagines all purchases being made with something like a credit card. Although, because this income comes from the government, it has a stronger resemblance to the “Access Cards” given to the needy to purchase food, medical care, and other necessities.

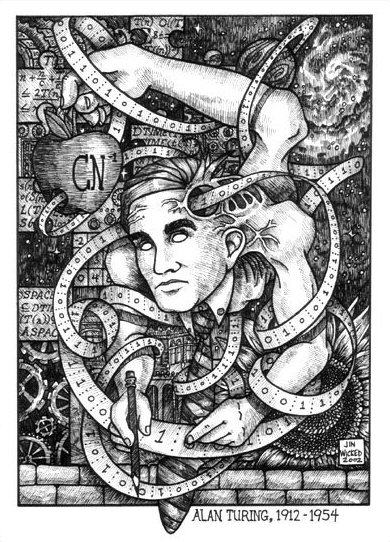

What meaning this Victorian tale could have for today is discussed in an excellent recent essay in Lapham’s Quarterly by, Ben Tarnoff, entitled “Magical Thinking”. (The picture above is taken from that article). Tarnoff thinks we can take away two things by considering Looking Backward. The first is how the novel, and the spirit which it represents, can be contrasted with our own anti-utopian sentiments, the product he thinks, of our encounter with the most horrific versions of “utopianism” in the early 20th century. The second is that Tarnoff sees the novel as emerging out of the problems of capitalism. Problems that Bellamy in his own way was trying to solve, and which we ourselves relate to in a much different way.

Rather than having ever solved those problems Tarnoff believes we have come to accept them:

The twenty-first century bears little resemblance to Bellamy’s future; the closer comparison would be to his present, to the late nineteenth century that the hero of his novel happily escapes. This was a society defined by tremendous income inequality, financial uncertainty, sleazy politics—in other words, much like our own. The contradictions of modern capitalism haven’t resolved themselves, as Bellamy assumed. Rather, they’ve become deeply embedded in American life, and the new economic world created after the Civil War has come to feel so natural, so inescapable, that even many of its staunchest critics have trouble imagining an alternative.

I agree with Tarnoff’s first point, that our ability to imagine alternatives is stunted compared to the very creative era in which Bellamy lived, but I want to qualify Tarnoff’s second point that this lack of imagination can be explained by the fact that we’ve somehow come to live with the kinds of problems Bellamy thought just couldn’t go on without giving rise to the demand for an alternative.

In our own era utopian science-fiction and political philosophy, let alone economic theory have seemingly completely parted company. There are exceptions to this- Ayn Rand has a cult following among libertarians, and Ursula Le Guin has captured the hearts of anarchists, but these are exceptions. (If anyone has other examples please, please share in the comments section).

The very word utopian is a kind of intellectual insult that means you just aren’t serious about what you are saying and need better acquaintance with the limiting reality of facts.

Taroff believes we have come to this stunted imagination because we have come to accept the kinds of economic and political conditions that Bellamy found intolerable, but this position becomes somewhat less clear when we take the longer view.

Bellamy was writing during a period of intense economic dislocation, labor unrest, and stagnating economic growth that began during the 1870’s and is known as the Long Depression. In her book Imperialism (book 2 of the Origins of Totalitarianism) the political theorist, Hannah Arendt, credits this economic crisis with the great wave of largely European imperialism at the end of the 19th century. Imperialism didn’t solve the economic crisis, and what occurred instead is that the crisis was met by a whole series of measures starting in the United States to solve some of the the endemic problems of “late capitalism”, by for instance, preventing the rise of monopolies.

Yet, truly revolutionary forces pushing towards an alternative economic system to capitalism would only come to the fore in the aftermath of the First World War, in the collapsed Russian Empire, forces that would gain traction in Western countries with the collapse of the world economy in the Great Depression. Thereafter, public policy, even in a society convinced of the virtues of free-enterprise, such as the United States, would push in the direction of a “tamed” capitalism and a more equal society in which the abuses, instabilities and inequality of capitalism were contained. Technological and demographic developments would dovetail with these efforts and result in an unprecedented period of widespread prosperity and economic calm, though perhaps also one lacking economic innovation, and certainly one of endemic inflation and general stagnation.

When this age of growth began to peter-out in the 1970s the logic seemed to be that the way back to more innovative and less inflationary growth would be to return to at least some of the conditions of capitalism in the era of Bellamy: a return to less regulated markets, tougher competition between labor- including American workers with lower paid workers abroad- a less generous welfare-state, and an acceptance of inequality as the byproduct of success in economic competition.

It should not come as a surprise at all that the kind of utopianism found in the 1950s and 60s wasn’t really proposing an alternative form of society and economics, but instead was a super-technological, Popular Mechanics, version of the consumer society that had, after all, only just come into being after the horrors of Depression and War. Nor, should it seem shocking that utopianism, again as a serious alternative version of the current economic and political order, was so silent after the 1970s. The spirit of the times was that it was our utopian aspirations that had gotten us into the mess we were in in the first place.

Christian Caryl, in an excellent article for the magazine Foreign Policy, 1979: The Great Backlash offers the argument that the contemporary era, whatever we might choose to call it, should be dated not from the end of the Cold War or 9/11, but the year 1979. Caryl pools together some of the most seemingly different cast of characters in modern history: Margaret Thatcher, Deng Zhou Ping (the post Mao premier of China), the Ayatollah Khomeini, and Pope John Paul II. Ronald Reagan would join this crew with his election in 1981. Caryl contends that all of these figures, in their very different ways pushed the world in the direction of a common goal:

The counterrevolutionaries of 1979 attacked what had been the era’s most deeply held belief: the faith in a “progressive” vision of an attainable political order that would be perfectly rational, egalitarian, and just. The collapse of the European empires after World War I and the Russian Revolution, the Great Depression, and the triumph of wartime bureaucracy and planning during World War II all gave forward thrust to this vision; postwar decolonization and the rapid spread of Marxist regimes around the world amplified it. By the 1970s, however, disillusionment had begun to set in, with a growing sense in many countries that heartless (and in some cases violent) elites had tried to impose a false, mechanistic vision on their countries, running roughshod over traditional sensibilities, beliefs, and freedoms. As a result of the late 1970s revolt, we live today in a world defined by pragmatic and traditional values rather than utopian ones.

For three decades we have lived in this world where the utopian imagination has been expelled from the intellectual field. For my money, the question is: do we still live in this world?

We might answer this question by looking at the current state of the counter-revolutions of 1979. The Thatcher-Reagan revolution that pushed the idea of a less regulated market based society seems to have hit a wall with the 2008 financial crisis. Even before then, the idea that unleashing market forces would result in a general prosperity, rather than serve to heighten economic inequality, was already in doubt. A Romney-Ryan victory in the elections might give these ideas a new lease on life, for a time, but their administration is unlikely to solve the problems at the root of the current crisis because their philosophy itself was born out of a distinct set of economic and social problems that either no longer exist or are not the real problem: runaway inflation, the stranglehold of powerful unions, stifling regulation of the financial markets, welfare dependency. (It should be added that a continued Obama-Biden administration has no real solutions to our current problems either.)

It also seems quite clear that the capitalist revolution begun by Deng Zhou Ping in China seems to have played itself out. China is facing daunting demographic, environmental, political and socio-economic challenges that undermine its model of export led growth and one-party dictatorship. China cannot continue its rate of blistering growth because its disastrous one-child-policy has resulted in a society “that may grow old before it becomes rich”, even the slower growth it has been experiencing of late may be too fast for its fragile environment to sustain. The one-party dictatorship rather than representing the rule of wise, red-robed mandarins is rot-through with corruption and increasingly incapable of rational decisions- China builds bullet trains, but fails to build the practical infrastructure of a city like Beijing, so that the city experiences dangerous floods in which hundreds are killed.

Post-Khomeini Iran is a basket case in terms of its economy. It is unable to engage in needed reforms- as witnessed when it crushed the Green Revolution, and though it might have gained a huge strategic windfall with the American’s foolish overthrow of Iran’s worse enemy- Saddam Hussein’s Iraq- it has seeming squandered these gains. It has squandered the goodwill of the Arab populace in the wider region by supporting its murderous ally in Syria, and by obstinately pursuing the technology for atomic weaponry which alienates Arab governments, has resulted in the US strangling the country economically, and may result in an actual attack by Israeli or US forces- or both, which will further set back this great and historic people.

Lastly, the Catholic Church which saw the charismatic John Paul II succeeded by the papal bureaucrat of Pope Benedict, has seen its moral authority eroded by its secretive response to the tragedy of child sexual abuse by its clergy. The very conservatism that

served the Church so well when it fought against communism threatens now to not so much destroy the Church as radically shrink it. Rather than focus its energies on the real problem of rapidly disappearing numbers of priests, which might be solved by embracing women, and/or allowing priest to marry, it rewrites the liturgy to make it more historically authentic. American Bishops even goes so far as to threaten Church members who do not fully embrace politically all of the Church’s thinking with “soft-excommunication” in the form of being banned from receiving communion.

A good case can be therefore be made that the anti-utopian counter-revolution begun in 1979, is in many respects, a spent force.

There are ways in which the critical observations of late 19th century society offered up by Bellamy in Looking Backward eerily resemble the problems of our own day. The novel begins with the narrator lamenting the sad state of the relations between labor and capital.

Strikes had become so common at that period that people had ceased to inquire into their particular grounds In one department of industry or another they had been nearly incessant ever since the great business crisis of 1873. In fact it had come to be the exceptional thing to see any class of laborers pursue their avocation steadily for more than a few months at a time.

What we did see was that industrially the country was in a very queer way. The relation between the workingman and the employer between labor and capital appeared in some unaccountable manner to have become dislocated. The working classes had quite suddenly and very generally become infected with a profound discontent with their condition and an idea that it could be greatly bettered if they only knew how to go about it On every side with one accord they preferred demands for higher pay shorter hours better dwellings better educational advantages and a share in the refinements and luxuries of life demands which it was impossible to see the way to granting unless the world were to become a great deal richer than it then was. (LB-19-21)

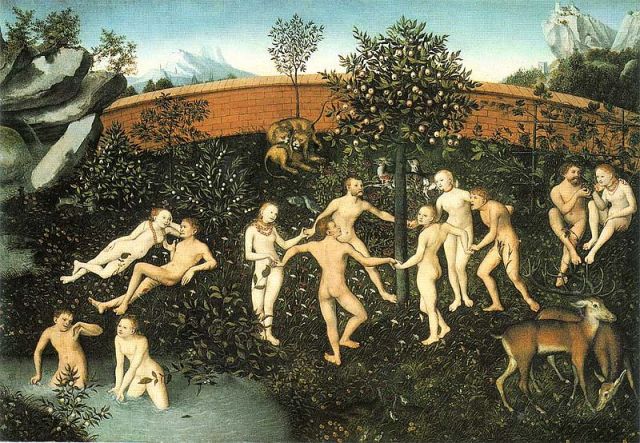

Bellamy describes the relationship between the minority of the rich and the majority of the poor in the 1880s as that of the rich seated in a coach being pulled by an army of the poor.

The driver was hunger and permitted no lagging though the pace was necessarily very slow. Despite the difficulty of drawing the coach at all along so hard a road the top was covered with passengers who never got down even at the steepest ascents.

Naturally such places were in great demand and the competition for them was keen everyone seeking as the first end in life to secure a seat on the coach for himself and to leave it to his child after him. (LB 11-12)

How did the rich feel about the condition of the poor?

Was not their very luxury intolerable to them by comparison with the of their brothers and sisters in the harness the knowledge that their own weight added their toil? Had they no compassion for beings from whom fortune only them? Oh yes commiseration was expressed by those who rode for those had to pull the coach especially when vehicle came to a bad place in the road it was constantly doing or to a steep hill.

It was agreed that it was a great pity that the coach should be so hard to pull and there was a sense of general relief when the specially bad piece of road was gotten over This relief was not indeed wholly on account of the team for there was always some danger at these bad places of a general overturn in which all would lose their seats.

It must in truth be admitted that the main effect of the spectacle of the misery of the toilers at the rope was to enhance the passengers sense of the value of their seats upon the coach and to cause them to hold on to them more desperately than before. If the passengers could only have felt assured that neither they nor their friends would ever fall from the top it is probable that beyond contributing to the funds for liniments and bandages they would have troubled themselves extremely little about those who dragged the coach. (LB 13-15).

The financial panic of 1873 and the economic depression that followed, the conditions which inspired Bellamy to write Looking Backward, have been replaced in our imagination by the Great Depression of the 1930s. Aside from economic historians, few people probably even known that there was a collapse of financial markets in the 1870s ,or that it was followed by a period of very slow growth that saw acute struggles between capital and labor for society’s diminishing returns. This lack of historical knowledge is sad because it blinds us to the historical scenario that is perhaps the best analogy to our own. Whereas the Great Depression saw a financial crisis followed by severe unemployment, the Long Depression began with a financial crisis in 1873 and was followed by a generation of mass underemployment and deflation. This point that 1873 and its aftermath are the better analogy to our own day has been made by many economists-including Paul Krugman.

The times, therefore, might be ripe for an upsurge in utopian imagination, a utopianism conscious of its own colossal failures and the crimes committed in its name.

Looking Backward: 2100-2012, anyone?