If as mentioned previously the First Opium War opened China to British drug pushers, it also opened up China to the cultural influence of the West, and one of these influences stemmed from the flood of Christian missionaries who thereafter inundated the country.Obviously there was a lot lost in translation between these Christian missionaries and the Chinese, for after Hong Xiuquan, a member of the Hakka ethnic group in southern China, encountered Christianity he became convinced that he was the brother of Jesus who had been sent to China to rid the country of “devils”.

The devils Hong Xiuquan was talking about included the Confucian meritocracy, themselves the heirs of a practical variant of utopianism. This resentment towards Confucians was not surprising given that he had failed the civil service exams, based on the Confucian classics numerous time, and thus found himself barred from a government post that would have granted him a stable income and place in society.

This is one of the stupendous what-ifs of history, like Hitler not getting into art school in Vienna, and going on to almost destroy Europe. Would the Taiping Rebellion have never happened, would 20-30 million people not be killed if one man was better at taking standardized tests? Can the gods be so cruel in their irony?

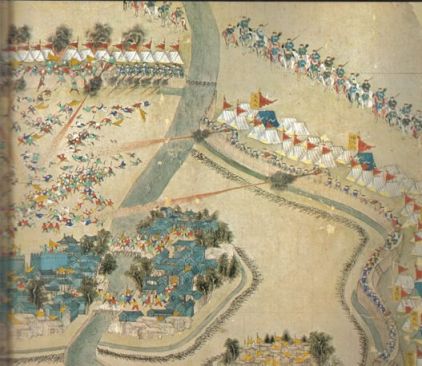

As it was, Hong Xiuquan set to preaching and soon had himself a sect. In part, the attraction of the sect was a reflection of the dystopian environment around him. Bandits robbed seemingly at will, the Hakka people fought incessantly over sparsequality farmland, natural disasters rocked the country . The civil and population pressures gave rise to a pernicious practice of female infanticide that overtime caused the natural ratio of males to females to become all out of whack. Young hot-bloods had too much testosterone in their veins and too little food in their stomachs, and were thus a volatile mix in which Hong Xiuquan served as a match. Much of the popularity of the Taiping movement, like the modern day Taliban, stemmed from their ability to bring a semblance of order and security to this otherwise chaotic and dangerous world .

Yet the the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, established in modern day Nanjing, was something much different than the Taliban. It was a strange hybrid form of utopia, a kind of marriage between what we in the West would understand as Puritanism, abolitionism, feminism, Spartan or pseudo-totalitarian military organization, and perhaps even a version of Malthusian environmentalism.

The Taiping replaced the Confucian classic that had served as the gateway to government office with the Bible, vice laws were passed and came down hard on opium users, gamblers, consumers of alcohol, and prostitutes. The sexes were strictly separated, and, in one of those classic examples of utopian overreach, sex, even by married couples, was discouraged.

At the same time, the Taiping launched a program of radical egalitarianism that gave the rebellion characteristics somewhere between the French Revolution and the American Civil War. In a stroke, they abolished private property, banned the barbaric practice of foot- binding women, and declared the sexes equal, permitting women to take exams and serve in government. They also, before the Emancipation Proclamation was even conceived, abolished slavery (of the Chinese variety).

It was their tight military structure and totalitarian organization of society that made the Taiping so hard to defeat. They proved as effective at mobilizing society as the civic-republicanism of the French people mobilized against Europe only a few decades before. The degenerating Qing Dynasty that ostensibly ruled China had a much harder time putting down the Taiping separatist than the Union armies had bringing down the Confederacy almost simultaneously. And unlike with the American war, the British took sides in the conflict and supported the Qing, which may have been a decisive element in their eventual victory.

Many of the policies of the Taping Heavenly Kingdom might be understood as utilitarian responses to a Malthusian environment. Their prohibitions on sex were efforts to drive the population down, and sexual equality offered an answer to the distortions of female infanticide. Women in the kingdom were just as valued as men.

This weird mash-up of different, and contradictory, forms of utopia to Western eyes seems not to make sense. Yet, when seen from the perspective of what was happening elsewhere in the first half of the 19th century, the strangeness of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom becomes less bewildering.

The Taiping Rebellion occurs in the historical space between the French Revolution and American Civil War and contains aspects of both. Perhaps revolutionary concepts blew like pollen across the Central Asia and the Pacific and cross-fertilized with native Chinese elements to create the strange hybrid of the Taiping Heavenly kingdom.

What the French Revolution, American Civil War and Taiping Rebellion all shared is that they were attempts to create what we now understand to be a modern, sovereign state. What the founding fathers of modern China, Sun Yat Sen and Mao saw in the Taiping utopia was a hopeful harbinger of this new form of the state in China, and therefore, despite their differences in vision from it, admired the rebellion as a failed attempt at necessary transformation.

The current plutocrats ruling China, however, see in the Taiping a dangerous historical precedent that must be guarded against at all costs. What was once the source of partially irrational utopian hopes of the Chinese leadership has become the source of equally irrational dystopian fears. Anyone wondering today about China’s often cruel and seemingly paranoid treatment of Christians, Tibetans, or fringe religious sects such as the Falun Gong needs to keep the historical experience of the Taiping Rebellion in mind in order to understand the root of Chinese fears.

What relevance does any of this have today? Some have suggested that we keep the experience of the Taiping Rebellion at the forefront of our minds when we think any future large scale disruptions to Chinese society. One might wonder out-loud how China is going to deal with its massive demographic, environmental and political challenges. One might also wonder how China, now the “workshop of the world”, like the British who cleaned their clock in the Opium Wars, might deal with another tectonic shift coming from automation and localized production that challenges that status.

Given how purely speculative all this is, what interests me most is what kinds of strange cross-fertilizations, like that between the Taiping Rebellion and intellectual flora that originated in the West, are going on today, and, more important may occur in the near future.

As I wrote in a recent post, it might be a good idea for people in the West to start looking for novel ideas about politics, culture, technology, art to start emerging from the more dynamic developing world, and that would include China, even though it is rapidly aging and therefore probably missing something of the natural utopianism and innovation of youth.

When the history of the Occupy Wall Street Movement is written one of its most interesting aspects might be that it was inspired by a similar movement in the developing world- the Arab Spring. (Though it might be more accurately called a Mediterranean Spring and have its origin in Greece). One can only imagine, should China ever bloom into its own spring, what strange and interesting ways of thinking and being in the world might emerge there. What bloomed in China might eventually make its way to our shores to combine with Western traditions giving rise to something we have not seen before, perhaps for ill, but let us hope, for good.