THE QUANTS

Quants is a term for a breed of mathematical wizards who, from the early 1970s forward, essentially built the computerized system of finance we have today. Before the quants, Wall Street types were largely made up of testosterone filled, play- by- the- gut traders- (think Gordon Gekko of the 80s classic- Wall Street- though no doubt with harrier knuckles than Michael Douglas.) After the quants, Wall Street would be filled with refugees from the world of quantum physics or other math heavy branches of the sciences. Its myriad of financial transactions would be no longer be based on the gut instinct of human traders, but run by advanced algorithms that churned away the world’s daily business within a bewilderingly complex network tied together through satellites and fiber optic cables that literally circled the globe. The world for the first time had truly become “one world” with everything of value in it symbolized in electric strings of ones and zeros.

How did this come to be so?

A book probably destined to become the definitive story of the rise of the quants is the Wall Street Journal’s Scott Patterson’s The Quants: How a new breed of math whizzes conquered Wall Street and nearly destroyed it. Patterson begins his story with Ed Thorp, who started his career not as a Wall Street trader, but as an academic with a penchant for gambling.

The journey to quantdom began with the quest to beat the roulette wheel. Thorp was sure he could figure out a “scientific system” to predict where the ball would fall, and thus conquer chance and make himself a fortune. He found an unlikely ally in the economist, and gagater, Claude Shannon.

In a scene that reminded me of the 60s classic Get Smart, Patterson recounts how Thorp and Shannon invented a roulette computing computer that was placed in Shannon’s shoe. Shannon would relay the predictions to the roulette playing Thorp through a radio device in his ear. The scheme, of course, went nowhere, and could have ended up getting the both of them killed. Thorp, however was not to be deterred, chance could be beaten, even if it wasn’t the chance of the roulette wheel. He turned his attention to BlackJack, where he did, indeed, come up with a winning strategy that he would turn into a best selling book- Beat the Dealer. With one kind of chance beaten, Thorp set out to conquer another, and he set his eyes on the biggest casino in the world, the one found on Wall Street. Thorp’s core method, as it would be for all quants, would be to use advanced computers, and highly sophisticated mathematics borrowed from the physical sciences, to divine the future of the market, the outcome of the great financial game, and in the process make a killing for himself.

Thorp, who with philosophy major, Jay Regan, started the computer based trading firm Thorp and Regan, was but the first of a flood of people with an advanced mathematical background who would stream into Wall Street, especially after the 1980s, enabled by financial deregulation, the explosion of super-fast and relatively inexpensive computing, and the development of sophisticated mathematical finance.

Thorp’s quant brethren, a good deal of whom also had a taste for gambling included: Ken Griffin (Citadel Investment Group), Cliff Asness (AQR Capital Management), Boaz Weinstein (Deutsche Bank), and Jim Simons, who emerged from the super-secret field of military cryptography to create what is perhaps the most successful quant fund in the world (Renaissance Capital Management).

I should step aside from Patterson’s narrative for a moment and provide a general picture of the historical circumstances that coincided with the rise of the quants. The quants were just one of many groups linked together by newfound faith in “the market” that had emerged from the failure of Keynesian economics. To overly simplify the matter, Keynesianism, which had grown out of the collapse of the global economy in the 1930s, held the position that government managers should interfere with the economy to prevent a rerun of the Great Depression, and perhaps more importantly, believed that such interference with the economy would work. This interference was largely what is called “counter-cyclical”. When recession struck the government would run up huge budget deficits to keep unemployment from going so high that it would derail consumer spending, thus, in theory, avoiding the vicious circle of unemployment-less spending-more unemployment that had characterized the Great Depression.

By the 1970s, Keynesianism was a spent force. Yes, another Great Depression hadn’t occurred, but Western economies became mired in unemployment and seemingly intractable inflation as this great sketch by comedian Father Guido Sarducci illustrates better than any economist could.

The revolution that Ronald Reagan (though Reagan with his oversized budget deficits was perhaps more of a Keynesian than some would admit) and Margaret Thatcher launched in the early 1980s would assert not only that markets were smarter than any government manager, but that giving the freest reign possible to the markets would eventually lead to prosperity for all.

The argument between those who favored some sort of government management of the economy, and the proponents of the wisdom of the markets, was at root an epistemological argument- an argument over how knowledge worked. The Keynesians might have argued that if an economy was to avoid the kinds of crises experienced in the 1930’s you needed able management at the top, an expert who kept the ship on course. The position of the market proponents was that knowledge was best processed from the bottom up, as individuals made decisions based on their interactions with one another. Based on these interactions, the sum of all individual interactions- the market- was an order of magnitude smarter than any individual bureaucrat who by necessity had to understand the economy on an abstract level, and thereby risked losing so much of the economy’s actual detail that they lost touch with reality itself.

To return to Patterson’s narrative, the strange thing about the quants is that they were both true believers in the free market, who simultaneously held that they were so smart that they could “beat the market”-the title of one of Thorp’s books. This idea that the market could be outsmarted flew in the face of the prevailing theory of how markets worked, the so-called, Efficient Market Hypothesis. The idea behind the EMH was that markets were always smarter than any individual or subgroup because markets reflected the total of information exchanged between individuals. If you own what is called an “Index Fund”, through your 401K at work, or for some other reason, your retirement future is built on the assumption of the EMH. That is, an Index Fund buys an entire market assuming that there is no way for human beings to be able to pick winners and losers- the hope being that winners out number losers over the long haul.

Quants certainly believed in the wisdom of the market. They even had a word for it “Alpha”, the website Seeking Alpha, and the hedge fund magazine Alpha get their name here. What the quants believed was not that the market was wrong, but that it was slow. If, through their sophisticated mathematical models and lightning fast computers, they could get to the “Truth” first- say by buying up a stock that their models told them was about to rise in price- they could make a killing. And many of them did just that.

Here’s Patterson on the quest for Truth of the quants:

The Truth was a universal secret about the way the market worked that could only be discovered through mathematics. Revealed through studies of obscure patterns in the market, the Truth was the key to unlocking billions in profits. The quants built gigantic machines- turbocharged computers linked to financial markets around the globe- to search for the Truth, and to deploy it in their quest to make untold fortunes. The bigger the machine, the more Truth they knew, the more they could bet. And from that, they reasoned, the richer they would be. (The Quants, p. 8)

The quants, using their sophisticated mathematics were largely responsible for the creation of a whole host of financial exotica, such as Credit Default Swaps, that came to the public’s attention with the financial collapse of 2008. Many of their creations were meant to hedge risks, thereby “guaranteeing” profit, and became a large component of the delusion that human beings had gotten so smart that full-blown financial crises were a thing of the past. Economists called this lack of crises, what proved to be a mere calm before the storm “The Great Moderation”- a delusion that was believed in all the way up to Federal Reserve Chairman, Alan Greenspan himself. Once the valuation models the quants had devised to price their exotic financial instruments was shown to be an illusion, the financial institutions that held them started to unravel. As the financial system verged on the edge of collapse in 2008, the quants models, which predicted that the market would soon return to equilibrium, stopped working. Panicked investors were not acting as the model of human beings as rational actors would suggest. Quant funds were forced to join in the massive selling, or risk being wiped out entirely, as the value of not just the exotic instruments they invented, but the market itself, evaporated in the biggest decline since the 1930s.

There had been lone prophets who tried to point out the fundamental errors in the models of the quants. One of these prophets was the mathematical genius Benoît Mandelbrot who, way back in the 1960s, observed that many markets rather than reflecting the smooth structure one would expect from a phenomenon of rational actors looking for the best price, was instead filled will all of these crazy spikes as prices alternatively soared then crashed. A more contemporary critic of the quants was the trader and writer, Nassim Taleb, who pointed out that the mathematical models of the quants, which were based on the physical sciences where predictable averages- Gaussian bell curves- were the order of the day (say the average human height- Mediocristan) did not work in the realm of economics because it was prone to extremes (say a sample of average income with Bill Gates in the mix-Extremistan).

The cries of the prophets were for-not until the whole system reached a point of near implosion. An implosion that was only halted by a massive Keynesian intervention and reinflation in the form of bailouts and stimulus aimed largely at the financial sector, but also elsewhere (GM) by the world’s most powerful governments and their central banks. An action that almost certainly lacked much, if any, democratic legitimacy, and that, while probably having saved us from a full-scale implosion of the global economy, has not allowed us to escape what is proving to be a long“soft-depression”. Indeed, if the current crisis in the EU portends the future, governments may have merely postponed an economic reckoning that will likely now be centered on the bloated finances of the governments of the rich countries rather than the financial markets themselves.

This may seem like a particularly long and drawn out detour from what I had promised in the post preceding this one, that is, to apply what I had learned from David Hawkes’ reading of Paradise Lost to the quants. So, without further ado, let’s see where this takes us:

I should say right off the bat that what I am about to do is apply religious concepts to secular phenomenon. This might strike some as vulgar and a debasement of spiritual concerns. I understand this concern, and think it real myself, but nevertheless find this effort worthwhile. My suspicion is that when we peer underneath things we today believe to be wholly secular, we will find ideas that have their origins in religion. The reason we likely don’t recognize this is that ours is the first truly secular age, that is, it is the first age whose social conventions are devoid of any explicitly religious context, or, in other words all other ages have approached both the human and the natural world through religious ideas. It is from this realization, not from any sense of my own personal religion or spirituality (I have little of either) that I think approaching the world using religious concepts is sometimes helpful, and this is the case even if the current religions are no more “real” than the religion of the Greek gods.

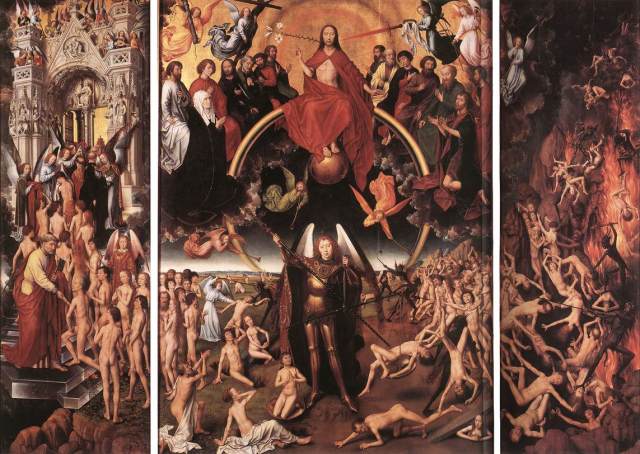

To continue: It would be a mistake, I think, to believe the quants were brought low by the vice of greed alone, and Milton/Hawkes can perhaps help us see why. The broken relationship (sin) that underlies the whole of Paradise Lost is the sin of idolatry, and for our purposes, one can see this most especially in the construction of the capital of Hell, Pandemonium. The fallen angel Mammon (again meaning money) whose vision becomes the basis for Pandemonium was, while he was still in Heaven, transfixed by its beauteous gold. Mammon confuses this mere symbol of Heaven’s beauty for the beauty of Heaven itself. If its golden visages could be duplicated, in the logic of Mammon, then the fallen could recreate Heaven in what was actually Hell. It is this confusion, of the power brought to us by money, Milton seems to be telling us, with the powers of Heaven and of God, which is the danger point of our relationship with earthly wealth, rather than the animal-like greed for more and more. Mammon’s Pandemonium, is perhaps, like the beautifully decorated Anglican (and before that Catholic) cathedrals that dotted England in Milton’s day, a confusion of style over substance, an affront to the idea of God as the source of charity and love.

Ultimately, this boils down to an argument over what we should attend to during this short life of ours. The quants were, without doubt, brilliant individuals. Yet, they chose to use this brilliance not to seek out cures for disease, or find ways to aid the poor, or even to unveil the beauty of creation through science, but sought the generation of riches for themselves, and wealth for the already well off members of the hedge funds they managed. (Hedge funds, by law are limited to people with a minimum of a million dollars in assets).

The quants might respond that the wealth they were chasing would eventually make its way down to the lower classes like manna from Heaven. It would be a difficult argument for the quants to make in regards to the poor, given how hard the financial crisis, in part caused by the quants, has been on the least well off. It would be just as difficult a case for the quants to make for the middle class whose imaginary wealth- the value of their houses and stocks- disappeared as quickly as the electrons it was made of, once the power of cheap borrowing, of leverage, short- circuited.

It is not merely, however, the fact that the quants could be accused of idolatry in the sense of their worship of wealth, of which many could be accused, but that they were guilty of idolatry in that they both exalted their own idea of “truth” in a way that was almost quasi-religious, and that they practiced what was in a sense a form of divination.

On the first point: the mathematically inclined seem almost cognetally prone to a form of Platonism. That is, they tend to look at numbers not as mundane symbols to be manipulated for our purposes, but as part of some sort of higher reality whose truth stands above all human convention. You get this weird faith in the ability of numbers to capture reality in the most practical of people, “show me the numbers”, means the same thing as show me the truth, a phrase whose underlying assumption is that the truth can best be captured by abstract digits.

For the quants, “Alpha” was not some limited model of the financial world, but the deep, underlying truth of the it. Alpha was not a symbolic representation of the market, but was the market itself. The fact that this idea was neither rational, nor pragmatic, but instead constituted a sort of faith, can be seen in the fact that the quants’ belief in Alpha was not subject to doubt. Critics, such as Benoît Mandelbrot, or Nassim Taleb weren’t really engaged or answered, they were brushed aside because they didn’t conform to this “faith”. In an earlier age, such heretics might have been burned at the stake, but in our humane present, they were subject to the intellectual equivalent- they were ignored. This blind faith was only called into question by the quants when their “god” failed them and their models were shattered by the hammer blows of reality.

On the second point, I don’t think it is surprising that many of the quants started as gamblers, and not just because Wall Street is the greatest casino on earth, which it certainly is. Rather, gambling has a deep relationship with divination, and what the quants were really trying to do was peer into the non-existent future in order, as all divination does, to assert control over the existent present.

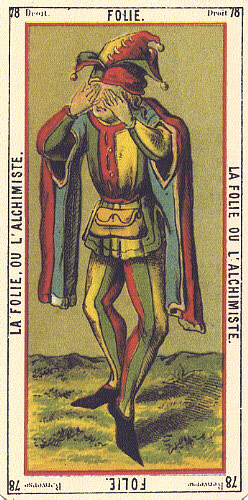

It’s a chicken-and-egg- question of whether gambling or divination came first in human history, and for all intents and purposes, it seems the further we go back the more indistinguishable the two probably become. The fact that a person’s future could be predicted using cards- the modern version of this is, of course, the Tarot deck, or dice, makes perfect sense if we put ourselves into an idolatrous frame of mind- which is essentially the frame of mind of almost all pre-scientific forms of thinking. The key mistake of idolatry is to confuse the symbol with the symbolized. This mistake seems to naturally imply that the more “like” the actual thing our symbol for something is, the more it actually is the thing being represented. An individual life is subject to chance, therefore, if we know the outcome of a game of chance we will be able to predict what will happen in an individual life.

The quants did almost precisely this with their models. What they did is construct extremely sophisticated chance games with one caveat: that the outcome of the chance games would trend towards the equilibrium of the Efficient Market Hypothesis. Like a fortune teller they played their Tarot decks, and then confused the outcome of these games with the economy the rest of us make our living in. Perhaps like the gut-level traders they replaced, and like the successful fortune teller, much of their initial luck arose as much from their intuition as their models. Perhaps, too, like the successful fortune teller, many of them were supremely good con-men who were quick to recognize and exploit the vulnerabilities of people who believed in their predictive power.

This world the quants had helped create only became supremely dangerous for the rest of us when the gap between their models and reality became too wide, or worse was ignored. The fall of idols is always difficult to bear, and given the fact that the larger economy had become tied up in the belief in these false models, their being proven false couldn’t help but affect the vast majority of us who had never heard of a quant or a hedge fund or, or algo-trading, or a credit default swap.

The markets were only saved when the public and quasi-public institutions, the world’s most powerful governments and central banks- (the latter, which especially, had up to that point, been the most vociferous proponents of the virtues of the free market) both turned tail and “got Keynesianism” flooding the markets with cheap cash. This magical elixir to cure the burdens of debt, however, was one limited to the richest institutions and elements of society. Financial deregulation and the exotic instruments devised by the quants had turned the creditors into their own debtors, and these debtors would be cured by the magic of cheap money, a concoction brewed by the world’s central banks who had previously treated even the hint of cheap money like poison.

Something seems to be seriously wrong with our financial system, something that reaches back long before the quants, and touches upon the fundamental assumptions behind the seemingly oldest elements of our economic life- money and debt. Which leads me to the last question along this train of thought:

How might something seemingly so essential to our lives as economic creatures, our money and our debt, be viewed through the lens of idolatry?

Until next time…