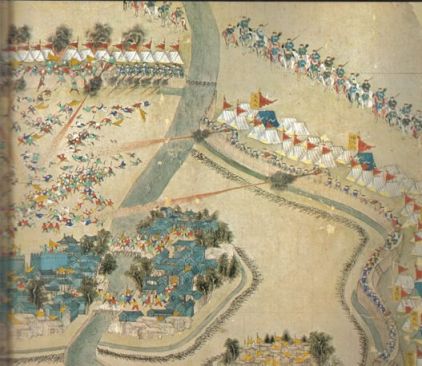

Around the same time as the American Civil War a civil war that became known as the Taiping Rebellion was raging in China. The American Civil War was a brutal conflict that left 625,000 Americans dead. The Taiping Rebellion resulted in the deaths of somewhere between 20-30 million people, making it one of the bloodiest conflicts in human history.

The origins of the Taiping Rebellion lay some years prior in the First Opium Wars fought between the British and the Qing Empire of China from 1839-1842. In the Opium Wars the grand old British Empire played the role of the modern day Columbian drug cartel,

or Mexican drug lords, with the major difference being that the British, being militarily superior to the Chinese, were able to force China to accept the British importation of an addictive poison rather than just sneak it across the border.

As a consequence of the devastating impact of the opium trade on the people of China, the Chinese Emperor sent the Confucian scholar Lin Zexu to the port of Canton in order to put a stop to the importation of the drug by British merchants. Lin wrote an impassioned letter to Queen Victoria appealing to her sense of humanity with the hope of stopping the trade.

We find that your country is distant from us about sixty or seventy thousand miles, that your foreign ships come hither striving the one with the other for our trade, and for the simple reason of their strong desire to reap a profit. Now, out of the wealth of our Inner Land, if we take a part to bestow upon foreigners from afar, it follows, that the immense wealth which the said foreigners amass, ought properly speaking to be portion of our own native Chinese people. By what principle of reason then, should these foreigners send in return a poisonous drug, which involves in destruction those very natives of China? Without meaning to say that the foreigners harbor such destructive intentions in their hearts, we yet positively assert that from their inordinate thirst after gain, they are perfectly careless about the injuries they inflict upon us! And such being the case, we should like to ask what has become of that conscience which heaven has implanted in the breasts of all men?

The result of Lin’s efforts was a war by the British against the Chinese Empire, that the Chinese were destined to lose.

The fact that tiny Great Britain, with a little over 27 million people in 1850, could so easily have brought a continental empire of 450 million to heel would have been considered ludicrous only 50 years before. It was certainly the case that European powers had had an easy time knocking off the great empires of the Americas- the Aztec and the Inca- two centuries earlier, but these were civilizations lacking steel, wheels, horses, or gunpowder weapons, technologies the Europeans had largely imported from fellow Old World civilizations- especially the Chinese. As Jared Diamond has pointed out, the Europeans were also in possession of devastating weapons of mass destruction in the form of diseases to which Native Americans had no immunity, and which killed more than any of the cruelties of conquest.

China, though, should have been different. China was the oldest living civilization, the great technological, political and cultural innovator. It was, after all, the more advanced society Europeans were trying to get to in search of trade, technology, and a hoped for ally against the Muslims when Columbus “goofed up” and ran into the New World.

The reason China wasn’t different is that the world had begun one of those great periods of tectonic shift in nature and history. This time, the shift was the development of a whole new type of civilization, an industrial civilization which, for a time, turned the Western civilization in which it first took root into the ruler of the world. For the mechanized British army and navy the “white man’s burden” that came with technological advantage meant cornering the Chinese drug market, and crippling the world’s most revered civilization.

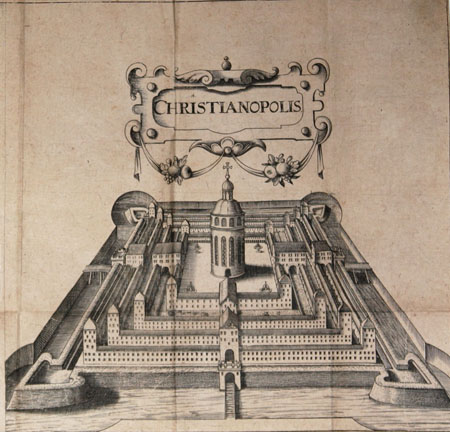

The response of some of the Chinese to all this was the establishment of a pseudo-Christian utopia called the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. The war between the Qing Chinese and this strange utopian-cult would constitute the bloodiest conflict of the 19th century rivaling the wars unleashed by the ravenous Napoleon…